Trifecta, Ian Wedde's eighth novel, contains one trifecta in the traditional betting sense: Michael (Mick) Klepka at his local TAB puts ''five grand on a Final Touch, Xanadu and Burgundy trifecta on the Trentham Telegraph'' on the last day of his life.

But poet laureate Wedde, a man who wears many hats besides that of the novelist, is not one to be satisfied with a single literal meaning.

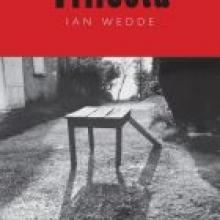

The cover, Bill Culbert's 1982 photograph, Table Leg, an image from the collection at Te Papa Tongarewa, with which Wedde was long associated wearing a different hat, depicts a table with three surviving legs propped up at one corner by a longer chunk of wood at an angle.

It might be read as a found metaphor for the Klepka family, made up of Mick and his two siblings, propped up by Martin Klepka, their famous father, dead for more than 40 years but still a factor in their lives through his architectural masterpiece, the Red House, in which Mick lives and which his sister, Veronica (Vero), and his brother, Alistair (Sandy), want him to vacate so they can sell it and claim their shares of the sale money.

They might be seen as Martin's trifecta in the contemporary sense of ''any threesome of significant actions or achievements'', carrying on his name (echoing that of Ernst Plishke, the Austrian refugee designer and architect who brought Bauhaus Modernism to Wellington) and carrying memories of him, not always flattering.

If the Klepka siblings can be viewed as their father's trifecta they might also be viewed as Wedde's.

He has said on the Victoria University Press website These Rough Notes that he had been thinking of ''writing a series of linked stories in which distinct voices and points of view would intersect'' and that for such a structure ''three is the ideal relationship number (''sad'', ''bad'', and ''mad''), referring to the three major headings under which personality disorders have popularly been discussed (which Vero uses in telling Sandy he has been the sad one, she the bad one, and Mick the mad one).

Wedde's trifecta triumph was to invent three siblings who shared the same eccentric, self-dramatising, dogmatic, egotistical, talented father and the Red House that represented him but who each reacted differently to create three distinctive personalities that could be described in the triad of ''disorders''.

To present his three characters Wedde focused on the stream of consciousness (in the present tense) of each on a single day in Wellington.

Mad Mick is seen as compulsively pleasure-seeking, driven, he believes, by his brain chemistry towards what ignites his pleasure centre.

The last day of his life sees him engaged in seeking out all his addictions: gambling, sex, alcohol, nicotine, a variety of illegal drugs, even chocolate.

He uses the Red House, which he has almost emptied out, as a place to sleep and to watch television while he imbibes his nightcap, a base from which he can move out to seek his pleasures at the TAB, the Sports Bar, the Honeysuckle massage parlour, and the street life of Wellington.

He is happy to hold on to the place also as a means of thwarting his siblings, for whose lifestyles he has no use.

He ends his day giving up on surfing TV for porn and old movies and watches his drug-induced hallucinations on the blank screen.

He is characterised not only by his activities but by his distinctive language, ranging from the jargon of horse-racing to the technical terms of brain chemistry, and by his vivid memories of his father playing a wittily cruel joke on Sandy, dropping dead in the middle of a typical exhibitionist performance while mowing the lawn wearing only his wife's apron.

Vero's self-description as the ''bad'' one is probably because of her most vivid recurring memory, her one-night stand with a German tourist in Venice 26 years earlier on the night that she later discovered her mother had died back in Wellington.

On the VUP blog Wedde describes her as one who believes in ''taking care'', with all the impossible contradictions involved in that.

We see her on the day after Mick's pleasure-filled day, when he has been discovered dead in front of the television set in the Red House, a day in which she, in Napier, possibly saves the life of a colleague who collapses on a power walk with her and others involved in the near-moribund Art Deco Heritage Tour company that she and her near-alcoholic husband badly manage.

Her language, very different from Mick's, is marked by what Wedde on the VUP blog describes as her ''richly synaesthetic world''.

She and Sandy spend the next day in Wellington handling the legal formalities and other issues raised by Mick's death, all seen from Sandy's point of view, in his distinctive inner language, marked by the formal and sometimes abstruse and often abstract language of the cultural studies on which he lectures at the University of Auckland, and by his compulsively recurrent memories of a sadly (to him) brief affair with a young German student eight years before, from which he dates the decline of his personal life and his academic career.

During that day he and Vero discover from a sealed codicil to their mother's will the existence an unacknowledged half-brother, fathered by their father on the cleaning lady, but more importantly, in their mutual confessions they discover more about each other.

Perhaps the ultimate trifecta accomplishment in the novel is the reader's reconstruction of the three siblings and their histories from the three streams of consciousness that Wedde has created, with no overt narrator to provide an ''objective'' perspective.

The novel in its 177 pages is not so long and complex as James Joyce's Ulysses (and is considerably funnier), but it offers similar challenges and satisfactions to the engaged reader.

• Lawrence Jones is an emeritus professor of English.