Constructing policy around continued economic growth is a fool's errand, suggests Murray Grimwood.

Has Mr Obama missed his chance?

Sooner or later, someone has to do the "fireside chat" thing.

Has to take the anything-but-confident populace into their confidence.

Tell it like it is.

Do not hold your breath.

For a start, politicians are only allowed to spout optimism, or face oblivion.

Even when the gloomsters are correct - like Winston Churchill during the 1930s - they are not taken seriously until the paradigm they predict has undeniably arrived.

Mr Obama's problem is the International Monetary Fund's problem, Angela Merkel's problem; indeed, everyone's.

In a nutshell, Thomas Malthus was right.

Donella Meadows was right.

King Hubbert was right, and droll old Prof Albert Bartlett, is perhaps the rightest of the lot.

The greatest shortcoming of the human race, he says, is our inability to understand the exponential function.

Hear hear.

For some reason (which presumably has its origins in a past phase of our evolution, and therefore our survival) we seem to think in linear terms.

Growth is good, we are told and believe: 3% growth is ho-hum, 10% is desirable, and a recent reported quoting of year-on-year growth rates of over 100%, went unchallenged.

Three percent growth doubles in 24 years; 10% doubles in 7 years, and 100%, of course, every year.

Imagine a truckload of sand dumped in your driveway.

The first night after tea, you shovel away one shovelful.

The next night, two shovelfuls.

The next night 4, then 8, 16, 32, 64 ... doubling, in other words.

I do not have to know the size of that pile, to know what happens in the final three nights.

Three nights, from gone, to finished.

Nobody sees it coming: Beware the exponential function, says Bartlett.

That last night I will bet you spent much time scraping up the dregs, and that they were contaminated with gravel from the drive underneath.

The quality, in other words, was way down compared with that clean pile you started into.

Similarly, it took more energy on your part to obtain each shovelful towards the end.

Now add inevitably increasing cost; a similar, and compounding problem.

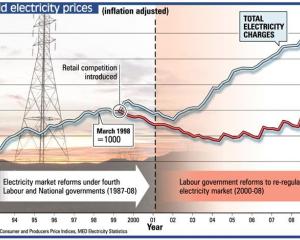

I was at a lecture by David Caygill (Chairman of the Electricity Commission) recently.

He was asked a simple enough question: Why do our power prices always go up?

Well, he said, each time a new generating plant is needed, it tends to be the cheapest option that is selected, and this of course has to be paid for.

The next plant will be the next cheapest, which means "more expensive".

So at every step, the price per unit has to increase.

The linchpin of them all, of course, is energy.

Not one activity, or more precisely not one economic activity, happens without energy.

At present, that is fossil fuel energy, and there are graphs overlaying energy-use with GDP, clearly showing this correlation.

Peak Oil is essentially the point on the graph where we are halfway through the pile.

There are some interesting points to note at that juncture: Even doubling the known resource would only push "Peak" out to 2030.

Peak is not "peak quality".

We tend, as Mr Caygill noted, to use the cheapest first, to which I would add "best quality".

In other words, we have cherry-picked the resource.

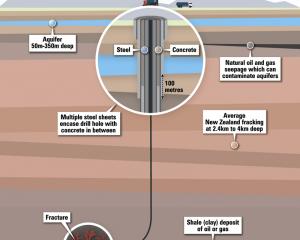

Now, it's deep ocean, sour crude, water-cuts, shale, tar-sands, all sub-optimal.

All energy-producing countries are increasing their internal use, meaning less left over for importing countries.

If we have to fuel economic activity with a reducing supply (and quality) of energy, then no claims of future growth can be made, without first ascertaining whence any savings can be culled.

Efficiencies are one such, and an essential, so much so that we can confidently pursue them on an all-out basis.

The paradox, of course, is that no matter how hard/fast we apply ourselves, the goal posts will always be receding, and at increasing speed.

Essential but inadequate, then, are efficiencies.

Which leaves a minor debate about discretionary use versus essential use, and their comparative effects on GDP, assuming GDP is the appropriate yardstick.

Basically, growth potential (global average) stopped with the peak of energy supply, give or take efficiencies.

It is a little more complex than that, in that we do not account properly for "natural capital", but essentially, those who suggest growth can continue, have to be wrong.

Those who advocate growing populations (or whatever) as being good, have to be wrong too.

More resource per-head simply has to be better.

Nobody, Mr Obama included, can prophesy exactly where it will go, but he's in the prime position to start the process.

"Powerdown" (Richard Heinberg coined the phrase and wrote the book) may well include some reversal of historical social trends: Dr Susan Krumdiek, reporting Peak Oil to the DCC, talks of "localisation", the complete opposite of the "Greater Auckland" approach so indicative of the "upside" trend.

The "market", being retroactive, has no hope of staying within touch of those receding goal posts, indeed as the Untied States has recently demonstrated, even democracy may be too slow.

War - well, better if we dodge that. No, the best thing would be a jolly fine fireside chat: Ask not what you can do to amass wealth.

As you may have noticed, that phase is over.

Ask what you can do for your family, friends, community.

He could finish with "The penny had to drop sooner or later, and I have instructed my officials to facilitate that process ..."

Of course it will never happen.

It will be: "We must grow the economy. Kick-start the dead motorbike, so we can go even faster on `reserve'."

If that is the path we go down, somebody should point out a property of the standard bell-curve graph, which starts at zero, finishes at zero and peaks in the middle: if you force the flow at the peak, you can flat-line.

For a while.

The area under the graph, though, represents the total available resource; the longer you flat-line across the top, the faster it drops off at the tail end. We have been flat-lining since 2005.

If he leaves it too long, it will be an empty-fireside chat.

Murray Grimwood lives in Waitati and writes about energy issues.