Contaminants that can be swept along for the ride range from dog faeces from footpaths to oil and petrol-fumes from roads and zinc released by metal roofs, says acting water and waste services manager Laura McElhone.

Other problems include people pouring leftover paint into drains and garden pesticides being washed by the rain off footpaths and into gutters.

"Once it's in the stormwater pipe, it's going to the ocean and people sometimes forget that."

In a few areas, groundwater from contaminated land may also be seeping into stormwater pipes.

Stormwater is rain that is collected from the roof or that flows over paved areas such as driveways, roads and footpaths. It is different from wastewater, which comes from domestic kitchens, bathrooms and laundries as well as from commercial and industrial sources. Both are discharged into the sea, but only wastewater goes to a treatment plant first.

The city's stormwater network includes 363km of pipe, ranging in diameter from 100mm to 1800mm, and about 8000 mudtanks. These grates in the kerb and channel are designed to separate out litter and sediment but they don't catch all of it and they don't stop chemicals.

Key concerns in Dunedin are the heavy metals: copper, zinc and lead, along with bacterial contamination and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (typically derived from engine oil, vehicle exhaust emissions, erosion of road surfaces and pesticides).

In the central city, some of the pipes are century-old,1.4m-high brick tunnels that Dr McElhone says are in remarkably good condition and probably have about 40 years left in them. There are also 11 stormwater pumping stations but gravity and watercourses are used where possible to save money.

Ultimately, the stormwater ends up in the harbour or off the coast via a series of outfalls, many of which have grilles to prevent large pieces of litter going into the harbour.

Water quality has been in the spotlight recently, with the Otago Regional Council changing its regulations to prevent runoff in rural areas polluting waterways. Now the council is turning its attention to stormwater discharges in urban areas, where new contaminant standards will eventually be set.

Territorial authorities believe the policies implemented in country areas and labelled too restrictive by many farmers could flow on to urban areas.

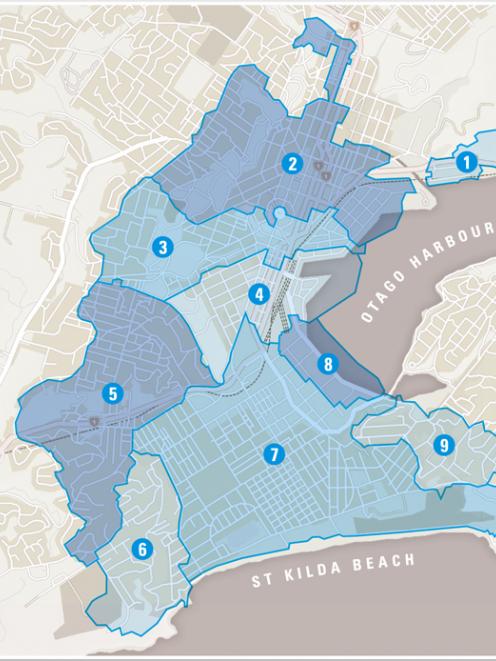

The changes come as the Dunedin City Council applies to the regional council for consent to discharge stormwater into Andersons Bay Inlet, St Clair, Port Chalmers and the OtagoHarbour basin.

Stormwater from residential catchments does not requireapproval but these discharges are classified as a controlled activity because they are from areas that have trade and industrial premises.

The existing consents expire at the end of this month but will stay in force until the two councils resolve any areas of contention - a process which could be a lengthy one given their oposing views.

Two issues are the level of treatment necessary and the use of mixing zones - areas in the coastal waters where quality standards can at present be exceeded to achieve reasonable mixing of discharges.

The regional council says there should be regulations to minimise contaminants from key sources such as industrial sites and subdivisions and when old pipes need to be replaced, the city council should take the opportunity to install internationally accepted treatment devices, such as vortex separators. If those things were done, mixing zones should not be necessary in most cases.

The city council says costs and technical constraints make this kind of catchment-wide treatment inappropriate and spending large sums of money on end-of-pipe treatment may not lead to measurable improvements in the harbour. It feels it is better to control what goes into the stormwater at the source, with targeted treatment where needed. A dedicated stormwater bylaw would underpin this approach and more industries might be required to have on-site treatment.

Dr McElhone says the council does need to reduce the contaminant load because that is what the public has said it wants. But the harbour is already a modified environment, with sediments contaminated from early industries, and would not suddenly flourish even if there were no stormwater in it.

"If you look at the pure science, our belief is that the impact that stormwater is having on the harbour is not that significant."Otago Regional Council resource management director Dr Selva Selvarajah says that might be the case if one took the whole harbour as an entity but not if one looks at the receiving area.

"We've got to be mindful of the good practice that we can adopt. Just because an environment provides a bit of mixing, doesn't mean we'll continue to allow a large number of contaminants into [it]."The applications have attracted seven submissions and will be heard once a panel of independent commissioners is appointed.

Stormwater do's and donts

THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS SHOULD NOT BE DUMPED INTO STORMWATER DRAINS OR THE GUTTER because they will flow into streams, lakes or the sea and can be toxic to wildlife:

• Automotive products, including motor oil, antifreeze, brake fluid, diesel, transmission fluid, degreasers, petrol and radiator water.

• Paints and solvents, including all types of paints, paint thinners and strippers, rustproof coatings and turpentine.

• Recreational products such as swimming-pool chlorine and water, bilge water and spa-pool water.

• Pesticides, including insecticides, fungicides, rodent baits, herbicides, molluscicides and wood preservatives.

• Cleaning products, including caustic degreasers, disinfectants, detergents, drain and toilet cleaners, leather preservatives, dry-cleaning agents, polishing agents and household cleaners.

• Some hazardous materials can be recycled, while others should be disposed of at a transfer station or landfill. Contact your local council for more information.

WHAT YOU CAN DO:

• Wash your car on the lawn to stop detergent and oils getting into drains.

• Wash your paintbrush at an inside sink or on the lawn or garden.

• Pick up animal droppings.

• Put litter, including cigarette butts, in rubbish bins.

• Dispose of excess paint and chemicals in the hazardous waste area at landfills.

• Service your car regularly so oil does not leak into the stormwater system.

• Anyone doing building work involving earthworks must prevent sediment leaving the site and may need a documented sediment control plan.

• Industrial and commercial premises must comply with the stormwater requirement in the trade waste bylaw and ensure chemicals cannot get into the stormwater. In some cases they may have to provide on-site treatment.

• If you see pollution in or near a waterway, contact the Otago Regional Council's 24-hour pollution hotline, 0800 800 033. Dunedin residents who want more specific advice, or want to report an accidental spill or the illegal tipping of hazardous materials into a gully trap or manhole, should call the Dunedin City Council on (03) 477 4000.

CONTAMINANTS PRESENT IN DUNEDIN'S STORMWATER

• Total Suspended Solids (TSS): Erosion, including stream-bank erosion. Can be intensified by vegetation stripping and construction activities.

• Arsenic (As): Combustion of fossil fuels; industrial activities, including primary production of iron, steel, copper, nickel, and zinc.

• Cadmium (Cd): Zinc products (Cd occurs as a contaminant), aluminium soldering, ink, batteries, paints, oil spills, industrial activities.

• Chromium (Cr): Pigments for paints and dyes; vehicle brake-lining wear; corrosion of welded metal plating; wear of moving parts in engines; pesticides; fertilisers; industrial activities.

• Copper (Cu): Vehicle brake linings; plumbing (including gutters and downpipes); pesticides and fungicides; industrial activities.

• Nickel (Ni): Corrosion of welded metal plating; wear of moving parts in engines; electroplating and alloy manufacture.

• Lead (Pb): Residues from historic paint and petrol (exhaust emissions), pipes, guttering and roof flashing; industrial activities.

• Zinc (Zn): Vehicle tyre wear and exhausts, galvanised building materials (e.g. roofs), paints, industrial activities.

• Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Vehicle and engine oil; exhaust emissions; erosion of road surfaces; pesticides.

• Faecal coliforms/E.coli: Animal faeces (birds, rodents, domestic pets, livestock), wastewater.

• Fluorescent Whitening Agents: Constituent of domestic cleaning products.