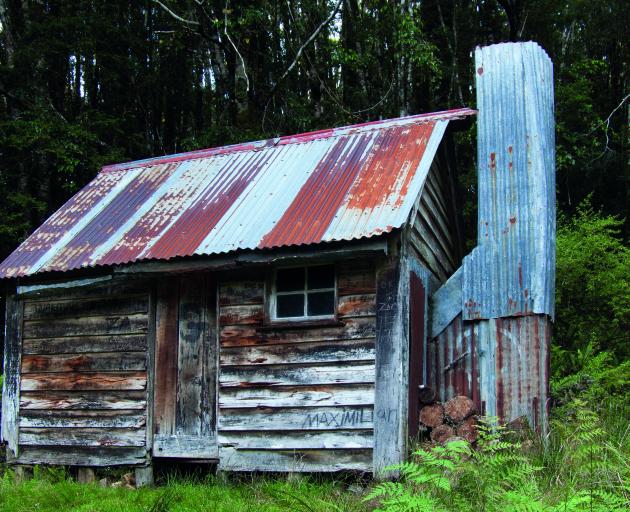

Hut, surroundings redolent of Grimm’s fairy tale

Where: Longwood Forest Conservation Area

Details: 4 bunks, open fire, historic, basic

Huts come in all styles and sizes, but few fit the classic image we have in our heads from childhood: weatherworn, rustic and buried deep in the forest. Historic Martin’s Hut does though — if you want the real McCoy, this is it. The hut and its surroundings could have come straight from a Grimm’s fairy tale. The track to it follows an old water race under a canopy of stately silver beech forest, and the hut was built to provide a home to the men who looked after the race more than a hundred years ago.

One of several water races in the area, the 24km-long Martin’s water race was built in about 1890 by Robert Erskine and Martin Anderson, while Martin’s Hut was built in 1905 by Fred Mason. From Martin’s Hut, the water race continues to Turnbull’s Dam, built in about 1898 by the Round Hill Goldmining Company. That dam also has a historic hut associated with it, Turnbull’s Hut. Martin’s water race then dropped down around the dam and continued to one of the dams near the main gold-sluicing operations.

Martin’s Hut is a typical small raceman’s hut and still largely in its original condition, except for a corrugated-iron roof that has been placed over the timber shingles. This was probably done by the Forest Service, and undoubtedly saved the hut from complete collapse. The hut is constructed of circular-sawn weatherboards measuring about 200mm by 20mm, indicating they were brought in from a nearby mill rather than pit-sawn on site.

The fastest access to the hut is from the east, via Cascade Rd. A marked Doc track leads up in less than an hour to Martin’s water race, and from there it is just a few minutes to the hut. Recently marked routes also lead from Long Hilly or Round Hill, where the mining took place, along the old water races to the hut and beyond it to Bald Hill Road Quarry, six hours’ walk away to the north. These routes are part of the Te Araroa Trail, a walking track that extends from Bluff to Cape Reinga, and some of the more recent Martin’s Hut logbook entries reflect that.

On March 8, 2012, Rob and Debbie wrote:

Very soggy track after overnight rain. Hut very welcome our last. This is our 67th night from Ship Cove, Queen Charlotte Sound. Should finish in 4 days time at Bluff Head. It’s been a great journey, Cape Reinga to here. Thanks DOC for the great tracks and huts that have made it all possible. Greetings to fellow trail walkers. Hope you enjoyed it as much as we did.

Others were just beginning the journey. But it is clear from the logbook that most of those who call in are locals, hunters after a deer, trampers keen to walk up to the tops of Longwood (764m) and others exploring the old water races that are part of their local (and national) heritage.

Approaching the hut along the water race, we arrived late one windless afternoon in February. No water flows in the race anymore, and parts of it are overgrown. The air was still and the forest drowsed in the sun. Unhooking the wire door latch, we entered, stepping on to the broad, solid floorboards. At the end of the hut stood an open fireplace, with a hearth of earth in front of it. We lit the fire and put on a billy, and suddenly the hut was alive.

As I sipped my brew I watched the evening draw down. Kaka, robins, tomtits, bellbirds, fantails, grey warblers and a weka called or visited. And then, with only the embers of the fire glowing, from the velvet dark beyond the window a morepork called. In some of these older huts the boards may be wobbly, the bunks rough and cobwebs hang from the rafters, but sleep is as deep as the stars are high.

— Geoff Spearpoint

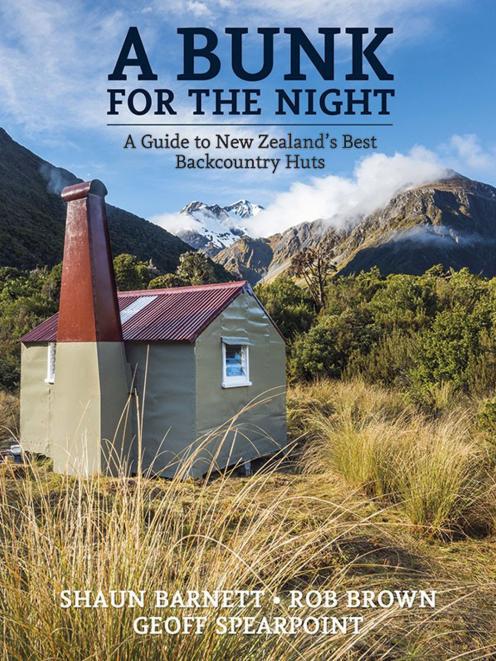

Way above Hermitage

Where: Aoraki Mt Cook National Park

Details: Sleeps about 4, no heating, basic

It is just up the hill from the Hermitage, but historic Sefton Bivouac may as well be on a different planet. Opposite, the icefields of the Tewaewae Glacier grind away, while below, the Hooker and Tasman valleys stretch to distant lakes and the plains. At night, the lights of Aoraki/Mt Cook Village twinkle away, emphasising the gulf below. And all this from a tidy little bivvy that has just passed its 100th birthday.

In 1999, Doc did a restoration . In 2019, Aoraki Mt Cook Residents Association volunteers painted it.

The inspiration for locating a hut up here at 1650 metres came from chief guide Peter Graham, who wanted to make the climbs of The Footstool and Mt Sefton easier. All the materials were carried up manually and the building took place in 1917. The floor was earth. The 1999 restoration included a wooden floor.

From the White Horse Hill campground, follow the track up the Hooker Valley. Leave it at Stocking Stream and follow the creek, which gives access to the spur the biv sits on. The route isn’t officially marked and has steep, exposed, scrambling sections on it. In summer it will take about three hours from the road to the biv.

I arrived in the afternoon, watched the sunset, then settled in with all the pleasure of being secure in a cosy bivvy overnight in May. When I woke, a fresh layer of snow sprinkled the bivvy, magically transforming the place.

— Geoff Spearpoint

Water races vital to efficient running of gold claim

Where: Blackmore Station

Details: 4 bunks, open fire, bookings required: trails@welcomerock.co.nz

Mud Hut is a historic water raceman’s sod hut that was restored in 1990 by Des O’Brien of Blackmore Station, Doc and a team of volunteers. It was probably built sometime in the early 1890s, and was located right next to the Roaring Lion water race, which diverted water down to the gold workings in the Nokomai Valley. This goldfield was one of many in Central Otago that provided employment for Chinese miners who had immigrated to New Zealand. Most goldfields needed vast amounts of water to drive machinery and pump through the sluicing guns. In Central Otago, water races were critical to the efficient running of a claim and companies employed men to maintain 68km sections.

Mining at the Nokomai goldfield started in the 1860s, but an attempt to bring water for sluicing from Diggers Creek in the 1880s wasn’t a success. The company that owned the water race extended it all the way back to Roaring Lion Creek — a major tributary of the Nevis River — but the returns in the Nokomai were not enough to cover the costs of the investment. The company was then purchased by astute Dunedin businessman Choie Sew Hoy and renamed the Nokomai Hydraulic Sluicing Company. Sew Hoy had pioneered the use of mechanical dredges to access the bed of gold-rich rivers. His first venture had been with a small dredge on the Lower Shotover River, and almost immediately it started paying for investors. Sew Hoy died in 1901, just as the Nokomai was at its peak production, but his grandson Cyril Sew Hoy took over the company and ran it successfully through to World War 1.

At one time there would have been perhaps half a dozen men maintaining the Roaring Lion water race. From Mud Hut, they could easily monitor the flow — whenever it slowed they would walk the race, clearing out debris, patching leaks and improving it until the flow became more efficient. There are the remains of at least one other raceman’s sod hut in the area, along the side of the Welcome Rock Track. This is Lee Lum’s Hut (1925), and is not far from the saddle that separates the Nevis and Nokomai Valleys.

Many of the Chinese prospectors on the goldfield worked here only during the warmer summer months; in winter they would head back to Dunedin. Many had wives back in China, to whom they would send a portion of their earnings, and nearly all cooked themselves traditional Chinese food from ingredients imported by the same businessmen who employed them on the goldfields. Some Chinese miners would die here, too, either through work accidents or simply old age. Today, the small cemeteries of Garston and Nokomai are a sombre reminder of the hard life endured by the ancestors of Otago’s contemporary Chinese community, who struggled to establish themselves in this new land.

For many years Mud Hut was just a derelict part of Blackmore Station’s landscape. Times were tough after World War 2, and with iron in short supply the roof of the hut had been salvaged to help repair the woolshed. Like many sod huts, once the weather got in it started to deteriorate quite quickly. By the late 1980s, the hut had partially collapsed, but its value was recognised by Doc. Together with the O’Briens, they decided that a total rebuild was the best way of preserving what was left. Twenty square metres of sod were cut from the surrounding tussock

tops to rebuild the walls,

after which the structure

was reroofed. It’s a magnificent example of how to sensitively restore a hut that has lost large amounts of its original structure.

In 2012, Des’ son Tom decided to develop a high-country mountain-biking and walking track following the water race and making use of a combination of new and historic huts. Welcome Rock Trails was opened in 2013, and has been a great example of how to combine historic sites with interesting new recreation opportunities.

— Rob Brown