Dunedin’s soldiers faced many difficulties returning to civilian life following World War 1; difficulties often explained by poor management on the part of the very authorities working to assist them, Clare Sullivan writes.

"Since my return I have been very much impressed with the evidence of the prosperity of the people. Small struggling `cockies' have become motor car-owning farmers, and in place of the old two-room cottage with the lean-to at the back, I have found all sorts of bungalow additions. I was told of great prices of butter-fat and wool, and all-round good times ...

"Everything speaks of prosperity. Now all this is just as it ought to be and I was really glad to see it, but it suddenly occurred to me where do I come in? Where is my motor car? What have I had out of high war prices? I have the feeling I have missed an opportunity. The war is now over, and I am told that the lean years are coming, but I have had no share in the fat years ...

"After thinking it all over I have come to the conclusion that if I had got married and dodged military service as long as I could, I might have had my car and bungalow to-day.''

The above constitutes the majority of a letter written to the Otago Daily Times and published on January 8, 1919, from a returned soldier who signed themselves simply as "Main Body''. The letter received two responses.

The first came from a member of the public who signed themselves, "Ashamed''. They wrote, "It seems to me that no honest patriot could read that letter without a blush, remembering what was said in 1914 and immediately following to the soldiers and knowing how truly `Main Body Soldier' states the position ... It seems to me most reprehensible, in a prosperous country like this, that we should offer these soldiers a small temporary pension, and then turn them loose.''

The second response came from another returned soldier, "Digger'', who wrote to support "Main Body''.

"Of course, it is very pleasant to see everything going so well, but why should we, the returned soldiers, not share in the general prosperity?''

He goes on to explain an encounter with a farmer when looking for property to buy. When asked about a property nearby, the farmer , oblivious to the fact he was a returned soldier, replied, "that place is under offer to the Government, it is no good - a regular swamp; it is only fit for soldiers.''

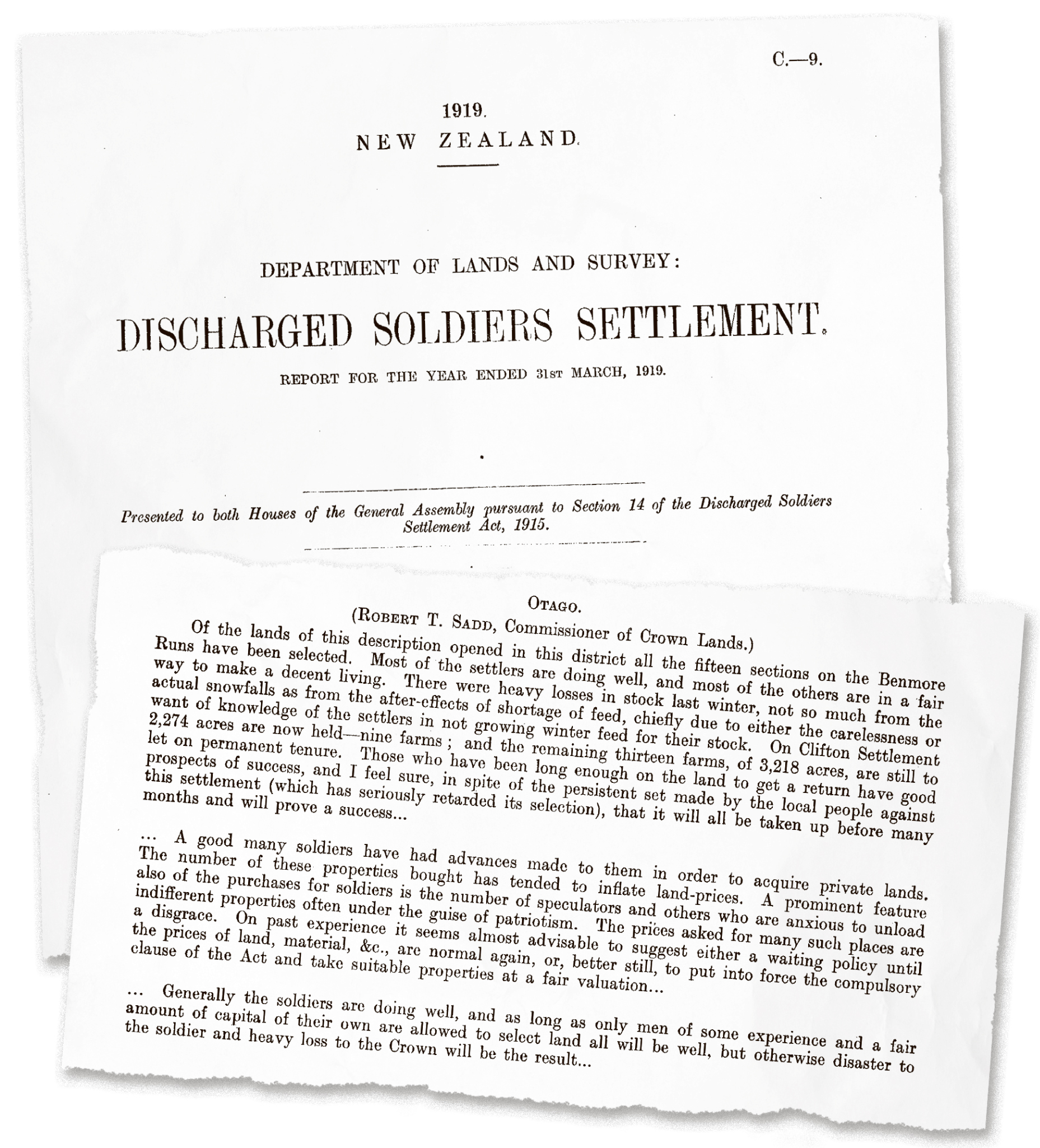

Obtaining good, workable land does not immediately spring to mind when one considers the difficulties soldiers must have faced upon their return to New Zealand. In 1919, however, Soldier Land Settlements was an issue of prime contention.

The New Zealand Government introduced Soldier Land Settlements across the country as an added incentive for soldiers to return. However, the scheme proved to be a disaster, and the Otago Settlements are no exception to this description. The soldiers had fought for their country. It seemed only just that they be provided with a means to own their own land upon their return.

The Government purchased land to lease out to soldiers looking to establish themselves in agriculture, and gave them the opportunity to eventually buy the land for themselves. In addition, they gave the soldiers capital with which to set themselves up. In theory, this made for a promising scheme. After the war, however, the Government failed to execute it successfully.

The scheme was the first designed to assist soldiers on their return to New Zealand. The Government, frantic to provide enough land for the soldiers, paid excessive prices for most of the properties acquired. In many cases, the quality of the settlements was inadequate and soldiers were left struggling to raise enough to cover the excessive rents.

This was the case at the Clifton Settlement: "The rental of one particular block ... was very high, involving a payment of something like £71 for the first half-year, and on such a basis the soldier settlers were not given a fair chance.''

While this settlement was initially unimproved land with no fencing or housing, the Government purchased it at a rate reflecting neighbouring properties where fencing and housing were included. Furthermore, the sections were far too small for settlers to make a good living.

It placed soldier settlers on the back foot from the very beginning.

The Clifton Settlement was opened in March 1917. By the end of July 1919, the Clutha Leader stated that of the 10 soldiers who had settled, three had already abandoned their sections.

AS EARLY as August 1919, the Returned Soldiers Association had produced a comprehensive report on the grievances of the soldier settlers: "The soldier settlers at present each have to build his own shed, yard, dip, etc., beside part fence, build his house, stable, and shed, and purchase his stock, implements, seed, etc., out of the handsome sum of 750, which this committee, and soldier settler, frankly admit cannot be done.''

Despite this, the Government still expected that soldiers would pay their rent on time: "a soldier has been harassed by letters, evidently from the local Land Board, pushing him for payment, when it is perfectly apparent to the Commissioner that the man has nothing.''

At Clifton, the defining factor in determining the success of the soldier settlers lay in the extent of their own private capital. Those who could draw on their own savings rather than have to rely on the £750 starting capital from the government were less likely to give up trying.

The Benmore Settlement was no better. While rents were not as demanding as at Clifton, because the Government already owned the land, using this land as a soldier settlement sparked great debate.

The government had been warned from the outset of the poor quality of this land, much of it being low-lying and susceptible to being covered in snow so thick sheep could never survive.

One person, who signed themselves W. E. Stevens, had written to Parliament detailing his extensive knowledge of the unsuitability of Benmore as a settlement. In that letter, Stevens made mention of the loss of "about half a million sheep'' in 1895 and the fact that in 1903, snow fell in July and remained at a depth of 3ft (1m) until September. In January 1919 Stevens wrote to the Otago Daily Times: "it seems unbelievable that any body of men could be so foolishly incredulous as to my statement of facts, and, in spite of such evidence read out to them, could do such a cruel thing as to put these settlers on such country, where disaster was bound to overtake them before many years.''

The land provided to soldiers at the Benmore Settlement was poorly subdivided and soldiers were left with no hilly pasture on which to keep their sheep safe when the flat land was covered in snow.

One settler at Benmore, Mr Williams, described his situation in June 1919 to Mr. R. T. Sadd, the Commissioner of Crown Lands: "his section was swamp land and would have to be drained. It was intersected by small creeks in which he had lost 150 ewes, although he had built numerous bridges.''

The RSA committee, which produced the report on Soldier Settlements in August 1919, stated "that the granting of runs similar to Benmore, which is 40 miles from a rail-head and on bad roads, and generally unsafe country for sheep, is nothing short of suicidal''.

The Government refused to acknowledge its shortcomings in this regard for a long time, placing the blame squarely on the lack of expertise on the part of the soldiers. In fact, it took until 1920 for the Land Board to acknowledge the poor subdivision at Clifton.

Unfortunately, the soldiers' difficulties were not confined simply to Land Settlement. A major issue towards the end of 1918 was the case for retrospective allowances. In 1917, the Government decided to increase the rate of pensions and allowances given to the soldiers and their dependants. These increases however, were initially only made effective from January 1, 1918, and thus only applied to those soldiers entering camp after that date.

THIS decision met an incredible outcry on the part of the Returned Soldiers' Association, demanding that these increases be made retrospective, to be fair to those soldiers who had given their service since the beginning of the war.

"The association maintains that it is utterly inequitable that the men who offered their services without first demanding the settlement of conditions should be worse treated than those who insisted on definite conditions before entering the camp.''

Pressure on the Government mounted until its hand was forced to make these increases retrospective.

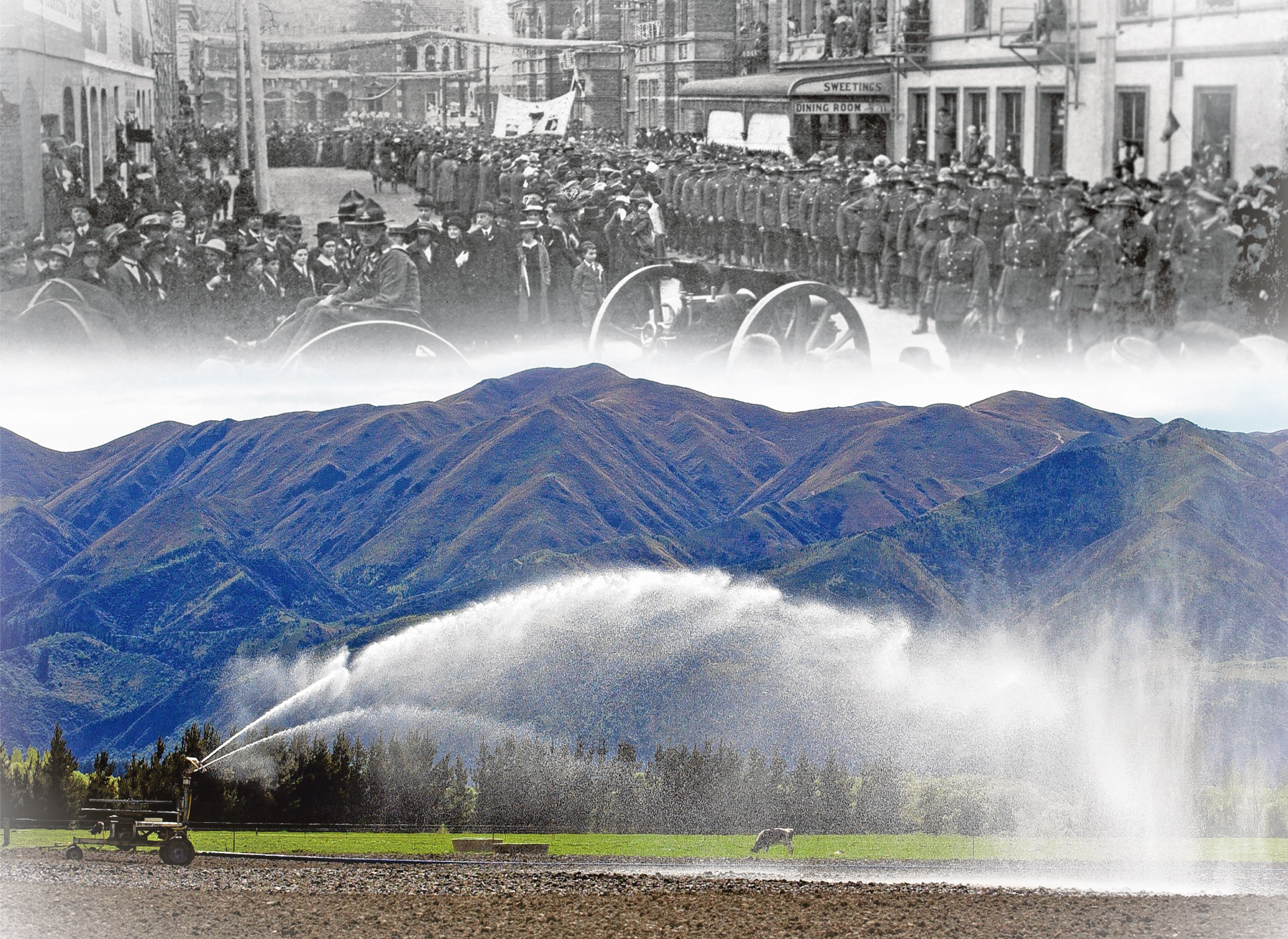

In spite of all this, the soldiers were still treated as heroes by the Dunedin public.

In February 1919, a Mr F. Duncan donated "a crate of Ettersburg No. 80 strawberries'' and "an ample supply of cream'' to the soldiers receiving treatment at Dunedin Hospital.

Sweet Pea Day in January 1919 and Chrysanthemum Day in June 1919 served as fundraisers for the Returned Soldiers' Memorial Club Building Fund, where the public donated fresh flowers to be sold for the cause. Sweet Pea Day managed to raise a sum of £421 for the cause, despite "rather fickle'' weather.

In its coverage of the Otago Winter Show in June 1919, the Otago Daily Times stated "as has been the case for some years past, the show is again furnished with a number of organisations which are devoting their energies to raising money in the interests of the soldiers''.

The war may have ended, but the support of the Dunedin public for the soldiers persisted.

Even as late as a full year after Armistice Day, Dunedin soldiers were still battling against unfair treatment in the process of their repatriation.

Many soldiers returned injured, requiring medical treatment for months following their return. In these cases, they remained employed by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and received a total of nine shillings a day. These soldiers would only be discharged when their medical condition could be assessed by Military Medical Boards. Once discharged, they would receive a pension of 22 shillings per week and be expected to seek employment to make up the difference.

In November 1919, however, many Dunedin soldiers were discharged from military service while still receiving regular medical treatment. Their conditions and the medical treatments needed made job-seeking difficult as few employers wanted to hire men unable to complete a week's work.

The case was taken up by the RSA, which decided to withhold information relating to specific soldiers' cases from the Minister of Defence, Sir James Allen.

This was done to present them with greater impact at a general public meeting in protest of such treatment: "At the last monthly meeting things came to a head, and the large gathering of members, after going thoroughly and sanely into the matter, decided it was high time the public was given an opportunity of seeing how the men were being treated.''

This sentiment meant the meeting continued, despite the declaration from Allen that "some of these cases apparently deserve reconsideration, and were it necessary to do so, I would ask the commandant to suspend their discharge from the E.F. pending inquiry''.

The public turned out in full force to attend, "the seating accommodation upstairs and downstairs being fully occupied.''

The public's support of the soldiers was emphasised by the Chairman of the Repatriation Board, Mr James Begg in his address "when such a large public meeting of citizens could be got together by the Returned Soldiers' Association a year after the cessation of hostilities, it showed that the people of Dunedin were determined to see that the right thing was done by their returned men''.

It appears from the coverage throughout 1919 that the difficulties the soldiers faced following their return, with regards to land settlement, retrospective financial assistance and inappropriate discharges, occurred due to poor management on the part of various government departments.

The public, however, remained steadfast in their support of their soldiers and firm in their determination to demonstrate their gratitude.

Clare Sullivan wrote this piece as a University of Otago humanities intern at the Otago Daily Times.

Comments

Brilliant! Author!

Desk job wallahs - tricky Johnnies. Reserved workforce, not a tinker's cuss for the struggling veteran.

Later, in W2, iwi lost their men overseas. The Maori Battalion were on the frontline. On return, the same old second class citizenship prevailed. You've got to wonder why.