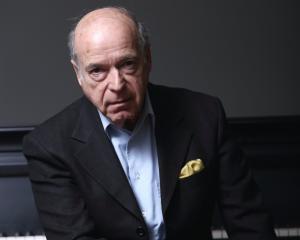

New Zealand's outdoor lifestyle and scenery is drawing Samuel Jacobs back to the country to play with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. The French horn musician tells Rebecca Fox about his Kiwi connections.

It might be a brief visit this time but come next year Samuel Jacobs will be coming back for good.

The Englishman has spent the past two and a-half years as the principal horn in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London but has missed his friends and the lifestyle in New Zealand.

He spent two years from 2012 as section head in the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra before being lured back home for the position at the RPO.

"It was my dream. Since college days its been my goal to be a principal in a London orchestra.''

It was a difficult decision at the time because he had a new Kiwi girlfriend (now his wife) but she decided to go with him to London.

"It was a tricky one but bringing her over and being closer to family it all seemed like a good solution.''

He enjoyed the work and the travelling the RPO offered.

"I've had a great time at the RPO.''

Still doing some freelancing when he was able to, he returned briefly to New Zealand to play with the NZSO which was temporarily in need of a French horn player.

"It was the first time I'd been back and it was a fantastic experience. Great to see old friends.''

Talk of him filling the vacancy continued when he returned to London and the RPO and he began to think it would be a good idea.

"It's been a full-on two and a-half years. Exhausting. I couldn't see myself doing this in 25 years.

In the meantime he was offered the chance to return again for Edo de Waart's Masterworks series.

"It was a chance to work with the new conductor and its a great programme with Strauss in the second half and they let me pick the concerto.''

He chose Mozart's Horn Concerto No 4 in E-flat Major because it best suited the occasion.

"Partly because it's the most well-known. It's a little bit more complex, more mature and well formed than one of the others. Four is the most sensible and most fun as well.

"People should come away with a smile on their face. It's playful, jaunty and light-hearted but at the same time has some serious musical ideas.''

When the offer of a permanent job at the NZSO was made, he was ready to take it.

"I missed the country, the lifestyle, scenery, the outdoors. It's the right time to come.''

It would mean his wife, Olivia, would be nearer her family and get to spend time with her new nephew, even though Mr Jacob would be further away from his family.

"We'll just clock up a lot of miles coming back, although it's a nice excuse for my family to come out on holiday.''

Ending up in New Zealand playing music was not what he envisaged when he first took up the French horn.

He was about 9 years old when his parents took him to a concert and he saw the trumpet played live for the first time.

"I thought it was cool.''

So he started lessons and after four years his teacher recommended he try the French horn.

"I didn't even know what a horn was. My dad quite liked the sound through.''

He tried out a horn in a music store, liked its sound and took it home.

"I was about 12 or 13 and I haven't stopped.''

The French horn was an "endangered species'' as it was hard to pick up at entry level, he said.

"It's not like a piano or violin where you can play a note straight away. You need to use a lot of muscles in your mouth that you don't normally use day to day.''

It also meant, no matter how practised you were, taking a break from the horn meant you lost any stamina in those muscles.

The main skill needed for the French horn, was having a good musical ear, as notes were notoriously difficult to pitch.

"You need to be able to hear the pitch you are aiming for before you play it so you can be as certain as you can positively be for the note to come out right.''

Patience, and understanding that it was not possible to get 100% of notes right every performance, were also important.

"If you only get five wrong notes that's a pretty good job. You have to have patience and acceptance to forget a mistake or else you get bogged down and the performance goes downhill very quickly.''

So people usually got put off but he found it was worth putting in the hours to get it right, as he enjoyed the lessons.

"I liked the sound of it. I had a good teacher which is a huge factor.''

Despite his enthusiasm for the instrument, it was not until he was studying music at university that he began to think it might become a career.

"I was 20 before I realised it was something I could do full-time. I was performing more and more and working with orchestras in northern England.''

He began as a freelance musician and found himself to be very busy with work.

Then one day the NZSO called, acting on a recommendation from one of his teachers, offering him a five-week stint in New Zealand.

"It coincided with the Rugby World Cup in New Zealand so I thought that's a great time to go. So I did the Brahms Symphony and then on days off went to rugby games.''

At the end of the stint he was asked if he wanted the job full-time.

"I'd had such a great time I said yes and came back three months later.''

He was single at the time and while close to family, knew it was not forever.

"I thought I might regret it if I turned it down.''

To see

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Edo de Waart's Masterworks, Haydn and Mozart, Dunedin Town Hall, tonight.