Fermented foods are becoming increasingly trendy these days.

Not only do we enjoy their flavours, there is now good evidence that the microorganisms that do the fermentation and the compounds they produce are connected with physical and mental health, writes Charmian Smith.

Fermented foods cover a huge range, from yoghurt, cheese and milk drinks like kefir to fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut, kimchi and various pickles, fish sauce, soy products such as soy sauce, miso and tempeh, sourdough breads and salamis and, of course, beer and wine.

Fermented foods have been around for thousands of years, explains Prof Phil Bremer, of the food science department at the University of Otago.

''I guess originally they occurred by mistake - some lactic acid bacteria got into a camel skin full of milk and it fermented the product. Someone realised it extended the shelf life of the food - kept it edible for longer, and over time people appreciated the taste and flavour,'' he said.

The first fermented products were probably made from milk - there are about 56 different fermented milk drinks all around the world, made from a wide variety of milks. Beer is also a very ancient fermented drink, he says.

He considers the ability to preserve food, and fermentation is an important method of preservation, is the cornerstone of civilisation.

''I would argue that food preservation enabled the establishment of permanent settlements, aided exploration and travel, aided in warfare, enabled the development of large cities, because you could have food transported in. It enabled the building of large monuments - the pyramids would have been impossible without it, as people had to get their food from elsewhere and bring it in,'' he said.

Fermented foods are formed by the growth in the absence of oxygen of certain microorganisms that produce lactic acid and other compounds. Importantly, it lowers the pH of the food, which inhibits the growth of undesirable organisms.

However, some moulds and yeasts will grow on the surface of fermented food, as anyone who has left a container of yoghurt too long in the fridge will know.

''Fermentation relies on the reduction of pH, the production of acid, to inhibit the growth of undesirable organisms. Often some salt is added to things such as sauerkraut or meats, which may help set up the optimal conditions for the growth of the desirable bacteria,'' he said.

When people make a fermented food at home they often add a little of the last batch, such as a sourdough starter or yoghurt, which inoculates the new batch with the desirable bacteria.

Some fermented products are complicated with several types of microorganisms involved, he said,

''You need to understand the process and you can drive it one way or another, depending on how you do it. The byproducts of yeast metabolism are carbon dioxide, water and alcohol, so in bread-making conditions are driven towards the carbon dioxide and that's what gives it rising. In beer production you want to drive it more towards alcohol but carbon dioxide's still an important byproduct, as it provides carbonation.''

Sauerkraut - shredded, fermented cabbage, traditional in Eastern Europe and Germany - is simple to make.

''With sauerkraut, people would add something like 2% salt and then put a weight on it. When you add salt to cabbage, the salt creates an osmotic imbalance and helps draw the liquid out of the cut cabbage and that liquid contains the sugars and nutrients the bacteria needs and also helps to inhibit some undesirable microorganisms. Sauerkraut is very easy to make but you have to keep it properly covered.''

Covering the sauerkraut to exclude oxygen is important, as it prevents other spoilage organisms growing. When making it in the lab, he and his students shred cabbage, mix the salt through it, and put it in a bucket with another bucket filled with water on top to press it down, he said.

''You want the cabbage to be covered by the liquid that's exuded from the cabbage. Then we take the top bucket off, fill a plastic bag with water, and put that in the container and it forms a seal around it so the air can't get in.''

During the fermentation the bacteria produce enzymes that help break the food down, which can make it more digestible. Sauerkraut is more easily digestible than cabbage, he says.

Besides making the food more digestible, the fermentation process can produce a number of vitamins, such as folate, riboflavin and vitamin B12, and amino acids, which increase the food's nutritional value.

Scientists are realising that living bacteria (probiotics) and their byproducts can improve not only intestinal but also mental and general health.

However, many commercially made fermented products, such as canned sauerkraut, are pasteurised. That means they do not have the advantage of live probiotic bacteria, although some of the other benefits may be still there, he says.

Some fermented foods, such as yoghurt, fermented milk drinks like kefir, and sauerkraut or kimchi could be considered health products.

With others, such as kombucha, the currently trendy drink made from fermented sweet tea, it was less clear what the benefits were.

Yet others, such as beer and wine and traditionally fermented salami, which could contain a lot of ethanol, salt or fat, were not health foods but were consumed for their flavour, he said.

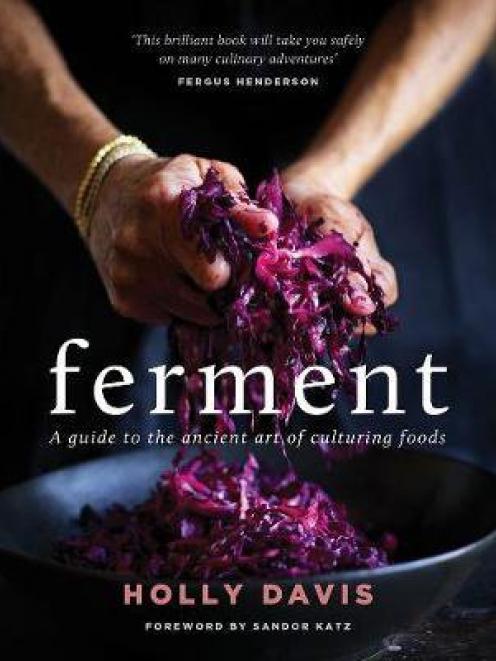

Photo: Supplied

Brined beetroot with orange and juniper

Photo: Supplied

Brined beetroot with orange and juniper

Beetroot and celery are both vastly more delicious preserved and brined as their textures provide the ultimate, satisfying crunch.

Keep the pieces fairly large in the culture as the high sugar content of beetroot increases the chances of alcoholic fermentation, which is not what we are after.

The brined beetroot can be diced and used to top soups or casseroles and is perfect with the broad bean salad or served with a cheese platter.

Makes enough to fill a 1.5 litre (6 cup) jar

Ready in approximately 3 weeks

Ingredients

1 litre (4 cups) filtered water

50g sea salt

5 celery stalks, cut into 5cm pieces (or smaller depending on your jar)

6-8 medium beetroot (beets), peeled and cut into chunks

2 bay leaves

zest of 1 orange

½ tsp juniper berries, lightly bruised using a mortar and pestle

½ tsp mixed peppercorns, cracked

Method

Bring 250ml (1 cup) of the water to the boil in a large saucepan. Add the salt and stir until dissolved. Add the remaining water, then take the pan off the heat and allow the brine to cool to room temperature.

Put the celery in the jar with the beetroot, bay leaves, orange zest, juniper berries and peppercorns. Fill the jar completely, wedging the vegetables in as snugly as possible.

Steep

Pour in just enough of the cooled brine to completely cover all the ingredients, leaving 1cm-2cm of space from the rim of the jar.

Tap the jar on a folded tea towel (dish towel) to dislodge any air pockets. Close the lid tightly and place the jar on a tray to catch any liquid that may leak out during fermentation.

Leave in a cool spot, out of direct sunlight, with temperatures around 18-24degC , for 7-21 days or until furiously bubbling. When the bubbles subside, the brined vegetables are ready to eat, but if you prefer them more sour, leave the jar out for another 1-2 weeks.

When they are to your liking, slow the fermentation process by storing the jar in the fridge. This will keep for 6-12 months.