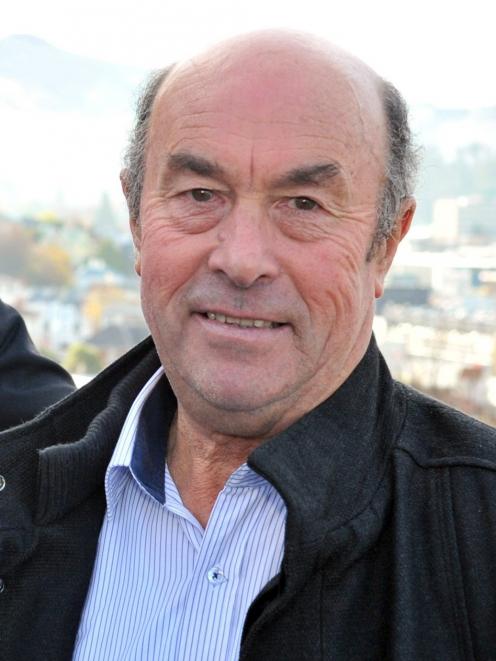

Te Anau community stalwart, 90-year-old Fred Inder died alone. It is something his family could not change and will never forget.

The former harbour warden of 27 years and recipient of a "local heroes" award died on March 25 — the day the country’s Level 4 Covid-19 restrictions began.

The situation has tormented Mr Inder’s daughter, Viv Tamblyn, who said she had promised her father she would not leave him alone as his health deteriorated.

She was able to " view" his body — two people at a time in full protective gear, maintaining social distancing — to say a goodbye, but it was scant consolation.

"[It was] heart-wrenching to watch family members in tears and not being able to give them a hug," Ms Tamblyn said.

As Mr Inder’s health deteriorated, advice changed rapidly — from the possibility of a funeral with fewer than 100 people, to one with a couple of family members, to none at all.

This week, the Ministry of Health updated restrictions so that people from a deceased person’s bubble were now able to view the body.

But it will no doubt be some weeks before funerals and memorials would be permitted. "Covid-19 robbed us of a fitting farewell to a man who was so community-minded," Ms Tamblyn said.

Mr Inder’s son Garry said the fact the family had not been able to grieve together had been the hardest to take.

"The first thing you want to do is rip a bottle of gin open and let it all out," he said.

"You have a [laugh] and a cry and get it out of your system."

Mr Inder — whose list of community involvement was huge and varied — was cremated, and family said they planned to hold a memorial service months after restrictions were lifted.

Dunedin funeral directors told the Otago Daily Times that had been the most common option taken by those placed in such traumatic circumstances.

Hope and Sons Funeral Directors manager Andrew Maffey said the past two weeks had been "a steep learning curve", and he continued to field a flurry of calls from people concerned about the limitations they faced farewelling loved ones.

The severity of the situation was made clear when police and disaster-response officials contacted the business asking about their storage capacity for bodies — part of worst-case-scenario planning.

Mr Maffey said staff had been split into four bubbles so if anyone contracted the virus, only their immediate colleagues would have to self-isolate.

Hope and Sons, which conducts 40 to 50 services a month, had had to improvise.

Mr Maffey said they were now offering "video viewings", in which they would film from a first-person perspective.

The challenge was "doing it as tastefully and respectfully as possible", he said.

Like those in the health sector they had experienced a shortage of personal protective equipment, to the point where one of the more practical staff members had started making face masks from scratch.

"For us as a staff it is gut-wrenching not to be able to give people the services we normally provide. We’re so proud of being able to say yes to whatever people want to do," Mr Maffey said.

It was a similar sentiment expressed by Gillions Funeral Services director co-owner Elizabeth Goodyear, who described the situation as "heartbreaking".

"It’s daunting. I guess there are so many unknowns," she said.

Ms Goodyear had already had to cancel a couple of funerals planned for last week, which had taken a heavy toll on bereaved family members.

Public services, she said, were such an ingrained part of the grieving process that people felt lost when that opportunity was removed.

"Everyone wants to hug each other; people cry," Ms Goodyear said.

"You lose someone you love and you’re not able to do what is our completely natural human instinct, which is to gather together and hug and grieve and remember and celebrate ... That choice is taken away."

Gillions too was looking at remote viewings and had increased referrals to a grief-counselling service in Auckland.

While for Pakeha, the situation was dire, for Maori it was even more pronounced.

Otakou marae upoko Edward Ellison said tangihanga protocol dictated a body should not be left alone until burial.

It would usually begin with the deceased being at home before being transported to the marae, before interment.

One of the key elements of tangihanga, Mr Ellison said, was that people would come and go, support the whanau and share stories about the person.

"All that helps the family in their grieving and in their time to say farewell," he said.

"There’s no rush about it — it’s an unfolding of that person’s life before you."

However, under Level 4, that tradition was now impossible.

Mr Ellison said they had been distributing "tikanga guidelines" by email so the community could be prepared if tragedy struck.

One alternative suggested had been "kawe mate" — a format used when a body was not available to a grieving whanau.

They would carry photos of the deceased on to the marae in a ritual Mr Ellison described as similar to a powhiri.

Whatever happened with Covid-19, he said he was confident in the resilience of community.

"People find ways of dealing with it and we will get through — tikanga can be flexible," he said.

"It may be very difficult for family immediately, but we’ll find a way to come together and help them."

Guidelines

Ministry Of Health guidelines (under Level 4)

- Only registered funeral directors can carry out burial, cremation or transportation

- of deceased.

- Funerals not permitted.

- Funeral directors must carry out burial or cremation "as quickly as possible".

- Live streaming or photos of burial/service can be provided by funeral directors.

- Families encouraged to hold memorials once restrictions around gatherings are

- lifted.

- Only those from same isolation bubble can physically view body at funeral home.

- Premises must be sanitised after viewing.

- Religious rituals may occur, strictly under supervision of staff.

- Funeral directors must keep a log of names and contact details of people who view body