Eating in the future is going to be about a diverse, plant-based and nutrient-rich diet. So how do we get there? Maureen Howard talks to those with a plan.

When the Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 struck, resident Michael Reynolds learned that the supermarkets only carried enough food to supply the city for three days.

"We were fortunate that there was a lot of food that was donated from around New Zealand and from around the Canterbury region to Christchurch after the earthquakes.''

At the time, Reynolds was living in the centre of the city, inside what turned out to be the army-cordoned zone, "Which gave me a bit of a unique experience, in that we got to wander around and see the central city's brokenness''.

"One of the things that really came to me was that I didn't react in a really negative way, it just kind of opened the city up to a whole bunch of opportunities in my eyes.''

Where others saw rubble, Reynolds also saw potential, and so he started a community engagement project called A Brave New City to find out what values and principles people wanted to guide their changed city.

"One of the points on which a lot of people agreed was that they wanted more green spaces in the city and they wanted places to grow food.

"People started realising, `Hey! I don't know how to grow my food, and it takes time', and concerns like that.''

Reynolds began to look at the land with fresh eyes for its food production opportunities and as a way to "activate communities so that they grow food for themselves, whether it be together or on their own personal bits of land that they have access to''.

In 2015, Reynolds moved to a house across the road from 2.6ha Radley Park and decided to start a community orchard there called Roimata Food Commons. Now in the early stages of becoming a food forest and community garden, alongside native regeneration, "it's taking a very ecosystem approach to everything''.

Roimata joins at least 10 new community gardens and orchards that have sprung up since the Christchurch earthquakes.

"There are new ones in the pipeline all the time and I guess it is a response to that realisation that we don't have security in our food system, as well as bringing people together.''

Relocalising Canterbury's food supply is also a personal journey for Reynolds, as part of which he has stopped eating bananas and pineapples.

"That list will probably grow as I become more and more focused on what Canterbury can grow.''

Christchurch's southerly city neighbour felt the emotional fallout of the quakes. The year following the second major earthquake, Dunedin resident Bart Acres and others organised the first food forum for the city.

With funding from the Dunedin City Council, two more forums followed on its heels, these organised by Andy Barratt, a small organic market garden grower, and a group that included councillor Jinty MacTavish. Out of these gatherings, the community group Our Food Network (OFN) was formally created in 2013 to connect growers, distributors and consumers and to promote the relocalisation of the region's food system.

"One of the things that we need to know is how to make the best of our gardens,'' Barratt says. "We need to be skilful about this, we need to be observant gardeners, we need to be aware that the seasons are changing and that we can grow more things in Dunedin than people thought possible.''

Keen to support people growing food themselves, OFN is now supporting Acres to re-establish a seed-savers network in Dunedin.

"We're seeing that as part of a larger support for home gardeners generally,'' Barratt says.

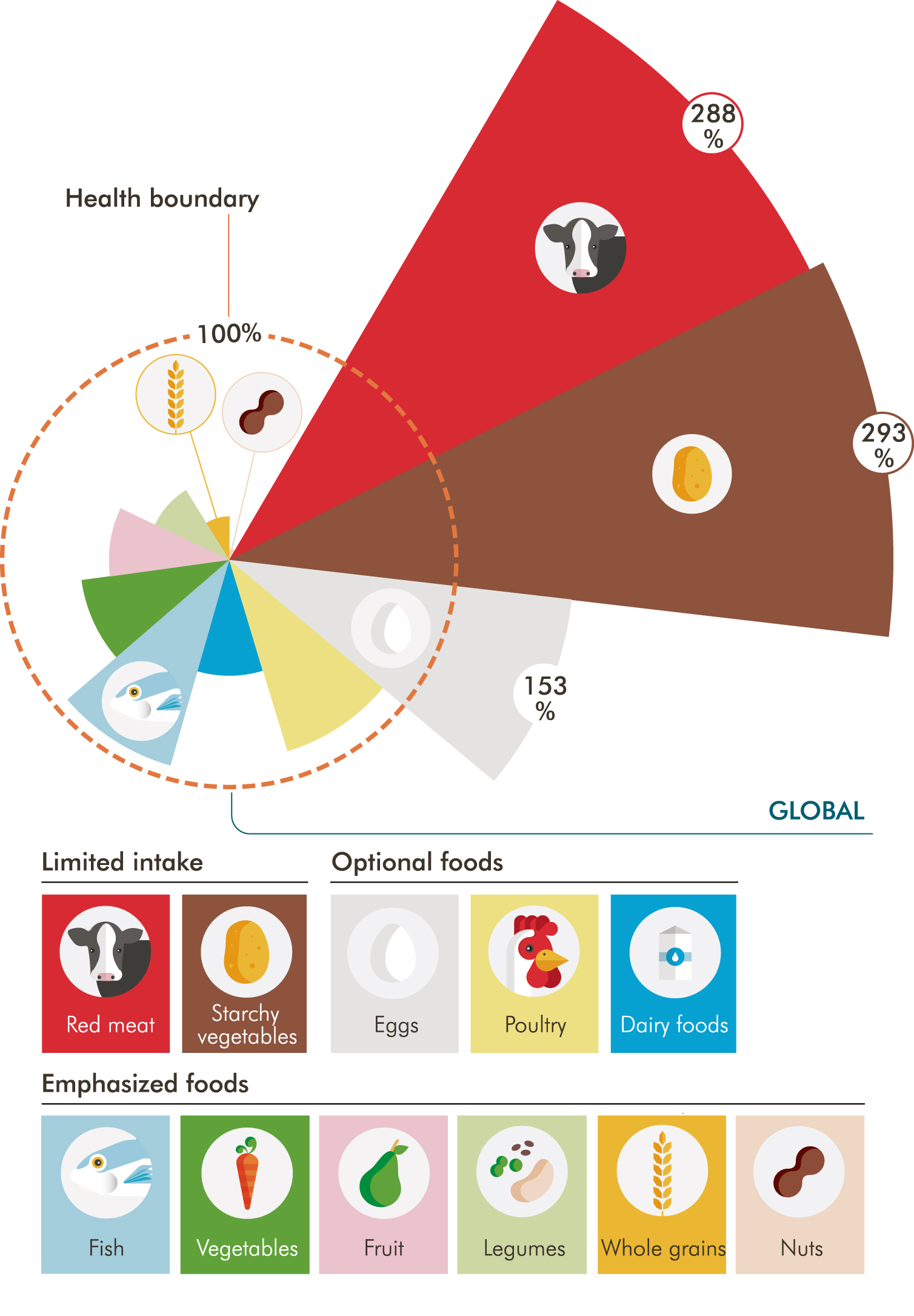

Barratt cautions against looking for a silver bullet to achieve the three key goals for a healthy planet and healthy diet emerging from a growing number of studies; diverse food, nutrient-rich food, and plant-based food.

"There's no one single thing, but lots of things together start to make sense.''

He points out that committing to a relocalised diet could lead to a less diverse one.

"Relocalisation is very much about eating what's seasonal to where you live'' Barratt says.

At the same time diversity within food groups could increase.

"Some of your local growers grow cooking apples which you simply can't get in the supermarket.''

SCALE matters. A global study of farms, published in The Lancet in 2017, found agricultural output and nutrient density in food diminished as farm size increased, but that agricultural diversity was associated with more nutrients, irrespective of farm size.

Backyard gardening represents the smallest scale of production as well as the most local.

"My view is, the best local food is the food you grow in your own garden because you know how it's been grown, and also you can eat it as fresh as possible,'' Barratt says. "The old adage with corn is that you put the pot of water on to boil before you pick the corn!''

In fact, living nearly 40km north of Dunedin, Barratt eats his own corn very fresh.

"You need a warmer summer, but generally speaking we've done all right in recent years to grow corn provided you've got a nice sunny spot.''

Two years after the formation of Our Food Network, the Dunedin City Council established Good Food Dunedin. The DCC's Good Food Dunedin co-ordinator, Ruth Zeinert, says food has an "absolutely'' important role to play in the council delivering for the community.

"So many of the community outcomes that we want to meet, food plays a role in. There is the social wellbeing side, as well as the economic development, as well as environment. It just is a touchstone for so many different areas of work.''

Last year, Mayor Dave Cull signed the Good Food Dunedin Charter to adopt the vision that "Dunedin is a thriving food-resilient city''.

The charter was created with the input of a diverse network of stakeholders and the wider community.

"We now have some action areas defined,'' Zeinert says.

These are:

• Leadership and co-ordination

Zeinert connects disparate people and groups to work together to solve problems, such as linking food-waste producers with potential users of the food waste.

• Schools at the heart

"There are a load of different agencies working in the food space in schools,'' Zeinert says. "Those agencies are increasingly proactively working together in Dunedin to maximise the opportunities for schools without over-burdening them.''

• Business support

The Good Food Charter's aspirational commitment is that food should be; good for people, good for the city and good for the planet.

"I am always highlighting to businesses that we have a charter and that this is what the community have said that they want.''

• Growing community gardens

Zeinert is looking to the Auckland Council's "Kai Auckland'' action plan, that is broadening the remit of community gardens to teach people about growing food as well as attempting to engage a diverse range of people.

"It takes lots of different touches for people to want to get involved and to feel part of something.''

Productive backyards and community gardens are faint echoes of the fruit and vegetables that used to surround and feed our once smaller cities. Our Land 2018, a comprehensive report on New Zealand's soils, shows that New Zealand has been steadily losing versatile soil under asphalt and housing as cities sprawl.

The report says that "between 1990 and 2008, 29% of new urban areas were on some of our most versatile land''. This is happening at the same time as the world's population grows to an estimated 9.8billion people by 2050. It is expected that will require a doubling of consumption of plant-foods. In response, Environment Minister David Parker has announced law changes to better protect high-class soils.

According to Otago regional councillor Dr Ella Lawton, of Wanaka, reclaiming urban land for food production may be just what the planet needs. As a PhD student, Lawton set out with her supervisors, Drs Robert and Brenda Vale, and her mother, Dr Maggie Lawton, to create the New Zealand Footprint Project, completed in 2013.

When the data was analysed, she discovered that food contributes 56% of the average New Zealander's ecological footprint.

"It was a surprise to me because it was a different spread of footprint for New Zealanders than it is for a lot of other countries,'' says Lawton.

This is largely because other countries have a higher relative impact from other sectors, such as housing, because they use more fossil fuel to heat and power them.

To reduce the food component of our ecological footprints, the footprint project identified switching to a plant-based diet, consuming less meat, dairy and fish, and eating more food grown organically, without pesticides and synthetic fertilisers. In particular, Lawton found that the average person's footprint can be greatly reduced by growing and consuming food grown close to home.

"If you're growing food in your own garden that means less land is needed to grow food somewhere else.''

In response, Lawton decided to increase her weekly food budget to better reflect the true cost of her food on the environment. She ate predominantly plant foods, bought more organic food, the meat she ate came from wild pest animals, and every now and again she even successfully speared her own wild fish. "[Spearfishing] is exciting and it really makes you appreciate life under the water.''

While working on the project, she made significant inroads into her own footprint.

"I was growing or foraging probably 60% of fruit and veg we were consuming. So I was getting there.''

Both Lawton and Reynolds have dreams of someday selling the food they grow. When she stands down as a councillor in October, Lawton will take up residence on 2ha of land near Invercargill with her partner, where they plan to grow mushrooms heated by solar power.

Reynolds is focused on fruit trees. "I've kind of got a bit of a dream of owning my own orchard and so Roimata allows me to sort of practise that and gain some knowledge around that, as well as benefiting the community.''

Since early 2018, Reynolds has widened his reach in the community by being employed through the Food Resilience Network as their community builder. The position is primarily funded by the Christchurch City Council and the Rata Foundation.

"It's easy to be doom and gloom about these issues but I do really sit in a positive place about our ability to turn these things around. There are many amazing people in this city, and around the country, doing amazing work to bring strength and resilience to our communities.''

Foods for our future

The report Future 50 Foods: 50 Foods for healthier people and a healthier planet, produced this year by German food brand Knorr and WWF in partnership with Dr Adam Drewnowski (director of the Centre for Public Health Nutrition at the University of Washington), focuses on three key factors in a sustainable healthy food system.

• Diverse food. Eating diverse foods is better for our health, and promotes diversity on farms to support biodiversity.

• Plant-based food. Animal products are both land and energy-intensive as well as associated with less healthy diets than plant-based diets.

• Nutrient-rich or nutrient-dense food. Food that is less processed, and grown in ways that generally benefit the environment.

Eco-educator, Dr Maureen Howard, selects her top five from the list of 50, and adds another cultural favourite.

Wakame seaweed. Farmed in the Marlborough Sounds where it can grow up to 1m a day. Full of micro-nutrients, seaweed is good for us as well as the garden. Collect and dry it yourself from clean ocean waters, or buy from the supermarket. Can be eaten in miso soup and seaweed salads.

Broad beans. These grow effortlessly in our cooler temperate climate. Pick when quite young and remember to save some of your best beans to dry for planting next season.

Pumpkin parts. According to Future 50 Foods, the leaves, flowers and young stalks can be eaten as well as the pumpkin and seeds. With so many pumpkin plants popping out of compost bins, pumpkin parts are definitely worth a try.

Beetroot greens. Don't throw away those tops. According to the report, they are the most nutritious part. Cook the harvested leaves and stalks in soups or stir fries.

Irish-born, Howard also promotes the potato, despite it not making the cut for the Future 50 Food list. Potatoes need less water to grow than wheat and are a good source of Vitamin C.

There are many colourful and uniquely shaped heirloom varieties to choose from, including those cultivated by Maori for at least 200 years, as well as those later brought by the European settlers.

• To see the full list, go to www.wwf.org.uk and search for "50 foods''.