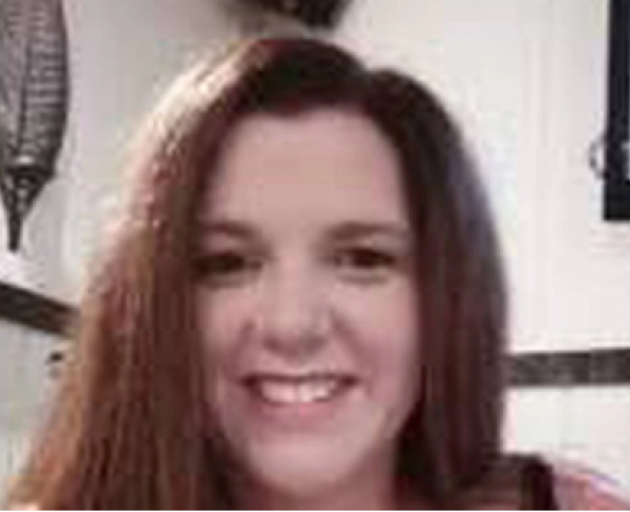

Joanne Rachel Dening died after falling off a stand-up paddleboard (SUP) at the Wenderholm Regional Park, north of Auckland, despite the attempts of several people to save her.

"She was a lovely person, a marvellous teacher loved by all her pupils."

But despite her confidence in the water she wasn't able to get to safety after falling from her SUP in February 2019.

Coroner Katharine Greig has ruled a combination of factors contributed to the Englishwoman's death, including the use of the wrong leash, the fact she didn't have a personal flotation device (PFD) and was in conditions outside her ability.

The coroner said her death highlighted the dangers of the sport and the need for education.

Dening had recently returned to New Zealand after visiting her parents, family and friends in the United Kingdom for Christmas when her flatmate Lorissa invited her to go paddleboarding.

It was her day off and Lorissa knew her flatmate had previously wakeboarded and thought she might enjoy giving SUP a go.

Lorissa described Dening as being excited to try the new sport and had organised for her to use her boyfriend's SUP.

They arrived at the park, on the southern side of the Puhoi River, at about 11am. The weather was fine and there was no wind.

The river runs into the Hauraki Gulf, which borders the eastern side of the park. The boat ramp at the reserve leads to a large estuary, fed by the river, with a channel to the Gulf.

Their plan was to launch from the boat ramp into the river and paddle from the estuary into the channel on the outgoing tide, then paddle round the beach area.

Lorissa said Dening was quickly able to stand on the board and paddle around.

The pair paddled off together, slowly, towards the mouth of the estuary to go into the bay where Lorissa said the water was very calm and reasonably clear.

However, as they paddled across the channel the water became more turbulent and a strong current was flowing.

Two witnesses watching from the shore described the women as moving fast with the current which they said was "really streaming out" and the fastest they had ever seen it.

"They described one of the women as wobbling and not looking confident," Coroner Greig said in her findings.

Lorissa watched as Dening lost her balance, fell into the water and was pulled along by the current towards the channel marker.

Dening tried to reach for her board but her leg rope got wrapped around the marker with her on one side and the paddleboard on the other.

"Lorissa said that she could see Ms Dening trying to swim against the current towards the marker so she could undo the leg rope, but the current kept pulling her under the water," Greig said.

Lorissa tried to paddle back to Dening, but the current was too strong. Instead, she paddled towards the beach to raise the alarm and asked a member of the public to call emergency services.

A kayaker, who saw Dening fall, went to her aid.

"As he got closer, he could see Ms Dening bobbing up and down struggling to breathe."

When he got closer Dening was not responding to his calls, so he gripped her by her armpit and pulled her up out of the water.

"She then grabbed the kayak with both her hands and the kayaker told her she needed to hold on to the front of the kayak. She responded to the kayaker saying she needed to rest."

As Dening was holding onto the kayak, it started to pull into the current and water started pouring in, causing the kayak to flip.

Dening let go of the kayak and the kayaker went into the water. Unable to swim against the current to get back to her, the kayaker swam towards the beach holding on to his kayak.

As he got close to the beach, after being in the water for about 20 minutes, a commercial fisherman came to his aid and he explained what had happened.

The skipper then headed to assist Dening but said there was "a lot of rip that was really obvious" and that it was the second day of the biggest tide of the year.

He found Dening on one side of the channel marker and the paddleboard on the other but could not help her on his own.

"One of her legs was tied to the board and Ms Dening's body was underwater."

After picking up a member of the public they together went back and cut the leg rope and pulled Dening onto the boat and took her back to shore.

Ambulance Officers provided first aid to Dening but she did not respond and was pronounced dead at the scene.

A post mortem examination found she drowned.

A Maritime New Zealand report stated "given the expanse of the estuary at high tide, in flat conditions and with minimal wind it would present as an area where it could reasonably be expected people may use stand-up paddleboards, including beginners in the sport such as Ms Dening."

The report noted Dening was using the wrong type of safety leash, according to the New Zealand Stand-up Paddling (NZSUP) Safe Code.

NZSUP states that only a leash with a quick release system that can be operated above the waist should be used in the conditions and a leash attached to the ankle or calf should never be worn in moving water.

Dening was not using a personal flotation device, which was also in breach of the NZSUP code and maritime rules.

The report, however concluded it could not be known what impact wearing a PFD would have had in the situation, with the fast-moving current and the different types of PFD available.

Coroner Greig found the planned excursion was not a reckless expedition and there were many factors that made the sport a natural fit for Dening.

"She was fit, a strong swimmer who was confident in the water, she had experience of a number of water sports."

However, with the benefit of hindsight and expert advice, the coroner reached the view Dening's death was preventable.

Dening was using the incorrect leash, which she and Lorissa were unaware of, she was in conditions outside her ability when she left the estuary and entered the channel, and she did not have a PFD.

Coroner Greig recommended the Auckland Council erect signs at the boat ramp warning of the dangers of strong currents in the channel, the presence of marker buoys in the channel and the need for extra care around the buoys, which had been accepted.

Consultation with the Auckland harbour master to identify other locations where the same set of hazards exist and where new signage should be implemented should also continue.

She also recommended Maritime New Zealand post safety information on social media about the lessons learnt over the circumstances of Dening's death.

"Ms Dening's tragic death arose, as so many unexpected and unintentional deaths do, when a constellation of potential risks associated with the activity she was undertaking crystallised with fatal consequences," Coroner Greig said.

"At the core of preventing deaths in similar circumstances is the need for accessible and widely disseminated safety information relating to stand-up paddleboarding."