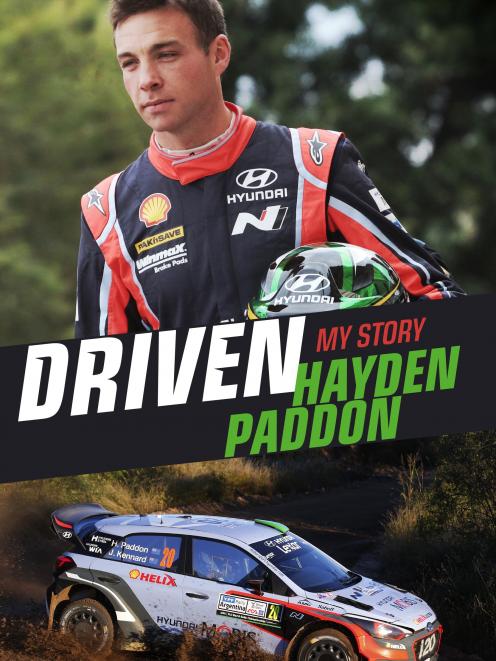

Earlier this year, I was incredibly privileged to ghost-write World Rally Championship (WRC) driver Hayden Paddon's autobiography with him. Having not written a book before, it was a huge challenge but ultimately Driven is the project I am most professionally proud of in my entire career.

I've chosen this extract as it is the "golden" moment of Hayden's career - the culmination of 20 years' striving to climb to the pinnacle of the WRC. It details his all-important relationship with long-time co-driver John Kennard and also shows the level of dedication it takes to become the only New Zealanders to win a WRC round.

When I interviewed Hayden for this section, he revealed an intriguing backstory to the final two days of the 2016 Rally of Argentina that I had not known about. I haven't included it here - you'll have to read Driven to find out which WRC driver he had a blowout with - but, trust me, it's a fascinating one!

I was conscious that the rally win was a huge, lifetime achievement and consequently needed to set the scene, and bring the sounds, sights and even smells to life for the reader. YouTube videos of on-board camera footage from El Condor were vital for me to be able to visualise the bizarre lunar landscape and how its infamous rocks and ruts make a WRC car react. A lengthy phone conversation with John also augmented Hayden's memories of how the suspenseful end to the rally played out in the car.

We initially thought this chapter might make a good lead-in hook to the book, so I'd had a crack at writing it early in the process. It didn't work for the beginning of Driven, but I had received some detailed feedback from the Penguin Random House editors on it. Revisiting the chapter a few months later reinforced how much I'd learned about storytelling, suspense-building and casting back to reoccurring themes since I'd started this project.

The late Scottish rally driver Colin McRae was Hayden's childhood hero and he features throughout Driven. It was fitting to weave him back in on this final stage where Hayden was able to channel exactly that same "kind of semi-spiritual zone where [Colin] was completely present while racing and able to go with the flow, blending man, machine and speed" that his idol had used to claim his sole WRC title victory in the 1995 Rally of GB. - Catherine Pattison

MAKING HISTORY IN ARGENTINA

We had a long touring section on the road out to the first stage, which took John and me up to the top of El Condor. It was one of the two stages to complete that day - El Condor downhill once, then around to the other side of the mountain range to do Mina Clavero. Then we had one last run, downhill again through El Condor.

This was the stage I hadn't wanted to do last year. Now I was grateful that Hyundai management had insisted I got my butt back in the car and completed the final stages. I needed every ounce of prior knowledge of these stages if I wanted to come out on top today.

We always stop the cars one or two kilometres before the start of a stage. It gives us time to warm up the tyres and brakes. Then we wait for our allotted minute to check in at the stage's start line. Seb was in front of us and I knew he'd be trying to play mind games with me.

Before the rally starts, most of us will go for a short run to get the blood flowing. Seb [Sebastien Ogier] started running up towards me. Turning around, I ran in the opposite direction. Again, I was trying to avoid him. I'd dealt with mind games back in my early NZRC days and, today of all days, I didn't want to play them.

If they'd been stages I liked, then no problem. But they weren't. Nervousness threatened to destroy my concentration. El Condor was 16.3km down a tight, winding mountainside - in the worst fog I've ever seen.

Up to 100,000 spectators crowded along the road, some so close I could have reached out the window and touched them. Not that we could pick them out today. For two-thirds of the stage, we could literally see only 5m in front of the car.

John was calling our pace notes based on where he felt we should be on the road, but it was difficult for him because I was stabbing on and off the gas, trying to look for the corners, looking for the line of sight. The car felt incredibly slow.

Usually I thrive in adverse conditions - today, I didn't. There was too much riding on the stage time, and the terrible visibility meant I couldn't fully commit. On-off, on-off the accelerator, the anti-lag popping and banging like fireworks exploding and echoing off the rock walls. I couldn't gauge the corners properly, but kept trying to push myself.

Grow some balls. Channel some Finnish sisu. Anything to get through this stage faster. I worried that we were haemorrhaging time. It wore me down.

Towards the bottom of the hill, I made two mistakes in hairpin corners, stalling the car. By the time we got to the end, I was distraught. All I could think was that I'd thrown the win away already.

We normally go well in the fog compared to everyone else, but this felt like my worst-ever stage. The fog affected our time so much that when we went through El Condor later that same day, we were a full minute faster in clear air.

It turned out we'd only lost 7.4 seconds - much less than I thought.

Maybe we could win this rally? I dared to hope. My confidence began creeping back on board.

Another long road section over to the other side of the mountain followed, before we came up the 22.6km Mina Clavero. Rougher and harder on the car than El Condor, it's equally twisty. The stage is laden with bedrock, which could easily rip out our suspension, and the loose football-sized rocks lying all over the road could puncture a tyre easily.

Going off-line would instantly be punished because the road is only as wide as the car in some places. Rocks, cliffs and boulders line the road.

We started this second stage with just over 20 seconds on Seb. I concentrated on ducking and diving through the lunar landscape. The suspension soaked up the rough terrain as if it were smooth. The regular banging, as the solid rock roads crashed against the car's underbody protection, was muffled by our helmets.

The landscape flashed by like a series of snapshots on fast-forward. There were spectators everywhere, waving, cheering and taking photos. I ignored everything, urging myself to blip through the gears faster, brake later into the corners, gain milliseconds wherever I could.

Once we came to a halt, the team messaged through the stage times. Horrified to see how much slower we were than Seb, my heart sank. We weren't snails - we finished third-fastest on the stage. But, catching us off guard, Seb had just pulled a blinder and took 20 seconds out of us.

For 10 minutes after that penultimate stage, I despaired. Along with probably 99% of the millions of viewers watching Rally Argentina on TV, I accepted that Seb was going to catch me on the final stage.

Then the red mist came down again.

Nah. No way can I let this French guy beat me. John and I have just fought through three days of rallying, through 20 years of my career, to get to this point.

Going into the rally's last stage, I shook myself free of negative thoughts. I've got a chance to win this. My dream is within reach. Grab hold of it with both hands.

There was no pep talk from John on the road stage back to El Condor. We kept to ourselves. When there was pressure, or we were nervous, we didn't talk in the car.

Before the stage, we had a regroup as we sat around for about an hour waiting for the live TV programming to catch up. There's always a long delay before the last stage of every rally to provide a safety blanket for the organisers, in case the rally is running behind schedule. There was a parc ferme about 500m before the stage, so I pulled out my tablet to study the on-board footage of El Condor again. Starting it up, the battery sign flashed 10% left. The display was so dim I couldn't see it. I lay down on the ground, halfway under the rally car, in the shade, to see the screen properly. That's where I stayed for 20 minutes. People around the parc ferme were muttering about how strange it was. They wanted to know what I was doing under there, or if there was something wrong with the car.

Over the previous five years, the level for WRC drivers had gone up and up and up. Everybody pretty much knew the roads, but it was all about trying to find the optimal line through corners and how to link them smoothly. That was what I was doing watching the video. I wasn't watching it to remind myself of the road. I already knew it. I was reminding myself of trigger points, of where I wanted to position the car on the apexes and where I wanted to carry the speed.

We went into that final 16km power stage with a 2.6-second lead. I wondered what my rally hero Colin McRae would've done in this situation. In my head, I could see him smashing stage record after stage record on Rally GB, and beating Carlos Sainz. At the time, the commentators talked about him entering some kind of semi-spiritual zone where he was completely present while racing and able to go with the flow, blending man, machine and speed.

That's what I found heading back down El Condor. When the green light flashed go on the start line, I drove the stage of my life. It was surreal. At the time, it felt like I was not there behind the wheel. It was the easiest it has ever been to drive the car, but I was on the knife-edge limit.

There was a corner where I slid slightly too deep into a hairpin. "Grrr," I growled to myself. I was so in the zone that when I made this one tiny mistake out of hundreds of corners, I was kicking myself. Giving it everything, I was only driving for one thing, the one thing I really wanted.

This is one of the roughest stages of the championship - I didn't feel a single bump. El Condor felt smooth. Everything flowed from start to finish. It was one of the most incredible experiences I've ever had in a rally car and I've been trying to replicate it ever since. The switch for finding the zone had been flicked. So easy. So natural. For that 16km, everything else in the world disappeared.

The ticking sound from a hard-working engine that had completed its duty filled the cockpit. Heated high-performance fuel and oils intermingled to form the distinctive smell of a hot rally car at the end of a stage.

I knew Seb had clocked 12 minutes and 59 seconds on El Condor in 2015.

"We did a 13.08," John said.

"We couldn't have done any more. We gave it a good go," he said, compassion in his eyes.

We didn't have radio contact with our Hyundai Motorsport team. That was the one year they decided not to have radios in the car. Normally, after we crossed the finish line, the co-driver would radio in that we'd cleared the stage and the team would tell us the other drivers' times. No radio meant we had no idea of Seb's time.

The time board at the stop control would tell us.

In the short distance between the finish line and the stop control, I'd already admitted defeat. I spent that 20 seconds trying to compose myself to talk to the waiting media. Everyone watching the rally online or on TV would already know the result. We were in the dark.

The official put the time board on the car's bonnet and we scanned down the list of drivers. The window wiper obscured Seb's time.

"Lift it up! Lift it up!" John yelled, motioning with his hands.

Finally, the bottom of the board was visible.

"Nah, John, you told me the wrong time," I reacted with utter disbelief.

Looking at him, I asked the question.

John was frantically adding up times.

I looked out at the media surrounding the car. They all had poker faces. Give me a clue here, have we won or not? Their cameras were poised but none of them were cheering.

Thumbs up, thumbs down, I signalled, asking for an indication.

"Yes!" one of them yelled.

I clapped John on the knee.

"We've won," I whooped, leaping out of the car and straight up on to the roof - punching my fists in the air.

John was still in the car. Professional to the end, he was double-checking the times to make sure we truly had won. At 57 years old, he had just become the oldest co-driver to win a WRC round. We had won our first WRC rally.