But even in Orania, where a small community of Afrikaners has closed itself off, intent on preserving its culture and language at all cost, the global icon who preached a contrasting ideology of racial integration commands respect.

Hours after President Jacob Zuma announced the 95-year-old's death, South Africans of all races took to the streets and the Internet to express sorrow at his passing and celebrate his remarkable life.

Former President F.W. De Klerk, the last white president who help dismantle the apartheid system of institutionalised racism, said Afrikaners had "very warm feelings towards Nelson Mandela" and would mourn him.

In Orania, however, the roughly 1000 residents were unmoved.

"One can genuinely sympathise with the death of a person who is a father to someone, a husband, a friend to others without falling in love with that person," said Carel Boshoff, president of the Orania Movement and son of its founder.

"But this was a great person. We can recognise it, we can see it and as such we can reach out and say we shared something of a commonality around this person. He had more grace, more presence than many others."

A group of young people sitting at a cafe sipping drinks, eyes glued to a television screen tuned to an Afrikaans language channel, merely shrugged silently when asked whether they had been monitoring media coverage of the story.

"DON'T KNOW MUCH ABOUT HIM"

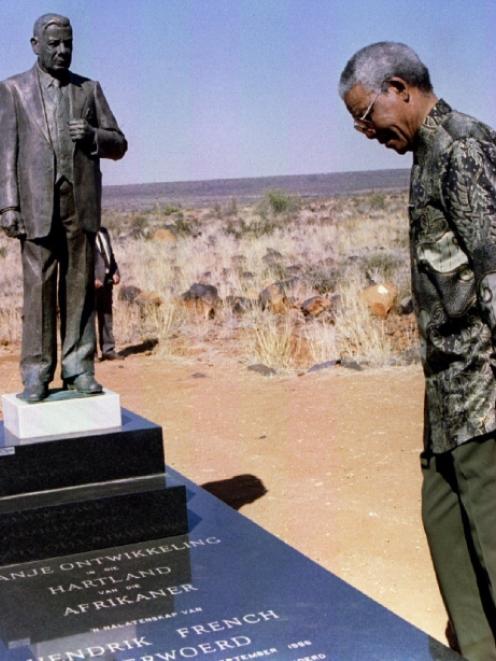

Mandela, who became South Africa's first black president in 1994 after spending 27 years in jail for fighting white rule, astounded Orania's residents when he visited the settlement the following year as a gesture of conciliation.

The image, published in papers across the world, of the towering Mandela with his arm around the widow of apartheid architect Hendrik Verwoerd after the two shared tea, cemented his stature as one of the world's most respected statesmen.

"I identify myself with the wishes of my people for a volkstaat (people's state) which I believe could be developed in this part of the country," Betsie Verwoerd told Mandela in Afrikaans during the visit.

"I want a united South Africa where we can cease to think in terms of colour," Mandela responded.

The visit triggered mixed emotions, including anger from some black and white South Africans.

But 18 years later, the memory appears to have faded from this self-contained community, which shuns contact with the outside world to the point of having its own currency, the Ora.

"I don't really know much about him," one elderly woman said when asked about Mandela's death, before quickly walking away, reflecting the suspicion that greets any visitor, especially a non-white reporter.

South Africa's high crime rate, particularly the killing of hundreds of farmers in Afrikaner communities, some by their black workers, played a major role in Orania's creation in 1991.

Residents deny charges of racism, but remain uneasy about life in a South Africa led by a black-majority government after decades of white minority rule. In essence, they just want to be left alone.

"We don't want to ask anybody's permission. If you constitute yourself and act in an orderly way within the broad lines of a constitution you shouldn't need anybody's permission to be - you should just be," said Boshoff.

"These are ideals Mandela himself respected."