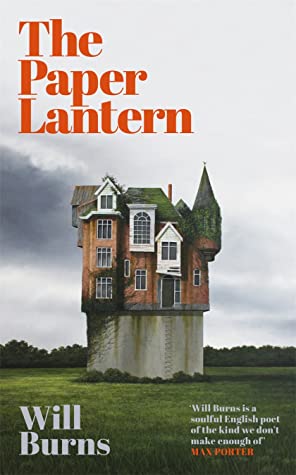

THE PAPER LANTERN

Will Burns

Hachette

REVIEWED BY PETER STUPPLES

This is a laconic, melancholic account of the first Covid-19 lockdown in Britain 2020, from the point of view of an unnamed, young middle-aged poet, living in a small market town in middle England, not far from Chequers, the retreat for any incumbent Prime Minister, and from the grand house of the British branch of the Rothschilds - symbolic sites of state power and the wealth of capital.

The lowly poet lives with his parents in their pub, The Paper Lantern. He does occasional work for them, but has a long history of part-time, unskilled employment, after failing to stick with university study in earlier years. He is a drifter, with no aims or ambitions.

Indeed, he despises those who have given in to middle-class aspirations, to marriages and mortgages.

Lockdown has closed the pub. His parents, who know no other life, have no income and no routines. The same is true for many others living ‘‘deep in the Brexit badlands’’, particularly the male, white, generally misogynistic, racist, regular customers to the pub.

Where can they now gather to rant unchallenged?

The poet spends his time walking the chalk hills around the town. He appreciates the bird life, the wildflowers, the variety of flora and fauna urgently under threat through the development of industrial and new housing estates, and, in particular, HS2, the high-speed train line being tunnelled through the chalk, joining London with cities in the North.

For the poet, the ‘‘bloated malaise’’ of lockdown is only the latest stage in the running down of cultural, social and commercial life in Britain, following the loss of Empire and industrial might, the error of Brexit - a rapid sinking into economic and cultural decline.

With his left-wing melancholia, he even questions the whole myth of ‘greatness’, the continuing rigidities of the class and education system, the very truth of the history engendered by the British elite, themselves funded by the plunder and pillage of that greatness.

Despite these strongly held views, the poet shies away from becoming involved in political action, indeed any action at all, except writing this book, which, ironically is a statement of inertia, a symptom itself of the malaise that he cannot overcome.

‘‘I understood then, in the connection I had to this place, which must be the same for everyone who lived there, perhaps for anyone who lived anywhere. Inarticulate and angry, heartsore and defeated. Caught between history and the swiftness with which the summers of our own life pass. I felt suddenly very old.’’

Despite Burns' deep pessimism, this is a finely written book, putting forward a point of view that many in Aotearoa, as well as elsewhere in our sad world, share under the shadow of Covid that threatens us all for some time to come.