A paper road separates Kew from Corstorphine.

To the northwest, Lockerbie St, on the hills bounding South Dunedin’s southern flank, is solid, tangible. It is a street name manifest in rough gravel chip and hard-wearing bitumen.

On the other side of its intersection with Middleton Rd, however, Lockerbie’s southeast extension is not much more than a line on a map; a pot-holed, loose gravel track that disappears into scrubby bush.

But it would be wrong to think this paper road is meaningless, that it is without significance or power. It is the dividing line between two suburbs; more than that, two worlds.

On the uphill side, starting at 101 Middleton Rd, is the mostly low socio-economic suburb of Corstorphine. Portions of this neighbourhood, including the eastern side of Middleton Rd, have been ranked in past censuses as 10 out of 10 for their high rates of deprivation.

Three meters away, beginning at 95 Middleton Rd and extending downhill on the eastern side of Middleton Rd, is an upper-middle class slice of the Kew suburb, rated in those same censuses as a three for its low rates of socioeconomic hardship.

Angus Mackay lives at 95 Middleton Rd. He lives there with his dog, ZB.

As soon as he saw the Kew property for sale online, with photographs of million dollar coastal views, he knew its potential. He has since renovated the kitchen, added a conservatory and developed the garden.

"It’s a great spot. I was lucky to get it," he says.

Angus is friendly with the neighbours one house up the hill. But their lives bear little similarity.

Neil Ross and Tania Young moved into the Housing New Zealand rental, at 101 Middleton Rd, in April. They share the 1945, four bedroom, wood and tile, state house with their five children (plus a sixth every other week) and a dog.

Neil and Tania have lived in various Dunedin rentals. They were pleased to move from the previous house of four years, in Calton Hill, where their children, aged 5 to 19, were often unwell. As soon as they saw the Corstorphine house, with its great views and extra space, they wanted to move in.

Not that that makes much difference to Neil, Tania and their family.

"I would love to buy this place," Neil says looking over his shoulder at the weatherboard rectangle they call home.

"But while the kids are young and money is scarce, it’s just about survival."

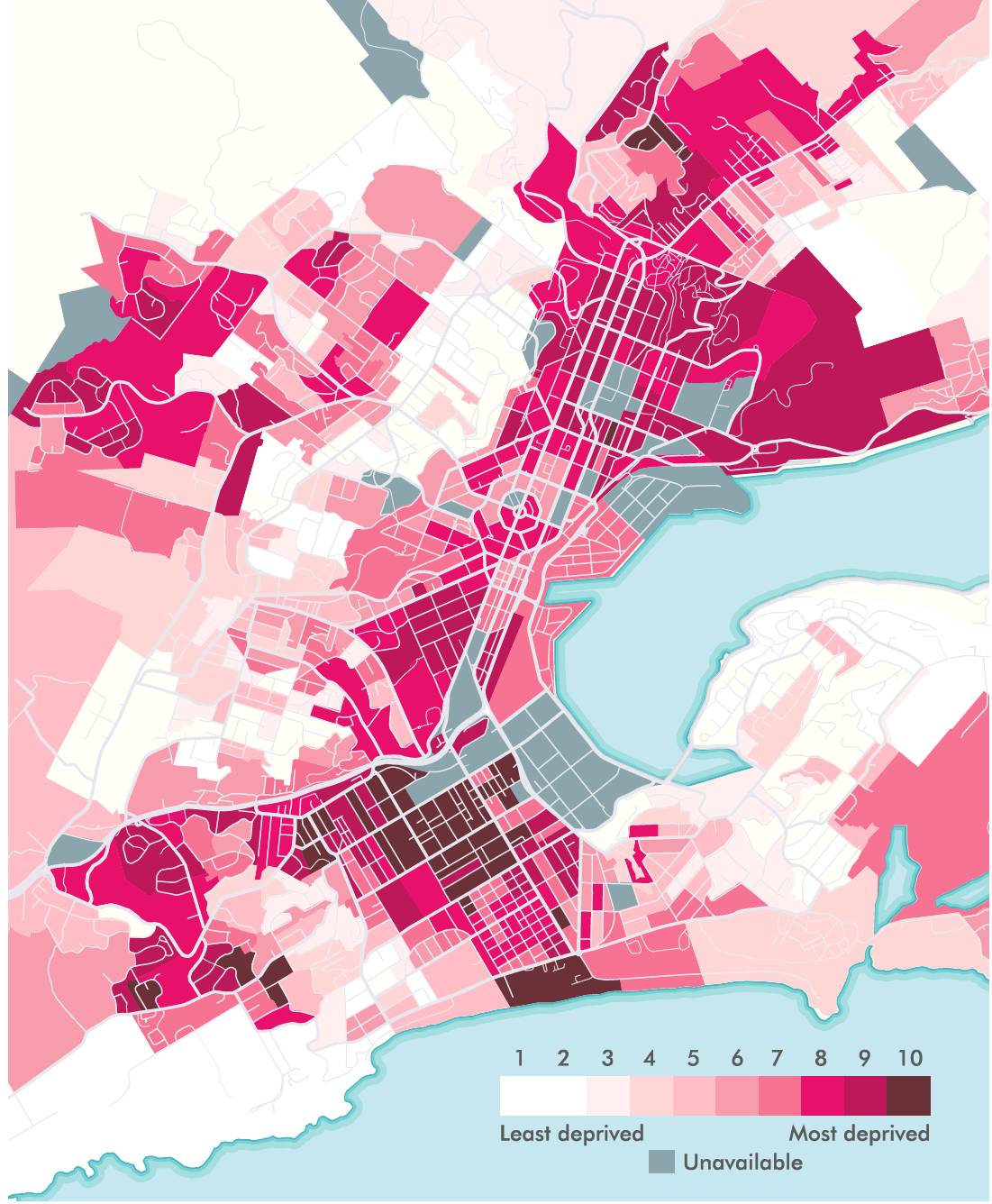

The New Zealand Index of Socioeconomic Deprivation (NZDep) is updated every five years. Using the latest census data, NZDep divides the country into just under 30,000 distinct chunks based on socioeconomic information such as employment, housing, education, income and access to the internet. Each geographic chunk is given a decile rating based on its relative level of socioeconomic deprivation; 1 for the lowest levels of deprivation and 10 for the highest.

In essence, it is a map detailing the distribution of poverty throughout New Zealand and any changes to that distribution over time, lead author Prof Peter Crampton says.

The next Index, NZDep2019, was delayed by problems with Census 2018 but is due out within days.

"In the end we got a very satisfactory outcome, with some imputed data. I’m confident about the accuracy of the picture it presents," Prof Crampton, who is professor of public health, at the University of Otago, says.

The picture that emerges from this, the sixth NZDep, is not encouraging.

"It shows what it has always shown, that there is considerable advantage and considerable disadvantage within New Zealand," he says.

"The level of disparity in New Zealand has become deeply entrenched since the first NZDep, in 1991.

"What it shows, to me, is how little we now care about inequality."

History and statistics confirm this.

Dr Brian Easton (76), who is a mix of economist and historian, has said, "Once upon a time New Zealand identified itself as egalitarian. Phrases like ‘a classless society’, ‘Jack’s as good as his master’; ‘a working man’s democracy’ were bandied around, often without much critical thought".

For the first half of last century, red- and then blue-hued governments introduced policies and Bills that increased the social welfare safety net and lifted the living standards of most New Zealanders. Universal superannuation, welfare payments for the poor and unemployed, largely-free health care, state-assisted home ownership, no-fault accident compensation, Government-guaranteed full employment ... New Zealand was vaunted as a showcase of social democracy in action.

There were gaps. Women and Maori were among the most glaring examples.

"Perhaps the most charitable interpretation," Dr Easton has written, "was that ‘New Zealand as an egalitarian society’ was an aspiration, how New Zealanders wanted their society to be."

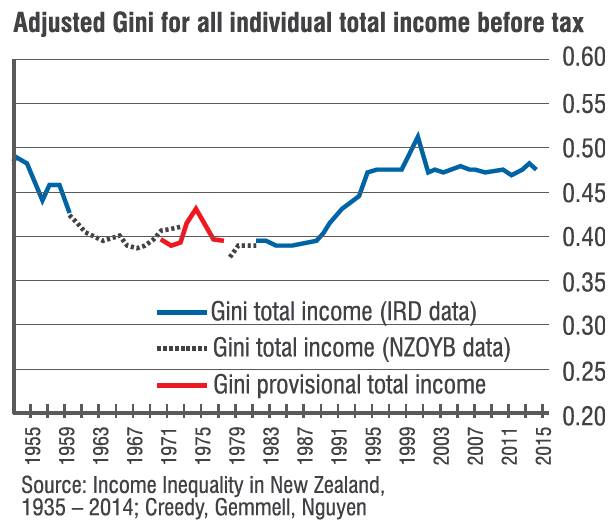

The overall picture, however, was of a society where living standards were rising and the gap between rich and poor was narrowing. New Zealand’s Gini coefficient — a measure of inequality — decreased dramatically during the 1950s and then, with a few hiccups, gently declined for the next two decades.

But all that changed in 1984.

Once again, a red government and then a blue one transformed the economic and social landscape.

Within days of the 1984 Labour election win, a grouping of the country's leading business sectors had written to incoming prime minister David Lange with their vision for a new economic model.

Their prescription included a focus on reducing inflation and keeping it low, greater labour market flexibility, increasing competition throughout the economy, removing regulation that was not business-friendly and big cuts to company tax and to income tax paid by high earners. The revenue the Government lost through its tax cuts was to be made up by reducing government spending, including on welfare, and introducing more indirect taxation.

New Zealand underwent reform on an unprecedented scale.

What Labour did not implement, National completed in 1991 with the Employment Contracts Act and the Mother of All Budgets.

The country became a neoliberal market economy poster boy. Individual wealth creation took precedence over equality. By virtually every measure, the gap between rich and poor has increased.

New Zealand’s Gini coefficient soared in the decade to the new millennium, then dropped slightly, and has since spluttered along at a level of inequality not seen since the mid-1950s.

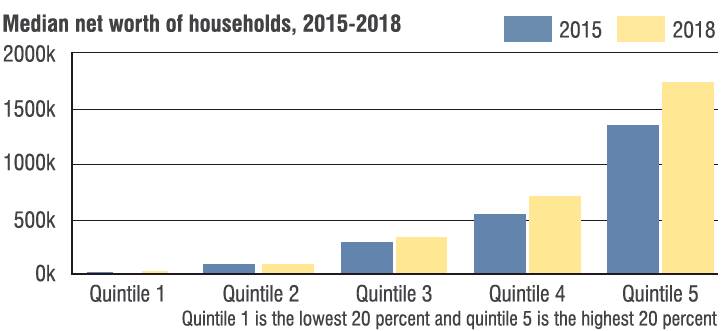

During the quarter-century to 2010, the capital income of the most wealthy quarter of New Zealand households grew by 9.4% while the capital income of the poorest quarter decreased by 3.9%.

Today, the country's two wealthiest people, Graeme Hart and Singapore-based Richard Chandler, own the same amount as the poorest 30% of New Zealanders. The richest 1% of Kiwis own 20% of the wealth, while 90% of the population owns less than half of the nation's wealth.

The disposable income of high-income households is now 278% larger than the disposable income of low-income households.

In the 2013 census, more than 23% of Maori lived in NZDep decile 10 areas, compared with about 4% of New Zealand Europeans. Prof Crampton is not expecting this picture to change much when the latest statistics are released.

The 2019 Child Poverty Monitor report, released last week, revealed 174,000 New Zealand children live in households that cannot always afford enough healthy food.

"During my working life, we have massively widened the income distribution and entrenched wealth at the upper end in a way that it had not been entrenched before," Prof Crampton says.

"That social expectation has radically altered, whereby we expect to contribute less and to have relatively higher disposable incomes.

"We’ve been sold that as the desirable goal.

"And the selling of this consumerist vision has, by and large, been quite deliberate.

"But it has become normal. It is now the air that we breathe."

The world it produces is a splintered mirror; radically different views of the world and experiences of it, jammed tightly up against each other.

Angus, of Kew, was raised by Kiwi parents in the Scottish university town of St Andrews. During university studies, he played rugby for the Scottish under-21 team, touring South America and Australia. After university he joined the British army and served as a troop commander. He also worked in marketing for IBM and travelled in Europe and the United States before switching to teaching.

At the age of 35, Angus got a serious case of glandular fever. Ever since, he has suffered significant and at times debilitating chronic fatigue.

Despite, and in between bouts of, the myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) he has completed a master’s degree in education, emigrated to New Zealand, taught at high schools and got most of the way through a PhD. At present, as he is able, he volunteers at Red Cross and does relief teaching. With two properties and ME/CFS, Angus is asset-rich but income-poor. Rental from the Auckland house helps him get by.

Neil and Tania, of Corstorphine, have travelled, although not outside New Zealand. Tania was raised in Dunedin. Before she became a full-time mum, she spent several months touring the North Island with a travelling carnival. Neil grew up in West Oamaru. He has been a factory worker for a Dunedin petfood manufacturer for five years and once attended a work conference in Napier.

Tania needs a large amount of dental work. But when the budget barely stretches to rent, heating and groceries, functional teeth are an unaffordable luxury.

"I’m all for healthy food alternatives for the kids," Neil says.

"But when mandarins for one day’s school lunches cost the same amount as a week’s worth of packets of chips; cost-wise it’s out of the budget."

Neil has heard families with two children and two incomes talking about "doing it tough".

"They don’t really know. Try doing it with five kids and one income."

The evidence is that everyone is better off when inequality is reduced. Research shows that societies with greater equality have less crime, higher levels of happiness (including among the most well-heeled) and stronger social cohesion.

In 2016, at the World Economic Forum, a gathering of the world's ultra-rich, in Davos, Switzerland, a panel of experts told the audience that inequality was one of the key threats facing the global economy.

There are plenty of ideas about how the gap between rich and poor could be reduced. Most centre around re-jigging tax rates, introducing new taxes or bringing back old ones.

That is because the major driver of socioeconomic inequality in New Zealand has been changes to the taxation regime, Assoc Prof Brian Roper says.

The head of the University of Otago politics department advocates a more progressive taxation regime, i.e., paying more tax the more you earn; reducing GST and removing it from household necessities such as fresh food and electricity; and taxes on land, capital gains and financial transactions.

"That would lead to a very substantial reduction in inequality in New Zealand," Prof Roper says.

Tax is not a polite word in most wealthy circles. The argument is that the top 10% of income earners already pay 43% of the net tax. But at the same time, 2015 figures from Inland Revenue revealed that more than a third of the New Zealanders worth more than $50 million declared annual income of less than $70,000.

In which case, death taxes could be useful in the redistributive toolbox.

New Zealand got rid of death taxes in 1992, when then-Minister of Finance Ruth Richardson described them as a "misguided notion that people should not be permitted to accumulate too much wealth".

The bottom line, Prof Crampton says, is that if governments really wanted to effect change, they could.

"We need to once again alter the distribution of wealth in order to narrow the gap between rich and poor.

"It is the cumulative effect of social and economic policies over time that will alter these distributions."

National and Labour both say they want to reduce inequality.

Carmel Sepuloni, Minister for Social Development, makes the bold claim that this Labour government has done more than any government in the past three decades to set policy and make changes that will address inequality.

She points to the $5.5 billion Families Package and Budget 2019 changes which she says will lift up to 74,000 children out of poverty by the middle of 2021. Sepuloni also mentions last week’s announcement of $12 billion for infrastructure projects.

She admits there is more to do but says the Government is working to realise its vision for a welfare system that "ensures people have an adequate income and standard of living, are treated with respect and can live in dignity and are able to participate meaningfully in their communities".

Labour turned down the opportunity to introduce a capital gains tax to fund the work. Borrowing will likely be important.

National’s social development spokeswoman is Louise Upston.

Upston believes New Zealand should be a place of "equality of opportunity"and sees employment as key to that.

There should be a strong safety net to help people get through tough times and back on their feet, but "National believes the best route out of poverty is through work," Upston says.

"We want to remove barriers to work so that more New Zealanders benefit from the choices and opportunities being in work gives."

History suggests, "remove barriers" means strengthening employer rights. References to progressive tax are conspicuous by their absence.

The NZDep is a tool to help governments see where they need to allocate additional resources to address socioeconomic deprivation.

But Prof Crampton fears substantial change will not happen easily.

"The elites maintain their own privileged status. Neoliberalism will not give up without a massive fight.

"The concentration of wealth now means we probably need catastrophic challenges to that, such as the Great Depression, or a war, or a revolution, or whatever, to change a system with that much entrenched power."

The last time New Zealanders embraced a largely egalitarian vision was on the back of a world war that lasted six years, killed 12,000 New Zealanders and wounded a further 19,000.

The effects of the social cohesion it produced, in ethos and in government policy, lasted decades.

In 1972, a Royal Commission of Inquiry on Social Security was established by a National government. The commission’s forthright description of the sort of society it believed New Zealanders wanted is astounding by today’s standards.

"No-one is to be so poor that he cannot eat the sort of food that New Zealanders usually eat, wear the same sort of clothes, take a moderate part in those activities which the ordinary New Zealander takes part in as a matter of course," the commission stated.

"The goal is to enable any citizen to meet and mix with other New Zealanders as one of them, as a full member of the community — in brief, to belong."

Angus is surprised those words came from a commission established by a National government. But he heartily endorses the sentiment. He is dismayed by the "terrible disparity between the haves and the have-nots". He says the minimum wage should be set at the level of the living wage. He is angry at the previous National government for "allowing hospitals to crumble, not putting money into education and doing nothing to address poverty". He is disappointed Labour did not introduce a capital gains tax and use the extra revenue to reduce inequality.

"Even as a property owner, I can see the capital I have gained hasn’t been worked for."

Neil and Tania are equally surprised when shown the quote encapsulating the commission’s egalitarian vision.

"That’s definitely the sort of New Zealand we should have, and it’s not the sort of country we do have," Neil says.

A New Zealand he has never seen or experienced blooms in his mind’s eye. It is a vision he does not want to lose.

He pulls out his phone.

"Can I take a photo of that?"

Comments

"The concentration of wealth now means we probably need catastrophic challenges to that, such as the Great Depression, or a war, or a revolution, or whatever, to change a system with that much entrenched power."

Wow. What scary thinking.

I’d prefer to initiate change by challenging entrenched thinking by removing the privilege of the elites in our state run education system commonly known as tenure.

Without a means of challenging these entrenched incumbents, our university educated political class simply regurgitate the same limited post-modernist (Marxist) view of the world.

When it comes to the divisions now evident in our society, I’d say the driving forces are the push for so called diversity and the rise of identity politics.

Christian identarianism, White identarianism. Quite.

The entrenched Right spin the idea that inequality is normal, the right thing.

Stratified class distinctions are not the Dunedin way. Maori Hill may never go to The Flat, but they don't crow about it.

Inequality is normal. It exists throughout the natural world from plants to animals between and within species. That is how evolution works.

Empathy, cooperation and collective security is a survival strategy utilised by human communities and the binding agent is trust.

The Christian narrative that followed the Reformation facilitated lifing the West out of perpetual poverty and that prosperity has spread around the world.

This same narrative speaks of supporting the poor, forgiveness, sharing, faith, respect, truth and being your most productive self. I find no fault in that.

It also warns of envy, jealousy, bitterness, tribalism, conceit, false beliefs and lying. I find no fault in that neither.

It’s as much a statement about the human condition as anything else.

Marxism and postmodernism promotes nothing more than equality by totalitarianism dictated by an elite that considers their moral view is above all others. That’s why it’s never worked, leads to mass death and always will. I’m against that.

You’ve got a lot to learn if you think you speak for the ‘Dunedin way’.

Very sad. Something does have to change, especially as the gap between the have and have not's is continually getting bigger. We used to have a 40 hour famine for starving kids in Africa and other 3rd world places, now NZ needs charities to feed some of our poorest.

Whats the answer, God knows, but getting our richest citizens to pay a fair amount of tax is a start and at the other end of the scale making the first $30K of income tax free would sure help reduce the number of struggling families in NZ.

The ODT seems to be taking a definite lurch to the left under the current editorship, and this article is a good illustration of that. Long on emotive rhetoric based on little more than anecdote and short on solid statistically verifiable research. It’s the latest in a disappointing trend from what was once a paper of solid journalism.

Or is more that the ODT is reporting on the fact that things out there really are getting tough? Goodness knows, this so called 'rhetoric' you speak of has been well studied and researched for nearly a decade now. The findings are that we have poverty in NZ now that we haven't seen since the Depression. For a modern, wealthy (for some), so called civilised society, I don't see that we are doing very well at all. When the fact is presented, that a third of our children are brought up in poverty, what does that tell you? Or are you more concerned with 'solid journalism' that suits your belief? Does it tell you that ODT current editorship is 'left leaning', or does it tell you that something is very wrong with our modern financial system? Big words, denials, and dismissive statements aren't going to fix the problems that are growing by the day.

That Deprivation Index map needs some serious re-work: it's missing a non-residential category (ie no houses). For example the start of the Green Belt around the Northern Cemetery and sports fields are ranked high on the deprivation index, but there is no housing in that area. Granted, the residents of the cemetery aren't living the high life but that's probably not the intent of the map.