"I can’t hammer as well as I used to," Kyle Mewburn shares.

As with a great deal that Mewburn says, this snippet is accompanied by a generous accompaniment of chortling.

"It’s terrible," she laments, comparing her two-handed technique to a woodpecker. "My building career is over."

Issues with flat heads aside, Mewburn admits to being pretty happy with the general state of things.

"It’s pretty good," she confirms.

And why wouldn’t it be? Mewburn’s a multi-award-winning author, with a new series on the go, another book she wrote 20-odd years ago looking like finally finding a publisher. She lives in beautiful Millers Flat with her wife of 34 years, Marion, in a house she built herself — held together by nails — with a grass roof.

So, all in all, plenty to be happy about.

But the contentment Mewburn has achieved is about more than these everyday metrics.

Because Mewburn is now living life as herself, her true self, for the first time, and it’s making her happy.

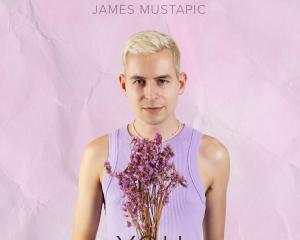

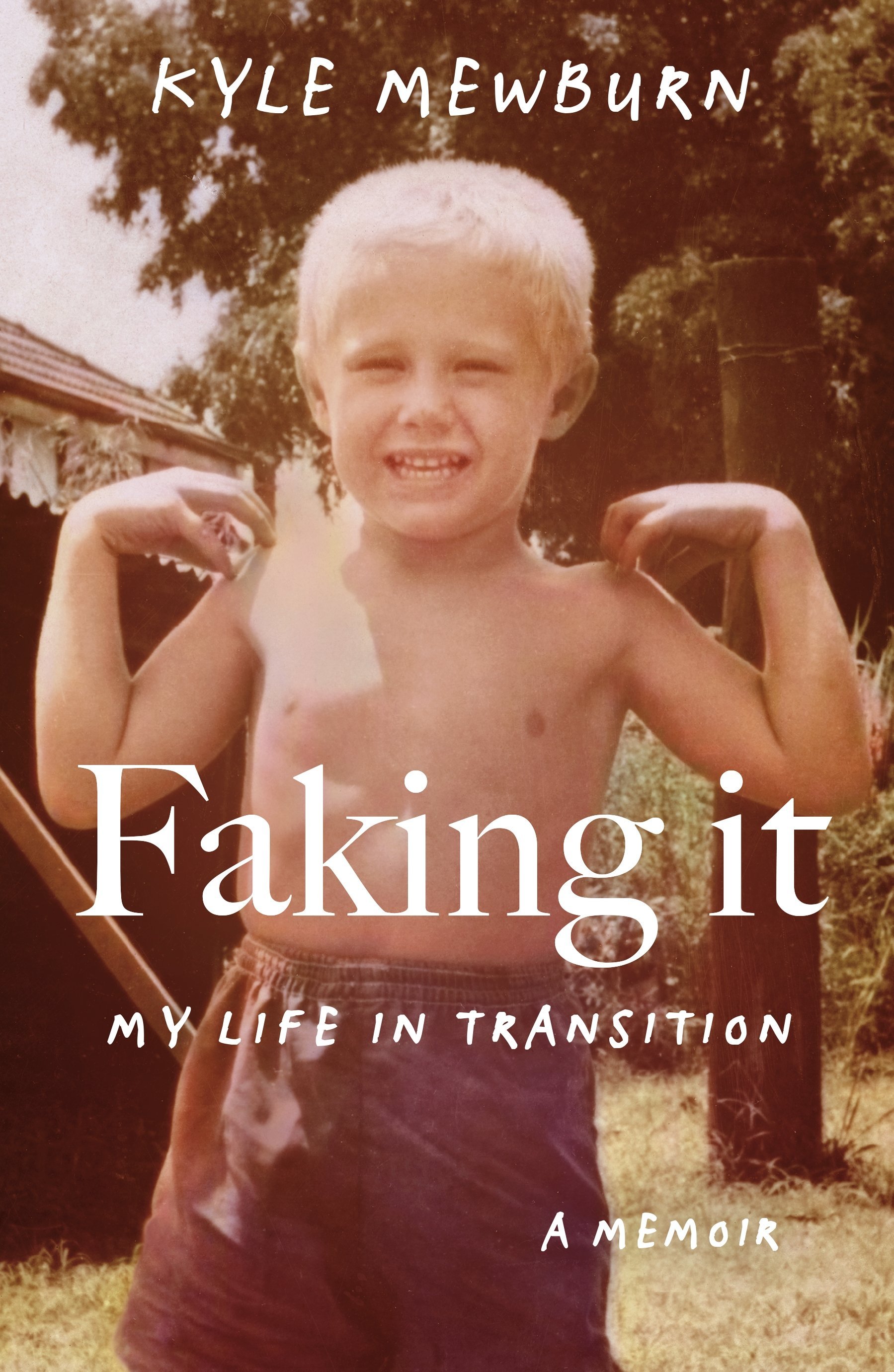

The long, long and tortuous — figuratively and, arguably, literally — road to achieving that state of being is described in her new book, Faking It, out this week.

She’s not doing faking anymore.

In her 50s, a few short years ago, Mewburn finally began the transition to become the woman she always knew she was.

Her book detailing the journey lands as discussion about what it means to be transgender is having something of a moment. Whether it’s the unfortunate ruminations of J.K. Rowling, controversies about hormone blockers, the life-affirming reality TV of I Am Jazz or the interest in the gender philosophies of thinkers such as Judith Butler and Julia Serano, the old hard-and-fast binary assumptions about gender are getting a thorough re-examination.

Mewburn herself seems slightly conflicted about stepping into that spotlight.

"Personally, I think that people should just leave us all alone and just get on with their lives," she says.

"It is not a big deal. It has always been around and we’ve always been around, some societies have embraced it and accepted it as part of being human."

Nevertheless, here in Aotearoa, as elsewhere, the recalibration to that reality is proving a struggle for some.

Mewburn offers reassurance that accepting a few more letters in the gender parade — LGBTQ etc — does not mean we’re heading for a cliff.

Her own story, as told in Faking It, lends a witty, heart-filled contribution towards that understanding.

"I think my main takeaway would be that no-one chooses to be different, or trans, or anything, or gay," she says.

"That’s who we are and it is not our fault and it is part of the human experience and people should just accept that’s reality.

"My story is about how complicated life becomes when you don’t accept that and acknowledge that and do something about it. Otherwise you end up — no matter how good your life is — being held back or separated from the rest of society by your secrets and your fakeness, just by faking it."

Mewburn’s story began in Brisbane in the 1960s, growing up in a household short on the sort of love and affection a child needs.

On top of that, the young Mewburn knew from day one that something else was not right.

Early in Faking It, she describes how she would, as a child, sneak off to her father’s workshop with a few old clothes to feel "the hem of a skirt swishing against my shins".

She was a "fake boy".

"It was a verdict that would shape, distort and warp my friendships for the next 30 years," she writes.

On the phone from Millers Flat, Mewburn says for all her success as an adult, life remained meaningless as long as she was fundamentally faking it and lying to everyone.

"To try to conceal a lie is a terrible thing," she says.

It was like the stories that circulated during the Cold War years of deep-cover Russian moles, she says, living ostensibly normal lives, waiting for the signal for their mission to begin — but it never came and they remained actors in a fiction.

For Mewburn there was also the knowledge that there are many young people facing the same uncertain crossing she faced, so sharing her story had the potential to help.

"I come from a family who have struggled with the idea of who I am but they have been willing to embrace it. So I understand how hard it is for that sort of person."

Gender, is an interesting social construct, she says.

"People like to think it is genetic and a black and white issue and, I have to admit, up to the moment when I was actually coming out myself, I was from such a binary world view — there were men and women growing up. There were just men, there were just women, that was it."

There’s a little more nuance these days.

One of the leading thinkers in this area is American professor Judith Butler, whose framing of gender as performative has been influential.

She takes as a starting point Simone de Beauvoir’s view that "one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman".

What it means to be a woman at a given time and in a given place is less to do with one’s biology at birth than the repetition of behaviours adopted from that moment that conform to a particular gender expression.

Behaving as a woman is the critical thing, the thing policed by society.

More recently, trans writer and biologist Julia Serano has posited an "intrinsic inclination model" of gender, which recognises a "subconscious sex" hardwired into people’s brains, so a child declared one gender on the basis of prenatal scans might from their earliest conscious moments know themselves to be something else.

Mewburn has a practised eye for how tightly policed this stuff is. She for decades had to know precisely how she was meant to be acting, and avoid at all costs her own inclinations.

"You have to ignore all these things you have this natural instinctive desire for or interest in," she recalls from her decades of faking.

"You have to pretend you don’t like it. ‘No, no, wouldn’t do that, I’m a bloke’."

She highlights how silly it gets: "Early on when I was out to Marion and no-one else I would drink a glass of rose on a nice summer’s afternoon and a friend of ours would say, ‘oh, you’re showing your feminine side are you?’.

"It’s wine. I like wine," she says with another chuckle.

"It’s rose. I am not coming out as anything but a rose drinker."

The Brisbane men of her childhood drank nothing but Castlemaine XXXX, she notes — making that fact alone sound sufficient reason to transition.

"It is very toxic for society and for men," she says — almost certainly meaning narrowly defined gender definitions, rather than Castlemaine beer.

It means men must deny themselves a decent cry and women are held back from all sorts of opportunities.

Being in transition and being trans meant confronting these questions in a stark way, she says.

"Where do you fit in the gender spectrum and what are you willing to do?"

For Mewburn it meant taking on quite an Odyssey, supported throughout by her wife Marion, who emerges from the book as an equally remarkable character.

The literal journey involved a trip to Argentina for surgery, recounted in some detail in Faking it, while also taking steps to adjust her body chemistry — resulting, among other things, in the two-handed hammering.

Mewburn says her formative Brisbane experience of men being men and women being women meant that when she began to transition she initially thought she needed to push as far towards the women’s side of the room as possible. She’s moved on from that way of thinking too.

"If you take a moment to look at it," she says, "there are women and men across the spectrum."

So she’s happily feminine these days but hasn’t tried to erase all evidence of the old Kyle, including her name.

"I have put in a lot of effort over the past 20 years being a best version of me and I feel like I have earned the right to retain my identity," she explains.

For some in the trans community, "passing" is the prize, which is to say, passing for the gender with which they identify.

"I came to a point where I thought, ‘I could try, but who am I trying for — change my voice, change my walk?’

"I thought, if I see myself in the mirror and see myself then that’s all that I need," Mewburn says of where she landed on the issue.

There was an element of being damned if you did and damned if you didn’t.

Trans people can be seen in videos posted online passing through life flawlessly transformed, she says, but it takes a lot of time, a lot of thought. And even then the risk of being "clocked" remains, with its attendant despair. Such moments could lead to feelings of betrayal, if people feel they’ve been lied to.

On the other hand, stopping short of "passing"carries its own costs, she says.

"I am getting people looking at me thinking," she says, and pauses. "Not sure what they are thinking, maybe they are thinking I should try harder," she says with more laughter.

"In the end I just thought, I am through with it. It is just too stressful to care."

Marion was also a very significant factor.

"I went through lots of permutations of what I could and should do and what is possible and wasn’t possible. In the end it came down to, well, the more I am me, that’s the foundation of our relationship anyway.

"Being me is what I need to be and being me is what we need to be together."

And, anyway: "I am not a Felicity."

But she is Kyle Mewburn, much-loved children’s author of Old Huhu and Kiss! Kiss! Yuck! Yuck! and many, many other titles.

It raises another question. She has been thinking about the answer.

"I am always faced now with almost a sense of obligation that stories should include diverse characters.

"You do have an open mind about it," she says, "but stories seem to write themselves. Anything that is contrived, kids can see contrived stories from a mile away. So, as long as it is a sincerely honestly told story then fine.

"One book at the moment has what you might call a pansexual. It’s not actually human so I might be fudging a bit.

"But even I find it difficult writing some things like that, with the pronouns. You have to go ‘they’ all the time. Complicated."

"An early series of mine, I was told by a lot of teachers, boys wouldn’t read because the covers had a little pink on them," Mewburn says.

There are other ways to get young minds thinking.

Mewburn says her Dinosaur Rescue books involve a boy who is different. Not gender different so much, but intelligent and different.

"Often my stories have this notion of being different, outside of the box. So not necessarily a focus on gender but focused on feeling different and finding your place. Which has been one of my themes, and in a way exploring my own self — but without giving myself away of course."

She no longer has to worry so much about giving herself away, and has been pleasantly surprise at the level of acceptance she has encountered.

The overwhelming majority of people around Millers Flat have been fine, she says.

"I am blown away by the level of acceptance and support. Everyone is being amazing."

Well, maybe not everyone.

"But 99% are being at least accepting. I haven’t had any pitchforks and flaming lanterns."

Her experience of the wider world is that as soon as she starts talking to someone, anxieties about otherness seem to melt away.

"You see that and you think maybe the world is changing. And of course you read about other places in the world and there is still a high suicide rate among trans youth, there is still a massive amount of bullying and terrible stuff happening. Murders. So you then think it is only my little bubble, which I am happy to be in."

Mewburn describes that bubble in Faking it. There’s a social occasion. A couple of guys stand apart to talk about something, maybe football, maybe building. But who cares? Because she’s not going to join them. She finally feels she can join the women’s circle, champagne in hand.

"It felt good," she writes.

"And just incredibly, heart-warmingly right."

The book, the talks

The Dunedin Writers & Readers Festival runs through the weekend. Kyle Mewburn is involved in two sessions at Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

The Books that Made Me

Today, 2pm-3pm, with Rose Carlyle and Nalini Singh.

Writing for children

Tomorrow, 1pm-2pm, with David Elliot and Robyn Belton.

Faking It, (Penguin Random House), is out this week.

Auckland Writers Festival: Sunday, May 16, 12.30-1pm, "Family dynamics" with Charlotte Grimshaw and Lil O'Brien.