Watching Cap Bocage is like seeing yourself from behind for the first time.

The recently released documentary featuring New Caledonian environmentalist and independence activist Florent Eurisouke is simultaneously as foreign and familiar as that first unsettling glimpse of the back of your head in a mirror.

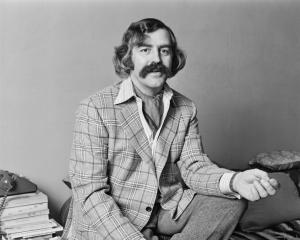

And holding the mirror is New Zealand film-maker Jim Marbrook.

''I was very aware a story like this would be a good one for Pacific people,'' Marbrook said.

''I think there are resource grabs going on all over the Pacific.''

Cap Bocage is named for a region on the east coast of New Caledonia's main island, Grande Terre. Home to indigenous Kanak people, the cape is dominated by a hilltop nickel mine operated by the Caldoche (New Caledonia-born French settler) Ballande family.

In January 2008, heavy rains caused a large mudslide of toxic sludge from the mine which polluted customary coastal fishing grounds.

Mr Eurisouke spearheaded a local protest demanding repair and restitution. But tensions grew between the protesters, Ballande employees, and those members of the community more inclined to accommodate the mine.

Mr Marbrook, a screen and television lecturer at Auckland University of Technology, was in the French territory at the time investigating another nickel mine when he heard ''something was happening up on the east coast''.

He soon decided to turn his lens on the cape.

''I'm interested in human stories,'' Mr Marbrook said.

''This film came from meeting a fascinating character and thinking he would be interesting to follow long-term.''

Filming took place in 2008 and 2010.

''The thread of the story became apparent in 2010,'' he said.

''In 2008, I knew I was filming an industry-community protest. Going back gave it more context and gave Florent's mission more context, too.''

Mr Marbrook, who learnt film-making in Montreal, Canada, was drawn to the French-speaking Pacific because of its proximity to New Zealand and its obscurity in Kiwi minds.

''I was very interested in media coverage of the French Pacific, and very aware that hardly anything filtered in to the English Pacific.

''I thought perhaps I could go there and see some stuff that I could connect with the English-speaking Pacific.''

A shortage of funds meant Cap Bocage was not completed until this year.

''I made a decision, when I went back in February, I was going to finish it this year no matter what and would just put it on the credit cards,'' he said.

''I felt it was relevant to a lot of things Pacific people are going through. And, by extension, what is going on here: mining on the West Coast and the Coromandel, the Rena still sitting on the reef, and ideas of mana whenua.

"Because one of the things it [the film] was about was sovereignty over the land in your backyard. Who owns what, and who can do what?''

It is estimated that a fifth of the world's nickel supplies are held in New Caledonia.

In 2018, the French territory is due to hold a referendum on independence.

Mr Marbrook's short film Jumbo was recognised at the 1999 NZ Film Awards.

He was director of the feature-length documentary Dark Horse which won Best Feature Documentary at the inaugural DOCNZ International documentary festival, in 2005.

A dramatisation of that story about bipolar chess champion Genesis Potini, starrring Cliff Curtis, and co-produced by Marbrook, has been released this week.