Tami Neilson, a two-time winner of the New Zealand ''Best Country Album'' award (Tui) and no stranger to the genre having grown up in a family steeped in string-band music, once recalled an essential songwriting tip passed from father to daughter:

''My dad and my brother are some of the best guitar players I've met in my life - and I've had the privilege to meet a few,'' the Canadian-born Auckland-based singer-songwriter said in an interview a few years back.

''But even though my dad can play every chord known to man, he used to always say to me, 'Tami, the simpler the better. If you can write a song with three chords or two chords ...'.''

Indeed, late American songwriter Harlan Howard, who provided words, music and inspiration to a long list of country music artists, including Patsy Cline, Waylon Jennings and Dolly Parton, once echoed an old refrain when asked what made a great country song: ''Three chords and the truth.''

With the New Zealand Gold Guitar Awards culminating in the senior finals at the Gore Town and Country Club tomorrow, it's timely, then, to explore that theme a little further.

And who better to ask than Delaney Davidson and Marlon Williams.

At Gore's St James Theatre on Thursday night, the Christchurch duo were declared winner of the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand's ''Best Country Album'' award (Tui) for Sad But True - the secret history of country music songwriting Vol 1 as well as the Apra ''Best Country Song'' award for Bloodletter.

Davidson, a 2012 ''Best Country Song'' finalist for You're A Loser, subscribes to the ''less is more'' approach to songwriting.

''The trick is to get the message across with as little distraction as possible and this is definitely true in the recording process,'' the musician explains.

''The ear or brain can only allocate so much space to new things. It's a balance of keeping up the interest and not overloading to the point where the listener is sated.

''Country music often deliberately keeps things small-scale. This personally engages the listener. As a style, it has definite terms and devices, which turn it into an attractive discipline.

''This is a really dry way to say it's best kept simple and direct. It has a tried and true form that still has endless possibilities. There are only so many stories to tell, but the variations are infinite.''

Williams, frontman of Christchurch act The Unfaithful Ways and a finalist for ''Best Country Song'' last year (for Ghost of This Town), agrees.

''Writing a complicated country song is like putting in a stained-glass window in a house looking out over Milford Sound; the more detailed the design, the more obfuscated the view of what was an otherwise beautifully honest picture.''

Describing Bloodletter as a ''morbid, tragic story swirling in ambiguous Platonisms'', Williams says it's best not to attempt to categorise a song as it is being written.

''As a listener I don't know what ticks a song over from a pop song to country song. And, as an artist, I think if you are considering that question then you're going about it the wrong way.''

Certainly, to categorise country songs as those falling within the parameters of ''simple and honest'' is to risk generalising a broad range of music, one that has roots that snake out into folk, blues, jazz, rock and pop (and their various sub-sets).

Adam McGrath, the burly frontman of The Eastern, another Christchurch act to make the final three of the Rianz ''Best Country Album'' award (banjo player Jess Shanks was also a finalist in the Apra ''Best Country Song'' award for her ballad Wait Out The Winter) says all forms of music can benefit from directness.

''We communicate better when we are concise and all good music works best when it reflects our humanness. The thing is, we get cocky in life; we `fussy' things up. The same thing happens in music.

''That's not to say intersecting poly-rhythms and discordant chord shapes can't be cool, but I've never heard anything as powerful as Woody Guthrie and one guitar,'' McGrath said.

''It ain't for me to define what is and what isn't anything. I believe in spirit and heart and guts and I want to find that in the tunes I love. I want to dance to songs that are played for the joy of playing.

''I want the soundtrack of my life to echo my life in a way, to filter the heartbreak, to shine light on our struggles and give rise to our best instincts: kindness, empathy, hope, justice and, most importantly, fun and love,'' McGrath said.

''I'm not someone who likes a lot of fluff and pomp. I see these bands carrying pedal boards on to stages that would shame an airplane's controls, and I wonder if without them they would actually have anything going on.

''You can have pride in a bare-knuckle approach. I want to know that our songs can stand on their own and do the job with or without the armour. Let's face it, wood has a resonance and a direct line to your heart that no computer file or circuit board could match.''

Fellow Rianz ''Best Country Album'' award finalist Donna Dean is wary of musical boxes even though she is no stranger to the awards ceremony, having twice won the country album Tui for What Am I Gonna Do? (2011) and Money (2004), and the Apra ''Best Country Song'' award for What Am I Gonna Do? (2011) and Work It Out (2004).

''People like to put a label to an artist's work. If I was pressed to give mine a handle, I'd say 'Americana' or 'roots' music because of its inclusion of so much more than 'country', which just narrows things too much.''

Dean's award-nominated album Tyre Tracks & Broken Hearts has a strong Dunedin connection, having been largely recorded at the University of Otago's Albany St Studios last year.

The album was produced by Dunedin multi-instrumentalist and music lecturer John Egenes, whose direction was ''vital'' to the result, Dean says.

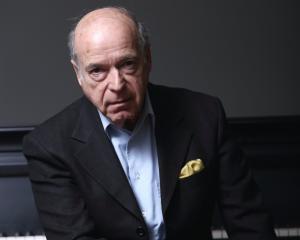

''John really got me and the songs and knew how to bring the right ingredients to the pie. I could hardly take the grin off my face when, to my amazement, John brought Gurf Morlix in on the deal,'' she says of the involvement of the 2009 Americana Music Association's Instrumentalist of the Year.

The inclusion of American guitar greats Albert Lee, Redd Volkaert and Amos Garrett notwithstanding, Tyre Tracks & Broken Hearts also benefited from a strong local rhythm section, Dean says, pointing to the work of bass player John Dodd and drummer Marcel Rodeka.

''These two are at the top of their game ... We were after something organic and I feel we got that. Nothing is on the tracks that didn't need to be.''

Though Dean says she has ''stacks of unfinished ideas'', she prefers to enter the studio with a bunch of songs written especially for an album.

''Some songs are about something personal to me and others are bits of fiction and fact rolled into one. I like to write about `people stuff'.

''I'm a people watcher. It's a bit like watching a fire in the dark - sometimes it's smouldering, smoking, crackling, raging and sometimes quiet and comforting. I observe what happens to my insides, my emotions when a situation opens out from a park bench or on the street somewhere and a song might creep through from there.

''Right now I'm reading Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America's Original Roots Music Hero Changed Pop Sounds Of A Century, by Barry Mazor.

''It's a fantastic read and opened my eyes to his influence not just to country, folk and blues music but rock and pop. He wrote some of the first songs I ever heard, long before I ever knew his name.''