Scientists warn New Zealand is not pulling its weight on climate change and is unprepared to meet the needs of the most vulnerable. The Government, however, says the country is doing its share as it readies itself for unavoidable impacts and potential opportunities. Bruce Munro looks at reactions to this week's release of the latest global report on climate change.

The treadmarks of a wide tyre, common on the large, low-slung vehicles favoured in this suburb, have left a deep impression on the still-soft grass verge at the corner of Hargest Cres and Alma St, South Dunedin.

Adjacent, on a broad, rough asphalt driveway, a group of young men in caps and singlets shoot hoops against a garage that has seen better days.

Leaning on the fence, watching his brother and their friends at play, is Ruia Morgan.

It is mid-afternoon in the middle of the week.

Rain has not fallen for seven days, but the ground is still soft. It is always like that, Mr Morgan says.

''Every time there's decent rain, the grass here and in the backyard fills up like a puddle,'' he says. ''It takes a few days to go away.''

The 27-year-old polytechnic trades trainee, who lives at home with his mother and three brothers, is well aware the regular flooding is exacerbated by the high underground water table in South Dunedin. He has no knowledge, however, of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released this week which says sea-level rise will only make the problem much worse.

In all of Otago, it is here the most noticeable impacts of climate change might well be seen. In four instalments spread over a year, the IPCC is releasing its fifth global assessment, a multi-volume boil-down of robust scientific climate-change studies from throughout the world.

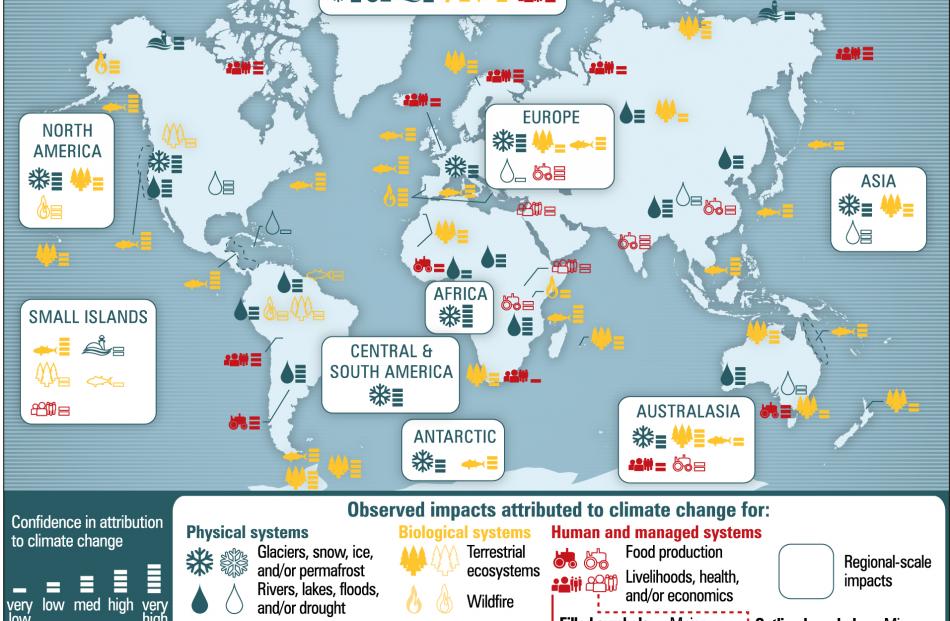

This week in Yokohama, it released the second report which covers the effects that have already been seen, the expected impacts of greenhouse gas emissions, and steps that can be taken to manage and adapt to the likely impacts.

Globally, during this century, water resources will be depleted and crop yields will decrease in many regions, the report says. Extreme weather events such as heatwaves and heavy rain and snow will increase.

Sea-level rise will cause increased flooding and erosion. Ocean acidification could threaten polar and coral reef ecosystems.

Temperature and humidity increases might make it impossible to work outdoors in some regions for parts of the year. The report includes a 101-page chapter on Australasia.

Joint lead author of the chapter is Dr Andy Reisinger, of the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre.

Dr Reisinger warns if steps are not taken to mitigate and adapt to climate change there could be ''substantial impacts'' to New Zealand and Australia's water resources, coastal ecosystems, oceans, infrastructure, health and agriculture.

Key risks for New Zealand include increased flooding and wildfires, and coastal damage from sea-level rise. By 2100, what have been 1-in-100-year climate events could happen annually, perhaps more frequently. The upsides could be less energy demand for winter heating and more spring pasture growth in cooler regions.

Scientists have reacted strongly to the report.

Associate Prof James Renwick, of Victoria University, says the report's statement that there has been a ''significant adaptation deficit'' should be interpreted ''we have done little so far to prepare''.

''It is critical to develop serious mitigation measures to ... avoid the worst of what the future has to hold,'' Prof Renwick says.

Judy Lawrence, of the New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute, says it shows ''New Zealand is under-prepared for climate changes''.

''Institutionally our devolved planning system leaves each local government to fend for themselves,'' the climate researcher says.

''Scientifically, there is only a patchy picture of where the highest risks lie and who are the most vulnerable.''

Her comment about vulnerability picks up on an issue highlighted in the chapter's executive summary.

It says there is only limited understanding of who will be most vulnerable because little attention has been given to how socio-economic factors interact with climate change.

Further on in the chapter, it says poverty and income inequality is high in Australia and New Zealand by developed nation standards and has increased significantly in the past 30 years. This is important because demographic, economic and socio-cultural factors influence the vulnerability of individuals and communities and their capacity to adapt.

Social and psychological climate-change impacts are not being adequately monitored. They remain hidden in the shadow of environmental and economic impacts, the chapter says.

In Otago, the issue shines a glaring spotlight on South Dunedin.

Large swathes of ''South D'', as many locals call it, have a deprivation rating of 9 or 10 according to the New Zealand socio-economic deprivation index. Low income, low educational outcomes, high unemployment, poor diet and inadequate housing all conspire to make it the most deprived area in Otago and the third-most deprived in the South Island.

Mr Morgan was born and raised in South Dunedin. He knows paying rent is a struggle, but that trying to find affordable accommodation elsewhere is even more difficult. He has no idea long-term solutions for his patch may include a network of pumps and drains to protect the former swamp from continual flooding, or even a managed retreat from the whole area.

Low-lying South Dunedin faces some severe climate-change challenges. A 2010 report said sea-level rise could force a partial or complete evacuation of South Dunedin, St Kilda and St Clair by the end of the century.

In the meantime a moratorium on new residential development is on the cards for the area.

A report detailing possible long-term responses is set to be considered by the Dunedin City Council in June.

This week, Gavin Palmer, the Otago Regional Council engineering, hazards and science director, said the council had been including climate-change considerations in its work for many years.

He also said the regional council was working with its city counterpart and other Otago councils to ensure climate-change information was considered.

This is good as far as it goes. But New Zealand needs a nationwide approach, scientists say.

''A key challenge for the Government,'' Dr Reisinger says, ''is to identify when and where adaptation may have to go beyond incremental measures and more transformational changes may be needed, and how to support such decisions.''

Others, such as Prof Tim Naish, the Antarctic Research Centre director, put it more bluntly.

''This report is a wake-up call for New Zealand to take its head out of the sand, to take a longer-term view - at least longer than an electoral cycle.''

Prof Euan Mason, of the University of Canterbury, says New Zealand is simply ''not pulling its weight''.

He says our Emissions Trading Scheme could enable us to be fully greenhouse gas neutral.

''That we choose instead to do less than our share to solve the problem is shameful,'' Prof Mason says.

But Tim Groser, Minister of Trade and Minister of Climate Change Issues, is of a different opinion. He can even see a silver lining.

He says each local government is best placed to plan for climate change in their specific area, with guidance and information from central government.

''New Zealand is committed to doing its fair share to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions,'' Mr Groser says.

''We will meet our commitment to reduce emissions to 5% below 1990 levels by 2020, and we are investing heavily in international agricultural research on ways to grow more food without growing greenhouse gas emissions.''

He welcomes the new IPCC report's focus on adaptation.

''The report backs the view that adaptation is an important part of dealing with climate change that cannot be ignored,'' he says.

''While much of our focus is on getting international agreement on reducing emissions, some change can't be avoided so we must be prepared to adapt.''

The whole topic, and possible implications, leave Mr Morgan feeling uneasy and nursing unanswered questions.

''South Dunedin is our home. It's not easy to leave your home,'' he says.

''If they were to move people, where would they go? Who would help them?''

Climate change in New Zealand

- Rising snow lines, more frequent hot extremes, less frequent cold extremes and increasing extreme rainfall.

- Regional sea level likely to rise by 1m this century.

- Annual average rainfall expected to decrease in the northeast South Island and northern and eastern North Island, to increase in other parts of New Zealand.

- Rainfall changes projected to lead to increased runoff in the west and south of the South Island and reduced runoff in the northeast of the South Island, and the east and north of the North Island.

- Annual flows of eastward-flowing rivers with headwaters in the Southern Alps projected to increase in response to higher alpine rainfall.

- Flood risk projected to increase in many regions due to more intense extreme rainfall caused by a warmer, wetter atmosphere.50-year and 100-year flood peaks for rivers in many parts of the country will increase, with a corresponding decrease in return periods for specific flood levels.

- Flood risk near river mouths will be exacerbated by storm surge.

- Very high and extreme fire weather in many, in particular eastern and northern, parts of New Zealand will increase.

- Fire season length will be extended in many already high-risk areas, reducing opportunities for controlled burning.

Key global climate change risks

- Risk of death, injury, ill-health, or disrupted livelihoods in low-lying coastal zones and small island developing states and other small islands, due to storm surges, coastal flooding, and sea-level rise.

- Risk of severe ill-health and disrupted livelihoods for large urban populations due to inland flooding in some regions.

- Systemic risks due to extreme weather events leading to breakdown of infrastructure networks and critical services such as electricity, water supply, and health and emergency services.

- Risk of mortality and morbidity during periods of extreme heat, particularly for vulnerable urban populations and those working outdoors in urban or rural areas.

- Risk of food insecurity and the breakdown of food systems linked to warming, drought, flooding, and precipitation variability and extremes, particularly for poorer populations in urban and rural settings.

- Risk of loss of rural livelihoods and income due to insufficient access to drinking and irrigation water and reduced agricultural productivity, particularly for farmers and pastoralists with minimal capital in semi-arid regions.

- Risk of loss of marine and coastal ecosystems, biodiversity, and the ecosystem goods, functions, and services they provide for coastal livelihoods, especially for fishing communities in the tropics and the Arctic.

- Risk of loss of terrestrial and inland water ecosystems, biodiversity, and the ecosystem goods, functions, and services they provide for livelihoods.* Key risks are potentially severe impacts that the IPCC report ''Climate Change 2014 Impacts, Adaptations and Vulnerability'' identifies as ''high confidence''.