Energy is the stuff that makes everything work, and New Zealand has certain advantages when it comes to generating it. But we need to do better and research led by the University of Otago's Centre for Sustainability points the way. Tom McKinlay reports.

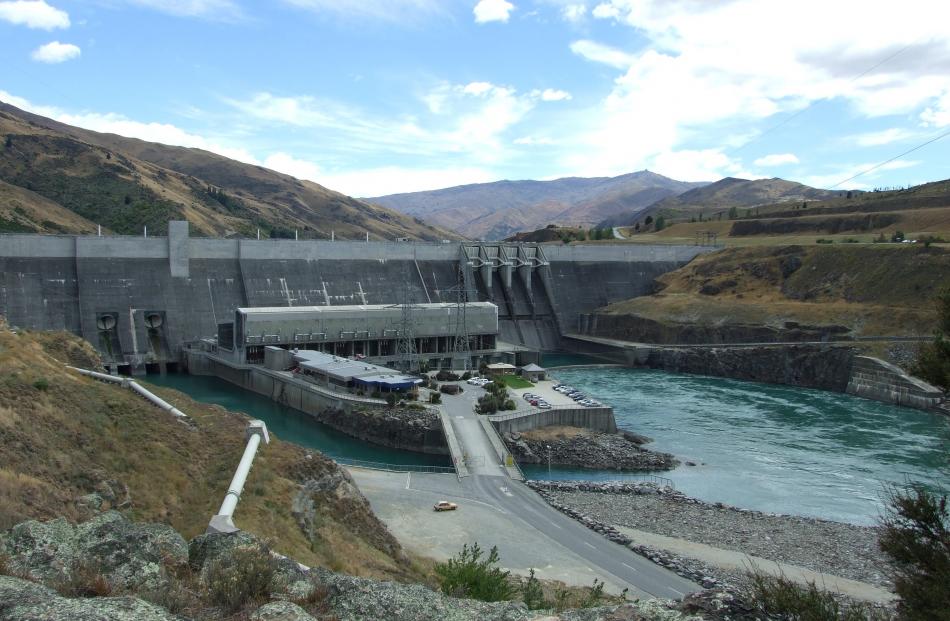

We will tell anyone who will listen: 80% of our electricity is renewable.

Few countries in the world do any better than that. Not quite 100% pure, but not bad. Scratch the surface though, and the nation's relationship to energy starts looking a little less exemplary, a little less world leading. Our houses leak heat and our transport systems, and much of our industry, are hooked on hydrocarbons.

The University of Otago's Centre for Sustainability has been doing more than scratching surfaces. It has dug deep into our relationship with energy and this week released 10 policy briefs from its ''Energy Cultures'' research.

It's work was funded by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and set out to answer a couple of questions: Where are the ''highest impact'' opportunities for energy savings in our homes, businesses and transport?

And in transport, what is possible with new technologies and energy efficiency practices, and how can they be encouraged?

The policy briefs race across the landscape of energy use in New Zealand. Looking at fuel poverty, energy use in small and medium-sized business enterprises (SMEs), eco-innovation, electric vehicles (EVs), efficient driving, urban freight, generation Y and transport more broadly.

The centre's researchers approached the questions using an ''energy cultures framework'', which views our energy use in the context of ''norms'' and ''material culture''. The former is about what we regard as normal behaviour in relation to energy use; do we regard it as normal to live in a draughty house and drive a poorly tuned car in an erratic and inefficient fashion? Material culture is those assets: the house and the car. What we regard as normal and the state of our assets has a significant impact on how we go about using energy - our practices - according to the policy briefs.

''If we are looking at change, it is always going to be a combination of technology change and the change in what people do,'' lead researcher and Centre for Sustainability director Prof Janet Stephenson says.

''But those things can be held back by people who have locked in cultures of behaviour: whether you are a business that is just used to doing things a certain way or households used to doing things a certain way, you get locked into these patterns. That's what we call cultures.''

So, yes, a good bit of our electricity is renewably generated, the product of mountain-fresh rivers cascading through proud hydroelectric installations, but many of us use it less than efficiently. Because that's part of our culture too.

Take housing.

The study found that ''much of New Zealand's housing stock, particularly older houses, is of low thermal quality''. They are cold and damp and hard to heat, and as a result bad for your health and wellbeing.The policy briefs quote a familiar parade of home heating experiences: ''We had guests over and their noses had turned blue and we said right it's time to do something about this because this is embarrassing,'' commented one respondent to the centre's surveys.

''It's very cold and damp in this house ... you can actually feel the draught coming in through the windows ...'' said another.

These are our norms now. But the centre's research highlights that householders can easily improve the efficiency, warmth and comfort of their homes: improve the material culture.

Solutions are available, many of us simply don't apply them, even when they are cost-effective: they have not yet become normal behaviour. Meanwhile, that clean-green electricity is wafting out the window.

There are many reasons why getting to grips with our energy use is important, says Prof Stephenson. Among them, the enhanced health and wellbeing that flows from better insulated homes and the much improved contribution to the international effort to cut greenhouse gases we could make if we tuned our cars and drove them more efficiently. That's important because our 80% clean-green electricity isn't even half the story.

''Only around 40% of all energy used in New Zealand is renewable,'' Prof Stephenson says.

''So around 60% of our total energy use is fossil fuels: coal, oil - mainly petrol and diesel - and gas. We tend to conveniently forget this when we talk about how clean and green New Zealand is, and just focus on the electricity story.''

Major change is required to move away from the fossil fuels used for transport and in industry, she says. A clean energy future is not just about switching to renewables, it's about using all energy more efficiently, so it takes less energy to do the same amount or more work.

The better news is that we are as a nation ready to get on board the energy efficiency wagon, the centre's researchers found. More than 65% of respondents to a survey said New Zealand should reduce the amount of energy we use. Overall, the researchers use. Overall, the researchers found majority support for ''radically'' changing the way we produce and use energy by 2050, and a desire for warmer homes, affordable energy and sustainable or renewable energy.

There's a strong desire for Government leadership, Prof Stephenson says. The Government has tended to let the energy situation just chug along, driven by market forces, hoping for the best.

''It is now clear that we are not always getting the best outcomes by just letting things chug along: sometimes because the market is not working as well as it should, and sometimes because there has to be complementary measures.''

An example is the emissions trading scheme, the signals from which are insufficient to change transport fuel use, as the impact is just two cents a litre.

''It is not going to make you buy a more energy efficient car,'' Prof Stephenson suggests.

There needs to be other complementary measures to drive the change.

That's particularly the case when patterns of behaviour, culture, are being reinforced by things outside someone's control. For example, it might be difficult to break out of a pattern of driving to work unless there's a good alternative; perhaps public transport or cycle lanes.

''The key message here is that you have to look at both things. You have to look at the cultures of the group that you are trying to work with, but also look at those things outside of their control that can be tweaked or changed in some way to make that change possible,'' Prof Stephenson says.

Back to those cold, draughty houses then: what's to be done? There are ''norms'' to be overcome. Some of these may sound familiar: having ''low expectations of warmth'', ''maintaining traditions from upbringing'', and regarding it as a ''luxury'' to heat the kitchen.

The researchers found that, among other things, simply experiencing another house that was warmer as a result of improved insulation could start to shift what was regarded as ''normal''. Getting good independent information was another important factor.

Of course, being able to take steps to improve insulation or upgrade inefficient household appliances is beyond the reach of some, particularly people in rental accommodation on low incomes.

The research identified that 35% of New Zealanders had either gone without power or spent more than 10% of income on power, or both. There's a policy brief dedicated to fuel poverty, which recommends thoroughgoing policy action to strengthen requirements for rental properties to make them fit to live in.

''It does require the market working better, so the right signals getting to landlords about what is acceptable and what is not,'' Prof Stephenson says.

That's what happens in most developed countries, she says.

Several of the 10 policy briefs relate to transport, not least because cutting energy there is one of the best ways for us to cut our collective carbon footprint.

''While the Government's policy on electric vehicles is focusing on their target of 2% of the fleet being EVs by 2021 or 2022, the question is, `what about the other 98% of the fleet?' and how do we start addressing that aspect of it too?'' Prof Stephenson asks.

Achieving the EV target would represent only a 0.18% reduction in New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions.

There need to be other initiatives that will address energy efficiency.

Efficient driving, for example, can improve fuel economy by up to 45%. But of the dozen ''efficient driving behaviours'' the researchers identified, 10% of drivers do none, and hardly anyone does most of them. So why not include efficient driving practices in driver licence testing to make it the norm? The centre's researchers think we should.

There are certainly some bright spots on the horizon. The norms, material culture and practices of Generation Y herald an altogether more sustainable transport future.

The centre's research has identified that the private car is not the default transport option for Gen Y. Rather, their norm is to mix it up. Their material culture involves the bus pass, bicycle, skateboard, raincoat and walking shoes, or a smartphone for virtual travel. As a result their practices are low carbon: they are conscious of that.

The centre's policy recommendations from the Gen Y research include creating an 18+ ID card, as an alternative to a driver's licence, and investing in infrastructure that supports the spread of multimodal transport.

Carbon emissions is the imperative driving much of this.

''There is a bit of a finite window there, especially in respect of our use of fossil fuels,'' Prof Stephenson says.

By the second half of the century the world needs to be carbon zero. That's a little more than 30 years away, and given that infrastructure, such as roading, can be expected to last longer than that, good decisions need to be made now.

''Actually, New Zealanders are already seeing these things as important,'' Prof Stephenson says.

''New Zealanders are quite clear on what they want, where the changes should occur, it is just that they are not seeing them happen fast enough.''

Following their launch, in Wellington this week, the 10 Energy Cultures policy briefs are now being fed into the Government's decision making nodes, they are in the hands of the ministries with an interest in transport, and will be a submission on the Government's draft New Zealand Energy Efficiency and Conservation Strategy through to 2022.

They may yet inform a new normal.

Comments

One of the biggest problems with improving rental accommodation is that investors in housing buy low quality houses and rent them out with minimal upgrade. There are no laws requiring minimum standards of insulation and heating so the tenants suffer. This touches on the biggest social problem in New Zealand in that tenants have no security of tenure and are always losing their home and having to move even though they pay the rent. This often means children changing school and people having to change jobs. This is very disruptive to family life.