Tom Enright is not a daredevil.

Quite the opposite, in fact, he is a firm believer in rigorous training and careful forward planning.

Which may explain why the 85-year-old is sitting in a comfy chair in his Mosgiel home, rather than having come a cropper in some of the spectacular crashes and near-misses the former pilot describes in his newly-released autobiography Many A Close Run Thing.

"I certainly learned early on that you have to be well prepared to fly a plane and know all your emergency drills, and I'm sure that's what got me through," Enright says.

"One or two of those occasions were my own fault, but mostly they were imposed upon me."

Upon returning to New Zealand, Enright was a fighter pilot and aerobatic team member, a chief flying instructor, search and rescue officer and flying boat pilot with the air force.

Those years of service included Enright walking away almost unscathed after a forced landing in his Vampire jet, which ploughed through several fences before coming to rest in a ditch.

He also had a ringside view of a near disastrous air show put on to mark the opening of Wellington Airport, took part in several hair-raising flights through storms searching for ships in distress, and navigated his way through some testing take offs and landings in Pacific waters.

During the 1959 Wellington Airport opening, a Sunderland flying boat grazed the runway with its fuselage before taking off again, an RAF Vulcan landed short of the runway and almost crashed, Enright almost planted his Vampire into the ground, and the air force display team flirted with disaster flying near Hataitai.

"I think we all regarded it as amazing that Wellington got through without at least one serious accident," Enright said.

"The idea of quitting I don't think occurred to me, but certainly as we were sitting at the take off point and observed the Vulcan come in and come so close to having a disastrous accident right in front of our eyes ... as he disappeared around the corner, `red formation cleared for take off', well you just do what you have to do and cast it out of your mind.

"I'm not saying one is fearless, but it is necessary to overcome fear to become a pilot."

Enright philosophically describes his alarms and excursions as being "simply what you had to do", but switching to civilian flying with Air New Zealand in 1971 certainly reduced the stress levels somewhat.

"I try in the book to emphasise that almost every noteworthy occasion happened in my military aviation days," he said.

"Sometimes military pilots, especially search and rescue pilots, simply have to persist into situations where no person would take a civil airliner ... Auckland harbour at 4am with winds of 85 knots blowing is not a very nice place to be, but the search and rescue pilot must go to the limit when safety of life is involved, and that is a dictum I have constantly served."

After joining Air New Zealand, Enright found himself behind the controls of what he regards as the best plane he piloted, the DC10, an aircraft he described as far more sinned against that sinning.

"It became involved in accidents, but not related to the airplane itself," he said.

"It was a lovely airplane to fly, it had beautiful tolerance and it was a pleasure to handle.

"Getting out of that and into a 747 was like getting out of a computerised sportscar and into a brand new truck, but it was some truck, the 747."

Enright's commercial flying career, which also embraced stints with Singapore Airlines and Air Pacific, may have lacked the drama of military aviation, but the challenges of getting in and out of metropolitan airports in an airborne choreography with 100 planes and one air traffic control team were still enough to focus the mind.

"I wanted the passengers behind me to be happy, relaxed and well looked after; that was a full-time job," Enright said.

"It was a different job from going down to the Antipodes Islands and photographing coves from 100 feet, so one adopts a mental attitude appropriate to the task."

Apart from one short flight in a Tiger Moth with an instructor he has not flown since, and claims to be a perfectly well behaved back seat driver these days.

"When I started navigating I was always a bit edgy about being more than a thousandth of an inch away from the controls, but I became so absorbed by the science of navigating that I was perfectly happy to relax if I had confidence in the people up front.

"The people up front are highly trained, they have to demonstrate every 180 days that they are genuinely competent, so I am perfectly relaxed about it."

Enright could not leave flying entirely behind him, though, and he now lives close to Taieri aerodrome, where he first took to the skies as a teenager.

He still pops down to the hangars, and can hear planes landing and taking off from his lounge.

"If you asked me if I would take up a flying job tomorrow if anyone offered it to me, of course I would, I would be glad to," he said.

"Yes I do miss it. It would be wonderful to go out and do that all over again."

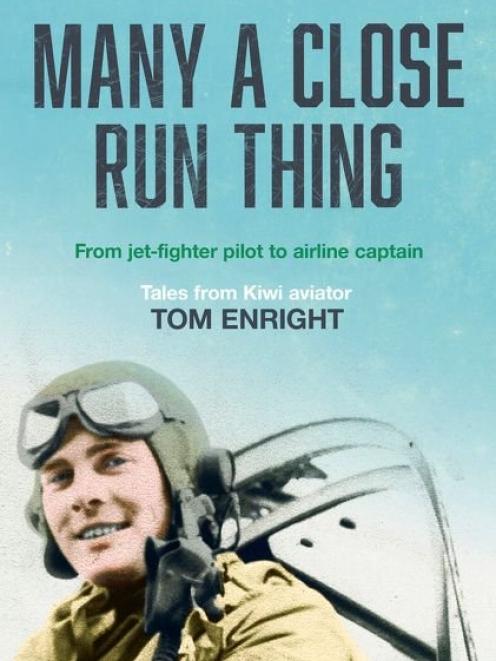

The book

Many A Close Run Thing, by Tom Enright, published by Harper Collins