Iain Chambers (ODT 21.1.11) drew attention to the interface between science and theology, mentioning a number of distinguished scientists who have contributed to the debate.

Some argue from the atheistic or agnostic viewpoint, but a surprising number put the case for theism.

Many of them have been prompted to respond to the increasingly strident outpourings of the distinguished Oxford biologist Prof Richard Dawkins, and it is interesting how many of his more acute critics also call Oxford their academic home.

Of these, I have found particularly helpful the mathematician Prof John Lennox. In his book, God's Undertaker: Has Science Buried God?, Prof Lennox performs two services for all those who, in reflecting on the great issues of life, the universe and everything, wish to heed Socrates' famous exhortation to follow the evidence wherever it may lead.

First, he redefines the basic issue in question; and secondly, he provides his readers with the scientific evidence they may wish to follow in their own search for ultimate truth.

Prof Dawkins likes to portray the relationship between scientists and theists as that of unyielding combatants forever locked in an unholy war.

In one armed camp he would place the entire community of scientists, whom he is pleased to think of as men and women who are dedicated to the search for objective rational truth and who, therefore, have long ago rejected all such nonsense as belief in God, fairies at the bottom of the garden and anything else with the slightest whiff of the supernatural about it.

Opposed to them he posits another group comprising all those pathetic people who, for some inexplicable reason, refuse to be convinced by the arguments of the good professor and his allies and still cling to some form of religious belief.

Prof Dawkins is convinced that the tide is running very much in favour of the scientific community: as science triumphantly advances with each new wonderful discovery, God is forced to hide his fast-fading glory in fewer and fewer gaps in our knowledge.

So believes Prof Dawkins, but his Oxford colleague, Prof Lennox, will have none of this. For him, there is no fundamental divide between science and theology. How else to explain that some of the greatest scientists working today are avowedly Christian, and some of the greatest theologians are also accomplished scientists?

The true clash, according to Prof Lennox, is one of world views, which he calls "naturalism" and "theism".

Naturalism holds that nature is all there is: there is no transcendence, nothing supernatural. Theism holds to the contrary: nature is not all-encompassing and self-explanatory. It requires some outside agency to explain its very existence. Not just how it came into existence, but also why it came into existence.

Prof Lennox poses the central question in the form of a direct challenge to the scientific community (as well as the rest of us): "Which, if [either], of these two diametrically opposing world views of theism and atheism does science support?"

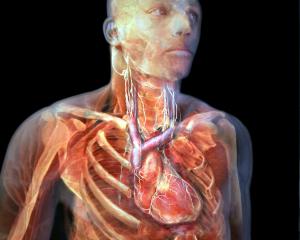

And in the core of the book he takes us on an evidence-gathering tour of the relevant sciences - physics, chemistry, biochemistry, biology, mathematics and information science - to help us answer that question for ourselves.

He draws our attention to a number of fundamental questions that seem to defy scientific answers. These include the origin of the universe, its rational intelligibility, the extraordinary degree of "fine-tuning" that has rendered the universe fit for life, the origin of life, origin of consciousness, origin of rationality and the concept of truth, and the origins of aesthetics, morality and spirituality.

Above all, he asks why it is that wherever we look - at the cosmic level, the microscopic level or anything in between - we are confronted by what appears to be overwhelming evidence of intentional design?

While hard going, this tour was worth the struggle, particularly when Prof Lennox brought the insights of microbiology, biochemistry and information science to bear on DNA.

All life, it now seems clear, is information-based. We might say it is "in-formed". St John the Evangelist had the same idea 2000 years ago when he began the Fourth Gospel in this extraordinary way: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life."

Substitute DNA for Word, change the masculine pronouns to neutral, and be amazed.

St John was writing in Greek, and in that language the word translated above as "Word" is "Logos", much used by Greek philosophers of the classical period to signify the rational principle that they discerned in the universe.

Leading American biologist Francis Collins, in his book on DNA entitled The Language of God, puts that old word to new and fascinating use. He rejects all such terms as creation and intelligent design because of the anti-intellectual baggage they carry. His preferred term is "Biologos" - Bios [life] through Logos [Word].

The author of the magnificent opening chapter of the Book of Genesis would say Amen to that. What Prof Dawkins would say to that is probably unprintable.

• Roger Barker, of Waikouaiti, is a recently retired Anglican priest and former parliamentary counsel.