Myths and mysteries surround William Larnach and his family, their extravagant castle on Otago Peninsula and their Gothic memorial tomb in Dunedin's Northern Cemetery. As a new effort is launched to conserve it, Charmian Smith tries to dispel some of the myths surrounding the now derelict mausoleum.

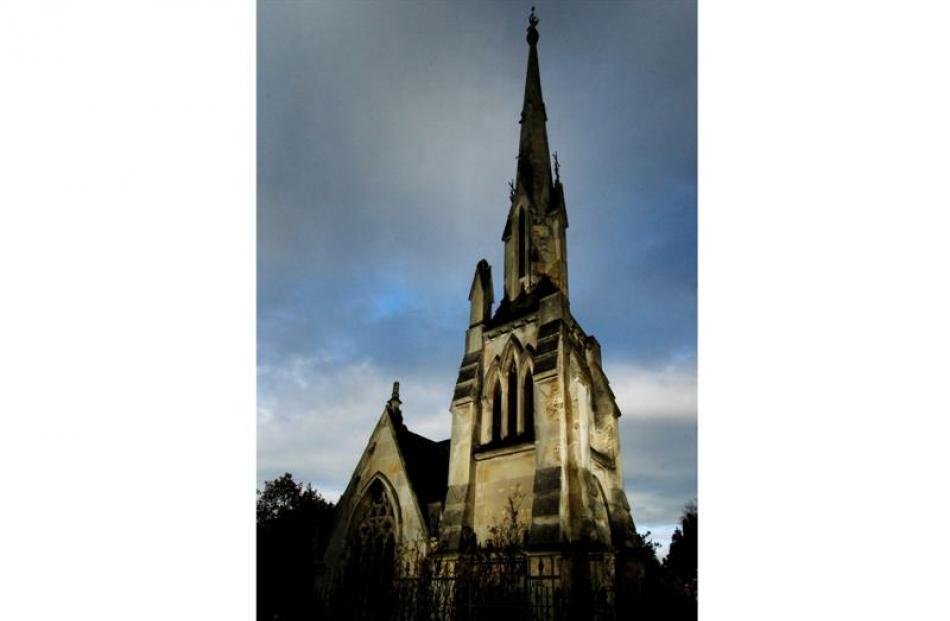

For almost 130 years, the most striking memorial in Dunedin's Northern Cemetery has been Larnach's tomb.

To the left as you enter the gate, the soaring 17m spire of the memorial chapel is visible well above the surrounding monuments of other wealthy Dunedin families - in an area known as millionaires' row.

The plots are large, fand William Larnach bought three and a-half of them to erect the ostentatious funerary monument, a conspicuous display of wealth and status common in late-Victorian times.

The mausoleum was designed by the notable architect R. A. Lawson in 1881 in the form of a Gothic chapel, modelled on his graceful First Church, built in 1873.

William James Mudie Larnach, banker, businessman, politician, government minister, and builder of the grandiose house, The Camp, now known as Larnach Castle, on Otago Peninsula in the early 1870s, was no stranger to flaunting his prosperity, however precarious it ultimately proved to be.

He built the mausoleum in 1881 as a memorial to his first wife, Eliza Jane Guise, who died suddenly on November 8, 1880, of an apoplectic fit, now called a stroke. Her name and dates of birth and death can still be made out carved on the door lintel, now sadly defaced.

Subsequently also buried there were Larnach's second wife Mary Cockburn Alleyne, Eliza's half-sister, who died of blood poisoning after an operation in 1887; his eldest daughter Kate Emily Larnach, who died of typhoid in Wellington in 1891; and Larnach himself, who committed suicide in Parliament buildings in 1898.

It is said to have been due to the parlous state of his finances, but is also speculated to be because of an affair between his third, much younger wife, Constance de Bathe Brandon, and his younger son Douglas. In 1910, Larnach's elder son, Donald Guise Larnach, who also committed suicide, was buried there too.

Larnach died intestate and his family was torn apart by legal battles over what little remained of his property. The castle was sold in 1906, went through several different ownerships and fell into various states of disrepair.

Now carefully restored by Margaret and the late Barry Barker, who bought it in 1967, it is a major showpiece and tourist attraction.

The dramatic story of Larnach's colourful life and dysfunctional family has been told in a play, Castle of Lies, by Michaelanne Forster (Fortune Theatre 1993), an opera, Larnach, by John Drummond (Opera Otago 2007), in biographies The Ordeal of William Larnach (1981) by Hardwicke Knight, and King of the Castle (1997) by Larnach's great-great-granddaughter, Fleur Snedden.

Larnach's tomb has found no such saviour. It is derelict. It is a wonder it has survived at all. Not only have the wind and weather wreaked havoc on the Oamaru stone and slate, the tomb has also been continually vandalised and desecrated - the stained-glass windows and stone mullions shattered, the doors broken, many stones smashed and pulled apart.

Graffiti defaces the walls inside and out - not that it is the only vandalised memorial in the cemetery.

From at least the 1950s there have been reports and complaints of vandalism and drunken parties held in cemeteries. Memorials have been defaced, broken or knocked over. Stewart Harvey, chairman of the Historic Cemeteries Conservation Trust says older cemeteries in cities suffer more vandalism than country cemeteries.

An editorial in the ODT on January 18, 1972, in the midst of a furore about one of the desecrations of the Larnach memorial, said the pretentiousness of the tomb seemed to draw vandals and iconoclasts, and spoke of a drunken Black Mass held there less than 20 years earlier.

It was probably not the first and certainly not the last of the alcohol-fuelled parties held in the tomb, going by the evidence left over the years.

Like William Larnach and his castle, the tomb attracts stories and legends like a lightning rod, according to Peter Entwisle. The Dunedin historian and art curator should know, as he is implicated in one of the myths.

"I didn't steal Larnach's bloody skull but people believe that I did, so that's the bottom line. And I certainly had a skull, that's for sure, and that's not a crime," he said in a recent interview.

In January 1972, when he was a 23-year-old student, he was charged in the Dunedin Magistrates Court with improperly interfering with human remains, those of William Larnach. According to reports in both the Otago Daily Times and the Evening Star, he was not represented by a lawyer, pleaded guilty, was convicted and remanded for a probation report and sentencing.

The police, acting on information received, had found a skull in his flat. Entwisle said it was readily identifiable as Larnach's by the gunshot wounds and it had been given to him about a year earlier by a friend, whom he declined to name. As a graduate anthropology student he had an academic interest in skulls, he said then.

However, what is not widely known is that the case was dismissed on January 31. Entwisle was then represented by Ron Gilbert and changed his plea to not guilty. According to reports in the Otago Daily Times, magistrate Mr J. D. Murray said a corpse or human remains was not something that could be stolen so Entwisle could not be charged with receiving.

Although he had kept the remains, occasionally polishing them and showing them to friends, he had not mutilated them, so there was no improper interference.

Another persistent myth is that the coffins were originally suspended from the roof by chains, something maintained by one Bill Bachop who heard it from his friend Barry Barker, also claimed by Peter Entwisle and repeated from time to time in newspaper reports.

Since the roof was repaired after an arson attack in 1999 there is now no evidence of anything that might have supported the coffins, some of which were lead-lined. A photo of Mr Bachop and Mr Barker in the mausoleum in 1972 or 1973 clearly shows the ceiling.

Although there are strands of ivy coming in the broken windows, the roof arches and beams appear to have no hooks or other paraphernalia for suspending coffins.

Gill Hamel, an archaeologist who inspected the tomb for the Historic Places Trust in 1987, confirms this as she did not notice anything which might have been used to suspend the coffins.

Prof James Stevens Curl, British architectural historian and author of The Victorian Celebration of Death, said in reply to an email query:

"I have never heard of lead-lined coffins being suspended from ceilings, and I really think this must be nonsense. In the first place, such coffins are extremely heavy, and there is a danger that if they were suspended, the weight would either break the chains or pull the hooks out of the ceiling, or the weight would distort the coffin, which would then bend and disgorge its unpleasant contents.

"If ropes were used, disaster would happen quite soon. The problem with heavy coffins in vaults is that they must have support, and that is usually in loculi [burial niches] or on shelves of stone.

"However, lead coffins were usually encased in wood, and if water gets at the wood it will rot, and if it rots and the coffin collapses the lead often bends and fractures too, again causing problems, as bodies behave in different ways when enclosed in airtight boxes: some liquefy, some dry, some merely decompose very slowly.

"In all cases the process is not pleasant, which is why rapid dissolution in well-drained soil is preferable and more 'eco-friendly', to use a ghastly modern expression.

"Coffins in vaults, therefore, had to be raised slightly to allow air to circulate under: if this did not happen condensation, etc, could cause rot underneath, with predictable results, so I expect the notion of `suspension' suggests that the coffins were slightly raised to support them on a series of blocks.

"If no shelves or loculi were built, then the coffins would have been placed either side by side or on top of each other: inevitably they decay, collapse, and shed their contents. I have seen many such hideous instances of this," Prof Curl wrote.

There is another story that the coffins were lying on the floor of the chapel and visible through the windows, but it is more likely they were in the concrete vault which was built before the superstructure.

Lawson's specifications for building the memorial chapel, dated May 16, 1881, six months after Eliza's death, clearly talk about removing "soil from the cover of the vault at present in the ground" and that its walls were to be raised where necessary.

His drawings show the vault and the details of how the removable wooden floor that would cover the entrance was to be constructed, and tiles, similar to those at the castle, laid around the edges and in the entry porch under the spire.

This is confirmed by heritage consultant Guy Williams, who recently investigated the building for a proposed restoration. The vault was obviously built before the chapel, but whoever built it must have had some idea of the structure that was going to go above. Part of the vault extends under the wall of the chapel and has an arched roof, he said.

The vault is unlikely to have been ready for Eliza Larnach's funeral on November 16, 1880, eight days after her sudden death, even though the event was postponed until William Larnach arrived back from Melbourne.

A notice in the ODT said her funeral would leave for the Northern Cemetery at 2pm from Manor Pl, the Larnachs' rented townhouse, but there seem to be no subsequent reports on it.

Victorian funerals tended to be grandiose occasions, including processions of carriages, the hearse and many followers, and, knowing Larnach's love of display, this would probably have been no exception.

The coffin would have to have been stored somewhere cool, perhaps at the undertakers' premises, until the vault was ready to take it. The Larnachs' undertaking firm, H. Gourley, was incorporated into the present day firm of Gillions but they do not appear to have records of this time.

However, Derek Hope, whose family members have been funeral directors in Dunedin for four generations, confirms this would have been the case here as well. Prof Curl says it was illegal to remove a coffin from the cemetery after the funeral in Britain, although it is not certain whether this was the case in New Zealand as well.

In British cemeteries coffins could be stored in a temporary vault or a mausoleum, possibly at the undertakers' premises or in a temporary tomb or catacomb until the family vault was ready, he said. The record of Larnach's purchase of three adjacent burial plots was dated December 8, 1880, although the actual purchase may have been earlier.

Despite the 1972 brouhaha about the state of the tomb, which had been triggered by a letter to the editor of the ODT in the news doldrums of early January, it had obviously been damaged "some considerable time" earlier, according to newspaper reports.

In fact, the dilapidated state of the tomb had been mentioned in Parliament as early as the 1920s. This sparked a flurry of letters in 1927 between the Public Works Department on behalf of the War Graves Division of the Department of Internal Affairs and the Dunedin town clerk, about the work that needed to be done, including painting, cleaning, repairing broken stained glass and slates, and renewing fallen finials and rusted downpipes.

It appears not to have been desecrated at this stage. However, the city, which owned the cemetery, disclaimed responsibility for the upkeep of private memorials, there was no legal authority for spending public money on private monuments, the Larnach estate had no funds to repair it, there were no descendants in Dunedin, and the only remaining son, Douglas Larnach, was not in affluent circumstances, so nothing seems to have been done.

A report in the Evening Star (December 4, 1953) reports damage to the tomb - broken windows, the lid wrenched off one of the coffins and the railing outside badly damaged, although it had not been done recently.

According to Margaret Barker, Larnach's granddaughter, Colleen Pedersen, paid for some maintenance on several occasions, but could not afford to keep up with the continual damage caused by vandals.

She more than once paid for leadlight replacements of the original stained glass, which had been "of the same quality and style as the glass work in the castle", Ms Pedersen said from Auckland before she died, according to stained glass artist Peter MacKenzie, who has researched the tomb's stained glass for possible restoration.

Lack of funds for upkeep and repair is a continuing problem. Some work appears to have been done about 1950 or perhaps in the 1960s, although details are hard to come by.

Jack McLeod, who had taken over the job of sexton at the Southern Cemetery from his father and took over the Northern Cemetery as well in the mid-1960s, said a woman walking her dog in the cemetery one morning was shocked to find a skull and crossbones on one of the grass paths.

The bones had come from Larnach's tomb and Mr McLeod, in the company of a policeman, was required to replace them. The desecrator had climbed in a broken window and broken the cover over the vault to get to the coffins, he said.

He replaced the skull and bones in an opened coffin. It must have been one of the women's coffins, because its occupant's hair was still there. After that the vault was sealed by the council, he said.

A buildings classification report in the city council's cemetery archives dated 1989, based on a Historic Places Trust report of about the same time, says "four or five coffins" lying in the chapel were put into the crypt and the floor was concreted in about 1950 by H. S. Bingham and Co, monumental masons.

The source was a Mr Jopson who worked for Bingham's at the time. Ian Bingham, whose father Claude owned the firm then, confirms he remembers him talking about concreting Larnach's tomb.

However, after the furore of 1972, Barry Barker and Bill Bachop formed the Friends of Larnach's tomb, and received permission from descendants to tidy the tomb and concrete the floor to seal the vault, which they did in May 1973. Mr Bachop says there were no signs of any previous concreting.

This appears to be backed up by a photograph from the ODT files, taken at the time of the 1972 kerfuffle, showing wooden floorboards ripped up, exposing the steps and coffins in the vault below.

There is no sign of the remains a concrete or plastered floor covering the vault in the photograph, and the diagonal tongue and groove floorboards are as they were shown in Lawson's drawing, according to heritage consultant Guy Williams.

Mystery seems to have reared its head again, as Mr Bachop and Mr Barker were surprised to find five coffins when they only expected four. It took a day or two for them to find out Donald Larnach had been buried there as well as Larnach, his first two wives and his daughter.

Reporters at the Evening Star in 1967 (August 12, pg 10) were also unaware of these details when they said nobody seemed to know who was buried there and speculated it was Larnach and his three wives.

The coffins were found, in 1972, to be in two stacks, one of three and the other of two, lying north-south. Three were undisturbed, one had its lid removed with the lead lining still intact, and the other, Larnach's, had been opened and bones scattered about, according to Mr Bachop.

They returned the bones, some that had been scattered outside the tomb, to Larnach's coffin, leaving the skull and reports of the incident in a box on top of the coffin. Mr Williams, who had a hole drilled in the floor and investigated the crypt using a camera, confirmed this.

◊ The ODT is interested to hear from anyone who has early photographs of the tomb, or any other information about the building. charmian.smith@odt.co.nz Historic Cemeteries Conservation Trust of New Zealand, www.cemeteries.org.nz Stewart Harvey, stewarth@orcon.co.nz, ph (03) 454-5384.