Captain James Cook thought Otago to be a ''barren, uninhabited land'' when he first sailed down the coast of New Zealand in 1770.

However, that was far from the case, as Hocken librarian Sharon Dell shows in ''Tuia - Southern Encounters''.

''It was important for me to show a Maori world-view. It's very fascinating.''

It was on his second voyage in 1773 when Cook entered Dusky Bay that he found small groups of families living there.

Unlike the northern encounters with Maori, which were deadly, Cook's southern visit was characterised by hongi, handshakes and the exchanging of gifts, she says.

That life and the wildlife of the area were captured by William Hodges, who idealised the South in a romantic way, Dell says.

Johann and Georg Forster, a German naturalist, also recorded Maori life in their journals.

''He went back to England and drew beautiful drawings of plants, birds and fish that were new to science then.

''But the plants and animals were well known to the people here.''

Maori used plants and animals not just as a source of food but to also make tools, musical instruments - an albatross wing bone became a flute - and bags.

''It showed the depth of Maori knowledge of plants, rocks and other resources.''

Examples of this knowledge are displayed in the exhibition, including the albatross flutes, kete, rock blades, necklaces, fish hooks and moa bones.

''[They] depend on a similar knowledge of raw materials and skilled makers, who imbued even everyday objects with an aesthetic beauty.''

The kete was found in a rock shelter near Puketoi Station in the late 1890s and contained hanks of prepared fibre, cords, dog skin, a whitebait net and albatross wing bones.

The fibre was from the leaves of a mountain plant, celmisia semicordata, and the 100 leaves found could have represented an entire year's harvest for trade or to make a cloak that might have taken a year to weave.

The kete shows the sophisticated textile technology that existed to strip and dye fibre and highly accomplished weaving technology.

''They knew how to go up into the mountains to get these plants and bring it down.''

Also in the exhibition are four prints of New Zealand plants made from drawings by Sydney Parkinson on Cook's first voyages and collated in Joseph Banks' Florilegium.

In the same room, Dell has hung a work by artist Ayesha Green, which was made in response to those images and one by Simon Kaan and Ron Bull, Nothing to See Here, which reflects on Hodges' work.

The explorers also created detailed maps showing safe harbours.

''This was like the first online shop - soon after the whalers and sealers began to visit and they started trading.''

There was another impact: Cook planted seeds in a small garden and brought geese to the island as well as rats. While the garden and geese did not flourish, the rats did.

''That is why on the sound tape we have the dawn chorus and then silence representing that legacy.''

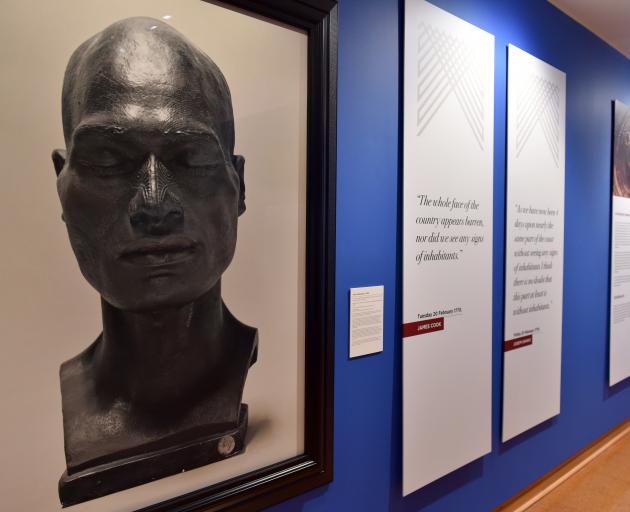

To represent the people of the time, Dell selected a portrait by Fiona Pardington of a life-cast of Takatahara, thought to have been a great chief, made in 1840 in Otago and Aunty, a 2-D facial approximation the University of Otago made using human remains found in 1939 at Wairau Bar and more than 100 archival photographs of Maori women of a similar age sourced from the National Library.

The exhibit also features the notebooks which document many of the island's place names translated from Maori phonetically.

Ngai Tahu representatives Hone Karetai and Korako signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Otago Heads in 1840 and soon after the push towards colonial settlement began.

''When the Crown did not follow up their promises of hospitals and reserves and there was not enough food a seven-generation process to get redress began.''

Dell has dedicated a room of the gallery to the documents and resources used as part of Ngai Tahu's treaty claim, including papers from James Herries Beattie, which list Maori place names along the northern and southern banks of the Waitaki as given to him by Tieke Pukurakau (1884-1925), a noted authority on Maori place names of the region, the notebook of Hoani (John) Kahu and other books and manuscripts by Maori giving details of place names, waiata and vocabulary.

''They record place names, mahinga kai practices, and an intimate knowledge of iwi history and the resources of the land.''

There is also an interactive cultural mapping tool from Ngai Tahu, which allows visitors to look at the various sites and their place names.

To see

‘‘Tuia — Southern Encounters’’, Hocken Collections, until November9.