Whether it is the price of petrol or the revenue-gathering activities of speed cameras, motorists are a vocal lobby. It was ever the way, writes Associate Professor Alex Trapeznik.

Cave Rock is made of toffee

And the sea of lemonade

And the little waitress wavelets

Are always on parade

When cars roll down to Sumner

On a Sunday

So wrote motoring writer Denis Glover. It might be objected that by ''cars'' he meant tramcars, not motor-cars, but among his other literary endeavours Glover was editor of Motoring, the official organ of the Canterbury Automobile Association. This was just one of a surprisingly large number of New Zealand motoring magazines that appeared in the 1920s and '30s.

The earliest motoring journals were purely commercial enterprises, the most successful of them produced by Arthur Cleave, an Auckland periodical publisher and early motorist. Founded about 1903, his New Zealand Motor and Cycle Journal claimed to be ''the oldest wheel paper in the southern hemisphere''. The journals published by motor clubs contained a wide range of motoring and technical news and advice, along with reports on car and motorcycle competitions, touring and holiday destinations.

Though they covered questions of motoring legislation, taxation and road construction, most steered clear of any overt political line.

However, almost from the start, motorists exerted influence on local and national government via their clubs. The first decades show patchy successes and a complex picture of shifting alliances between automobile associations and other special interest groups; such as local government bodies, promotional leagues, tourist organisations, commercial vehicle operators, and cycling and motor sports clubs.

They were successful enough that by 1925 the editor of New Zealand Motor Life, the official organ of the Auckland AA, felt the automobile ''associations have more than justified their existence. They have watched affairs on behalf of the motorists ... and have by persuasion or agitation had many anomalies removed, and many wrongs righted. They have ... helped in the promotion of beneficial legislation for motorists, and ... have helped the local authorities to keep abreast of the times.''

From 1903 on, regional motor clubs were formed throughout the country. By 1915 there were 11 and by 1928, 15 associations.

From the outset, they co-operated with one another on matters of common interest, but there was no single national organisation until 1965. A motor union was formed to co-ordinate the activities of the South Island clubs in 1920, and a northern counterpart was set up in 1928.

Though they had a political agenda and several adopted the name ''automobile association'', the New Zealand clubs were not explicitly campaigning organisations on the model of the AA in Britain, which employed road patrols to warn motorists of police speed traps and took other direct action against what it saw as official harassment. Speed traps seem not to have been frequently employed by the police in New Zealand, and magistrates in general were not seen as being unreasonably harsh on motoring offenders. Local motor clubs saw no need to institute road patrols until the 1920s, and even then they were intended to maintain road signs and help stranded motorists, not warn of any police presence.

However, the patrolmen could on occasion not resist warning motorists of speed traps. In 1925 a committee member of the Otago Motor Club stood in the middle of the road near the Dunedin Botanic Garden to warn motorists heading up North Rd that there was a police speed trap nearby. He was reported and charged with obstructing the police. The magistrate rejected his defence that he merely sought to prevent the commission of an offence and fined him £10.

Not all judges took traffic offences so seriously. One Auckland magistrate, an enthusiastic motorist himself, asked a policeman giving evidence in a dangerous driving case about the location of the speed trap. On being told, he replied, ''Thanks, it's just as well to know.''

In general, though, motor clubs co-operated with the police and local authorities in policing dangerous driving by both their own members and other motorists. The secretary of the Otago Motor Club would write them a stiff letter reprimanding them, or, in more serious cases, invite them to account for their behaviour in person. In 1913, when some Evansdale schoolchildren threw stones at passing cars, the motor club's secretary sent a letter to their headmaster, saying: ''As this is certainly a serious practice, should the children not be checked in time I would deem it a favour if you would warn them against such a practice''.

Motorists' clubs were acutely aware of the importance of public opinion towards the ''cause of motoring''. Most retained a lawyer to defend cases against members where a principle was seen to be at stake. Club officials also lobbied government ministers on behalf of members. The Minister of Justice received a steady stream of complaints regarding prosecutions for motoring offences, but always replied politely that he could not intervene in the workings of the courts.

Some clubs saw their main purpose as social. They organised regular runs to local beauty spots for picnics and recreational activities such as motor gymkhanas. These were charitable events that combined light-hearted driving competitions with prizes for the most attractively decorated vehicles, and some clubs organised long-distance reliability runs.

Motor clubs were in regular contact with urban and rural councils regarding the state of roads and bridges, and were often sufficiently well funded to be able to subsidise building and repair. Their members were not above occasionally contributing their own labour as well. Nearly a hundred members of the Southland Motor Association laboured on the improvement of the six-mile (10km) road from Invercargill to Oreti Beach in 1923, and a few years later on the road to Bluff, 14 miles away. This sort of mucking-in was most unusual in international terms.

When clubs wished to influence local government decisions, they often sent delegations to the city or county councils. One such approached the Dunedin City Council in 1915 asking for ''more equitable treatment between motors and other vehicles''. By this, they usually meant imposing regulations to which cars were subject on other road users as well. Lighting for bicycles and horse-drawn wagons was a regular demand, against which it was argued that if the car drivers slowed down and drove a bit more carefully, the lights would not be needed.

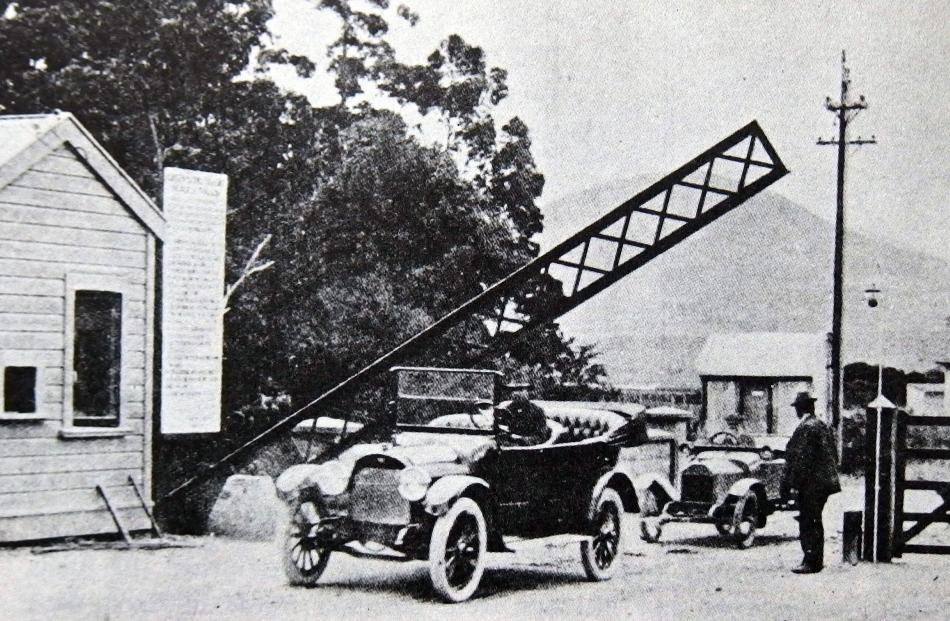

When clubs were unable to convince local councils to change their bylaws they would sometimes mount legal challenges. For example, when a tollgate was placed across the main highway by the Green Island Borough Council in 1915 to recoup the cost of road repairs, the Otago Motor Club raised £75 from its members to take the council to court (this would be equivalent to more than $10,000 now).

Motor clubs also maintained close contact with their local members of parliament and were frequently asked for information on proposed legislation likely to affect motorists. For instance, when in 1914 changes to motor vehicle taxation were under consideration, the Otago Motor Club sent the minister in charge of the Bill a list of formal recommendations, copies of which were sent to the local MPs. In the event, the effort was wasted, as the Bill was dropped because of the outbreak of World War 1.

The war made the private car appear a symbol of unpatriotic luxury, so the motoring organisations did their best to pre-empt criticism by raising funds for patriotic purposes. Within weeks of the outbreak of war, the Otago Motor Club had raised £274 from among its members to pay for two cars to accompany the expeditionary force (this was the equivalent of more than $40,000 today). They also offered a fully fitted-out ambulance to be sent to the front, and gave their own services as drivers in the motor volunteer corps. This scheme had begun badly in 1909 when an officer was killed in an accident caused by his drunken volunteer driver on the way to exercises outside Christchurch. However, by March 1915 the volunteer motor reserve comprised 133 officers.

As the war progressed, motor club members helped transport convalescent soldiers and took them on sightseeing tours and trips to the theatre. When their interests coincided, motor clubs collaborated with non-motoring special interest groups. The Otago Motor Club, for instance, co-operated with the Otago Expansion League to promote new roads to improve tourist access. In 1912 it badgered the government tourist department to get a road built to the summit of Flagstaff, but the department offered to pay for a shelter hut instead.

Before World War 1, motorists were inclined to believe resistance to their demands was based on ignorance of the benefits of motoring and hostility to motor vehicles would fade once those in influential positions acquired cars of their own. For instance, Balclutha motorists campaigning to have a rural road widened concluded that ''it seemed that the only way to get the road opened would be to wait till the [farmers] had cars of their own and then they would change their minds''. In parliamentary debates before the war, politicians would often refer to having been passengers in friends' or constituents' cars, but only a few had their own. However, by the late 1920s most MPs had cars, and debates on motoring questions were consequently much better informed.

At local government level, few councillors had taken to motoring by the start of World War 1. In Dunedin, for example, in 1914 the mayor did not have a car, official or otherwise. But by 1924 almost a third of local politicians were motorists.

This was about three times the rate of car ownership of the population in general.

This level of familiarity with motoring on the part of members of local and national government affected how the motor clubs were viewed. Initially, their expert opinion was sought and their advice often adopted. During the inter-war years, however, they were increasingly seen as special interest groups and their claims treated sceptically. And as car ownership spread, they became less representative of motorists in general.

Even Sir Joseph Ward, the Southland MP who had been an early proponent of motoring, had become more wary by the late 1920s. When as prime minister in 1929 he was approached by a delegation on the question of funding the Main Highways Board, he was, according to one report, ''very short and curt in his opening remarks, and gave the impression that he considered the Deputation was the result of political propaganda''.

His attitude softened when he recognised one of his constituents among the delegation, and he then gave ''an opposite and entirely satisfactory answer'' to the delegation's request to honour the previous administration's undertaking to devote taxation revenue from motorists to road construction.

This was a very touchy subject. Winston Churchill's name was forever mud among British motorists because he was blamed for the Treasury's ''raid'' on the Road Fund in 1926. When in 1929 the New Zealand Government followed suit, its action prompted strong combined protests from motoring organisations, chambers of commerce and local authorities, but the Treasury finally got its way in 1931.

As this suggests, the effectiveness of political lobbying by motor clubs was uneven. Their campaigns could come to nothing if they were opposed to the government's financial interests.

One long-running campaign involved attempts to have roadside advertising hoardings removed, on aesthetic and road-safety grounds.

The growth of motoring was thought largely to blame for the spread of such advertising, as much of it was for car-related products and services. Pressure from motorist consumers was therefore expected to be most effective. The principal owner of hoardings, however, the government Railways Department, stood firm. Motor transport was already eating into its passenger revenue in the early 1920s and it wasn't going to let the motorists take away this source of income as well.

The campaign initiated by the motor clubs had some initial success. The larger oil companies agreed to remove roadside signs wherever there were objections to them. Yet in the early 1930s the signs began to reappear.

New Zealand motorists were well aware of the American and British anti-billboard campaigns from newspaper reporting. The New Zealand press supported what was seen as the local manifestation of an international campaign by reprinting many stories about the excesses of roadside advertising in the United States, as well as in Britain and even Italy, where the Fascists banned it outright in 1938. The Press, in Christchurch, urged automobile associations to become ''the unofficial protector[s] of country roads'' from the ''unconscious vandal''.

The early campaign focused on areas of natural beauty where signs had been attached to trees and bridges or painted on rock faces. Firms that supplied motorists were the most susceptible to pressure, but the line taken by motoring organisations could be undermined by their journals' reliance on advertising. The official journal of the South Island Motor Union carried large advertisements on its front cover in 1929 depicting roadside signs for Big Tree petrol. One showed the firm's name painted on a large boulder with the caption, apparently not intended ironically, ''Do you know where this is?''.

Local beautifying societies approached motor clubs for their support in the campaign. The clubs lobbied their members of parliament to support legislation to allow county councils to ban roadside hoardings. Motoring organisations were able to place effective pressure on some of the more prominent advertisers. In 1927, the Vacuum Oil Company declared its opposition to placing advertising that ''would tend to disfigure or mar the natural beauties'' and would in future confine its advertising to the unsightly vicinities of towns. Yet the campaign against other advertisers continued, and the North and South Island motor unions repeatedly lobbied the Government to introduce legislation to ban all roadside advertising.

The campaign attracted a great deal of respectable support, not least from the Governor-General, Lord Bledisloe, who in 1932 secured the oil companies' assurance that they would remove their advertising from country roads.

The campaign prompted at least one case of direct action. Protests against unsightly signs along the Cromwell Gorge line in Central Otago had been made to the Minister of Railways without success by the Otago Motor Club and a range of promotional and environmental associations. Frustrated at what they saw as the Government's lethargic indifference to hoardings in areas of natural beauty, a group of apparently respectable professional men from Dunedin set off inland to ''clean up'' the Kawarau Gorge. The four men were medical practitioners, including well-known 65-year-old Port Chalmers surgeon William Borrie, who was a prominent member of both the Otago Motor Club and the Amenities Committee of the Expansion League.

''Intoxicated with zeal'', as the magistrate put it, Borrie and his colleagues cut down five signs.

Convicted and fined for wilful damage, the four medical men explained their motivation: ''Our scenic routes are strewn with placards, sheds and roofs of buildings are daubed with advertisements, even the trees, fences, and rocks are not immune. The craze for advertising has reached such a pitch that no place is sacred; the greater the natural charm, the more opportunity for vulgar display ... Surely the road users have some rights.''

Despite the widespread support for the campaign against hoardings, its success remained limited. On the eve of World War 2 the national conference of beautifying societies was still plugging away at the Government to do something about roadside advertising. Internal Affairs was favourably disposed, but the Railways Department dug in its heels, as it made almost £3000 a year from its hoardings (or almost $300,000 today).

The editor of The Press ''deplored ... the fact that the activity and influence of the Railway Department have unquestionably prevented reform while they have extended the mischief''.

Mayor of Christchurch Dan Sullivan had expressed his opposition to advertising hoardings, but on becoming Minister of Railways in 1936 he suddenly decided they weren't so bad after all, so he gave the Canterbury Roadside Beautifying Association the bum's rush. The question was not to be resolved until well after World War 2. The president of the Marlborough Automobile Association had summed it all up in 1930 with the universal truth that commercial operators ''mostly are amenable to reason, but you can't get any reason out of the State''.

- Alex Trapeznik is an associate professor in the University of Otago department of history and art history. He has research interests in the burgeoning field of public history and is particularly interested in historical and cultural heritage management issues in New Zealand.