Christchurch writer Jonathan Allan looks into the life of William Rigney, the man who provided the pine plaque for the unknown soul found drowned in the Clutha and was buried at Horseshoe Bend in 1865.

Poor Mr Rigney must turn in his grave at Horseshoe Bend on the Clutha River downstream from Millers Flat, when he reflects on the wording on his tombstone Here lies the body of William Rigney. The man who buried ''somebody's darling''.

This is a reference to the grave beside Rigney's, the tombstone of which states: ''Somebody's Darling Lies Buried Here.''

On his own admission Rigney did not bury ''Somebody's Darling'' - in a letter to the Tuapeka Times on January 19, 1901, and in which he coined the phrase ''lonely grave''.

But what of Rigney himself? Much has been written over the years about Rigney and his association with the ''lonely graves'', but what sort of a person was he? Without all the fine detail, I will try to paint a picture of this interesting character of the Otago goldfields.

On his death in 1912, Rigney's obituary was able to tell little of his early life.

The unidentified writer admitted that ''Of Mr Rigney's early life and history little is known to us. He was of Irish descent, was well connected, claiming kinship with a Bishop of Sydney; he received a good education and was altogether well informed.

''As a young man he followed a sea-faring life ...'' (Tuapeka Times, June 12, 1912, and Mt Benger Mail, June 19, 1912). Picking up on some of these points, Rigney's death certificate gives his age as 79, meaning that he must have been born in or near the year 1833.

His place of birth is stated as Loughrea, Galway, Ireland. As to claiming kinship with a Bishop of Sydney, there was a Right Reverend Monsignor (Dr John) Rigney of New South Wales.

In 1887, Dean Rigney, who was at the time the Archdeacon of Sydney, was made a Prelate of the Pope's Household with which came the title of Monsignor.

With such a title and position it may not have been too much of a stretch for William Rigney to simply describe him as a bishop. Monsignor Rigney died in 1903. From the obituaries written about him we learn that he was born in Ballinasloe which is about 30km from Loughrea, so possibly this person was William Rigney's kin.

As to the reference to Rigney having followed a seafaring life, we are none the wiser, unless his voyage to the antipodes could thus be described!

The only person to have known Rigney and to have written about him was Robert Thomson Stewart.

An obituary for Stewart (Otago Daily Times, December 5, 1944), who died in his 78th year, described him as having been born at Island Block and ''followed his father in the quest for gold when the famous gold rushes were at their height''. Stewart was ''well known in engineering and mining circles'', and also known for a keen interest in the early history of the province.

''After retiring from his active mining associations, Stewart closely identified himself with the Otago Early Settlers Association to which body his knowledge of life in the early goldfields was invaluable.''

In 1942, Stewart gave a talk on Dunedin radio station 4YA about Hugh Craig, the Otago coach driver. Somewhere around this time he gave another talk entitled ''The Nameless Grave at Horse-shoe Bend''. The manuscripts for both talks are typewritten with amendments by hand, and are held in the Hocken Library.

Putting aside, on this occasion, Stewart's account of the lonely grave, let's look at what Stewart had to say about the Rigney he knew. The first reference is this: ''In a theological college in Dublin in the year 1858, a student named William Rigney disagreed with his superiors and was expelled. He then joined a group of young men who emigrated to Australia where he spent some years as a private tutor, and when the rush to Gabriels Gully in Otago took place in 1861, came to New Zealand to try his luck on the goldfields.''

We have to accept Stewart's account of Rigney's life in Ireland, as there is no confirming evidence available at present. We do know, however, that Rigney travelled from Melbourne to Port Chalmers on the ship Atrevida, arriving on October 12, 1861 (Passenger Lists Victoria Australia Outwards to NZ Ports), and that he was at Gabriels Gully in 1861.

In the Gabriels Gully Jubilee booklet, published in 1911, is the entry: ''Rigney, Wm., Island Block'' among those who notified the Jubilee Committee that they were there in 1861.

To end Stewart's talk he gives some more detail, eloquently put, from his personal knowledge of Rigney: ''He was possessed of literary tastes, and always in his camp one would find a book or two not usually seen except in a library.

''His handwriting was the best I have seen, and he was often called upon to draft letters for publication, upon subjects of public interest, or to engross a petition for presentation to a public body, or to some visiting dignitary.

''He was ready at all times to take up the cudgels on behalf of any worthy cause which lacked assistance.

''His mother, of whom he always spoke with reverence and affection, had hoped to make him a Priest of the Roman Catholic Church, an office of which I am sure he could, and would have filled with honour, but his imperious nature could brook no restraint and his refusal on several occasions to submit to discipline resulted in his being expelled from College.

''With a long farewell to his native land, and all who held him dear, he joined an emigrant ship for the Colonies, and later when travelling the Golden Road in search of fortune, Destiny turned his steps to diggings at Horse-shoe Bend where his mortal remains lie buried, and his name is enshrined in a slab of marble, in the shadow of a nameless grave.''

While there is a good deal in Stewart's account of the lonely grave itself that is clearly fanciful, (and which I am not going to debate here) at least the words about the background and personality of Rigney himself I believe we can fairly accept as an accurate recollection.

There seems to be little doubt that Rigney would have stood out from the typical gold-miner of the day as being an educated and cultured person, and valued as such by the community.

In its issue of June 5, 1912, the Mt Benger Mail reported that Rigney had recently been found in a state of collapse and was taken to Tuapeka Hospital in Lawrence.

The article concluded by stating that ''He had expressed a strong wish that, should he die, his body would be brought back and buried beside the grave of ''Somebody's Darling'', he having put the original wooden inscription on this grave.

This reference to Rigney's wishes dates back to a letter that he wrote to a newspaper (Tuapeka Times, January 19, 1901) in which he said: ''I have always felt a special interest in that grave, [''Somebody's Darling''] as I have a foreboding that in the end my lot will be the same - viz., a lonely grave on a bleak hillside.''

Rigney died on June 4, 1912, and his wish was fulfilled thanks to the generosity of residents of the district who subscribed the money required for the burial (Mt Benger Mail, June 12, 1912.)

There is no record of Rigney having left a will, and given that the local residents had to contribute to the cost of his burial indicates that after a lifetime of hard labour on the Otago goldfields, Rigney had no financial rewards to show for it.

In looking at the sort of man Rigney was, three different aspects stand out. First and most obviously is his life as a gold-miner, then there is the role he played as a member of the Teviot Valley community, and thirdly is his obvious enjoyment in a good legal argument in which he partook on many an occasion.

Life as a miner

Rigney's first gold mining experience - at least in New Zealand - was in 1861, at Gabriels Gully, and then according to Stewart to the gold fields at Glenore (or the Woolshed as it was known at the time) before heading further inland to the Roxburgh area.

From there he claimed to have moved to Horseshoe Bend in 1865, and remained in the area for the remainder of his life.

Over the years Rigney clearly built up a wealth of gold mining experience, including battling the unforgiving Clutha River, and which was recognised by his fellow miners.

This included constructing water races, dams, sluicing and dredging, and fluming water from one side of the Clutha to the other.

He invented a current motor for pumping water from the river, a device that he patented.

Financially, his mining career appears to have been of mixed success, and he probably reinvested what capital he earned in new mining ventures, but ultimately died penniless.

Life in the community

From the picture Stewart paints of Rigney's character it is not surprising that we find numerous examples from contemporary newspapers of his willingness to play a full part in the community life of the small mining town of Horseshoe Bend and its surrounds.

He was someone never to hold back on issues he regarded as important, and willing to put pen to paper to the Tuapeka County Council and to editors of newspapers, and also to anyone with whom he had an issue to raise.

Some of the particular causes in which he took part, often in the lead and not directly related to mining, were the move to have a cemetery established in the village, the location of the post office, and the establishment of the Loyal Roxburgh Lodge friendly society.

On one occasion Rigney presented a petition to a departing Goldfields Warden - a petition that Rigney probably wrote himself - and although not known to have married or had children of his own, took an interest in the running of both the Beaumont and Rae's Junction Schools.

When investigations were under way for some means of crossing the river at Horseshoe Bend, Rigney was consulted on the matter, and continued to take an interest in the venture of first installing a chair and later a bridge.

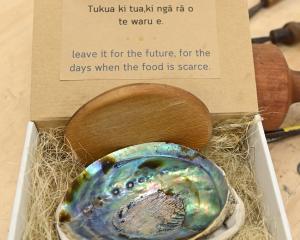

Stewart's reference to Rigney's literary tastes can be borne out by his use of the phrase ''Somebody's Darling Lies Buried Here'' which he carved on the wooden headboard he had prepared for the ''lonely grave''.

This is probably a paraphrase from the poem written by Marie La Coste and published in the United States in 1864: ''Carve on the wooden slab at his head, Somebody's darling slumbers here.''

If any miner at Horseshoe Bend was aware of the poem, Rigney was a very likely choice.

Life as a litigant

Rigney clearly liked a good argument and was not afraid to stand up for what he believed was his right.

As a consequence he was often before the courts as a plaintiff but also, not surprisingly, occasionally as a defendant.

Probably what he thought was his tour de force was his petition to the Provincial Council when he felt he had been badly treated by the Resident Magistrate at Roxburgh.

It was two and a-half pages of argument in a particularly fine hand, confirming what Stewart described as ''the best [handwriting] I have seen''.

There would have been many examples of Rigney's handwriting around during his lifetime - letters written for less literate fellow miners, letters to editors, and officials of one sort or another.

The most extensive account of Horseshoe Bend, Rigney and the ''lonely graves'' was written by J.J. Robertson in 1991, and entitled One Man's Goldfield - The story of William Rigney and the Horseshoe Bend Diggings.

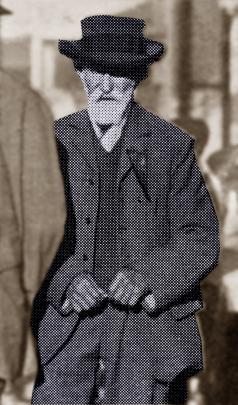

Robertson states that ''No photograph of Rigney has been found ...'', and from my researches, I concur.

We do, however, have two separate descriptions of Rigney.

Stewart, who knew him '' from my earliest boyhood days'', described Rigney as ''slight in build, with fine features, dark hair and eyes, and wore a short black beard.''

In Rigney's obituary, more contemporary comments were made: ''For some years past he was in failing health. Twelve months ago he attended the Jubilee celebrations in Lawrence but it was remarked by many that he was the frailest and weakest man among the sturdy set of old miners present.''

In its coverage of the Gabriels Gully Jubilee, the Otago Witness published in its issue of May 31, 1911, a page of photographs taken around Lawrence during the celebrations, and copies of these are now held by the Hocken Library.

Among these are two street scenes: one captioned ''A snapshot in Ross Place, Lawrence. A few of the old miners line up for a photo'', and the second ''Another street scene - a typical party, who have been discussing incidents of the early days of the rush.''

In 1861 Rigney would have been aged about 28, which was probably a few years older than most of the miners who were at Gabriels Gully.

In both of these photos is the same distinctive individual looking older and more frail than the ''sturdy old miners'' in his company. Given the nature of the man as I have already outlined, and the fact that he remained in Otago in pursuit of gold for the rest of his life, he would have been well known to many of the three hundred odd attending the Gabriels Gully Jubilee and no doubt would have socialised with them during the celebrations.

Therefore we could hope that he might feature in one of the informal photographs taken - perhaps even two! In my opinion the small, elderly, frail man in these two photos could easily fit the descriptions we have of Rigney.

It would be nice to think that we have now discovered a photo of William Rigney, but, of course, we are likely never to know for sure.

-By Jonathan Allan