For Australia, Anzac Day is a national day. For New Zealand, where conscription removed individual choice, it is more a day of remembrance.

Attitudes change, of course. New Zealand Anzac Days are now better attended and we sometimes even hear debate about whether Waitangi or Anzac Day is our ''real'' national day. And I suspect Brits and Yanks, sporting their decorations on November 11, still wonder why Armistice Day/Remembrance Day passes so quietly in Australasia.

But why do we commemorate World War 1 (and subsequent conflicts) in April rather than November?

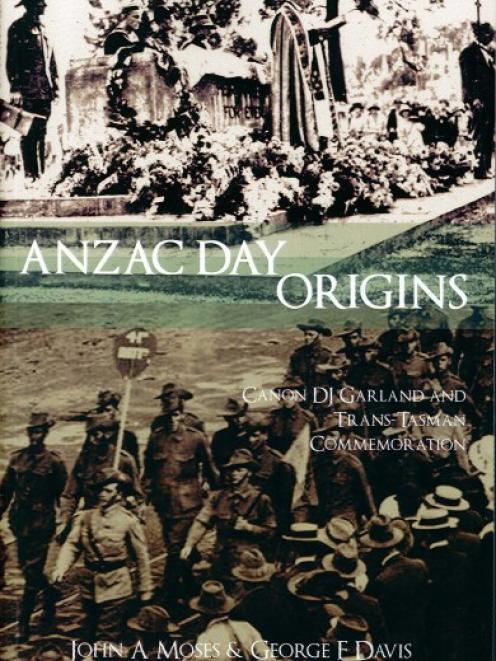

Anzac Origins, a collaboration between Australian academic the Rev John Moses and Dunedin PhD graduate George Davis, examines public reaction to the Gallipoli campaign and, in particular, the campaign of Queenslander Canon David Garland to have Anzac Day set aside as a day of solemn commemoration.

The expression ''holy day rather than a holiday'' recurs in places. Barton Books' website shows it is a religious publisher. The first page of the foreword deprecates the ''barrage of assertion from newly proselytising fundamentalist atheists'' and the authors sometimes come across as testy in their criticism of ''nationalist'', ''leftist'' and ''feminist'' writers they consider challenging ''the Anzac myth'' (their quotation marks).

At one point, discussing the case for making Anzac Day as a close or sacred public holiday, they argue that ''those historians whose secular formation precludes them from entering into and comprehending the spirituality of Christians, and in particular of chaplains, are permanently hindered from getting to the heart of the matter''.

But even if you disagree with their conservatism, Moses and Davis' research and energy cannot be faulted. The book draws on a considerable range of primary and secondary sources, is fully end noted and is well indexed.

Anzac Origins is driven by Moses' interest in Queensland Anglican David Garland, who spent time in New Zealand as well as his own dominion. Davis supplies a New Zealand angle.

They begin by looking at issues such as war and English theology and the German threat to the respective nations before looking at Garland's work. It was easier here, with just one national government to convince, rather than a central government and several state ones.

There were many debates about the timing and content of the day's commemorations. We now rush off to the mall sales in the afternoon but, 80-90 years ago, the big issue was horse-racing.

Garland and the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee of Brisbane generally set the tone for the day's observances here and across the Ditch and influenced both countries' Anzac Day legislation, arguing that New Zealand MPs' language ''and the constant reiteration of the word `sacred' had little else on their minds than a sacred day in terms of those times''.

There are a few slips. Few historians would contend that New Zealand's change from colony to dominion in 1907 was very important. The pre-dreadnought HMS New Zealand was not dominion-supplied. James Allen was defence minister in the Massey Government, not the Stout one. And our gift warship, the second HMS New Zealand, was a battlecruiser, not a cruiser.

That aside, Anzac Day Origins provides an interesting and firmly argued examination of a day that can get only busier as we formally commemorate World War 1.

Gavin McLean is a Wellington historian.