Healing and health, holy and wholeness - the words have common or linked origins and are integral to the Judaeo-Christian tradition of faith, suggests Ian Harris.

If you're dissatisfied with your job and not particularly happy with life anyway, be very careful around 9am on Mondays.

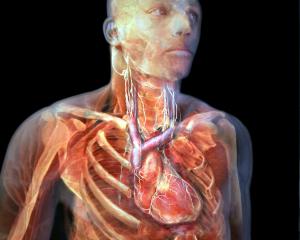

A United States study suggests this combination could put you in line for a heart attack.

Researchers into the so-called Black Monday syndrome found there were more fatal heart attacks at the start of the working week than at any other time.

People who loathe their job and dread going back to work after the weekend are not in a healthy space.

The syndrome underlines the well-known interplay between a person's state of mind and his or her physical health.

That link is embedded deep in the language of medicine and religion.

To heal is to make whole; and linguistically, wholeness includes the dimension of the holy.

That is because all those concepts spring from the single Old English word hal, meaning free from injury or disease, safe, sound or well - in short, hale as in "hale and hearty", which in southern dialects became "whole".

The connection suggests that body, mind and spirit are not sealed off in separate compartments, but the wellbeing of each of them is inextricably tied up with the others.

Just as bodily pain can affect people's outlook on life and put them in low spirits, so mental stress can work its way out in physical ailments or noxious behaviour.

Lack of wholeness carries a cost both for individuals and the people around them.

So it is healthy (another word from hal) to aspire to wholeness, and unhealthy to pretend that positive values and attitudes do not form an essential part of a wholesome (another derivative) mix.

It is important to reflect this in setting life goals.

For many people, getting a good job, having a family and paying off the mortgage loom large at the outset.

Ideally, however, such goals belong within a broader, life-long effort to integrate our physical, mental and spiritual wellbeing.

"Integrate", of course, means to make whole.

That happens all the time, though only rarely does it make the headlines.

An exception was a newspaper report a few years back headed "Infant's killer finds God".

It told how Brownie Walter Broughton had confessed that it was he, not his partner, who shook their 7-week-old daughter to death 13 years earlier, though his partner shouldered the blame at the time.

A court in Auckland heard he was moved to do so by his new-found faith in God.

He accepted his three-year jail sentence for manslaughter as the price of his atonement.

This points to another word derived from hal and highlights its relation to healing, health and wholeness: holy, from the Old English halig.

In its earliest uses the word refers to things which must be preserved whole or intact, or which cannot be injured with impunity.

It was used especially in connection with the gods and, after Christianity came to Britain, with God.

In our secular society, the purely religious association needs to be filled out by linking holy with the other hal words.

Mr Broughton's experience suggests that conscience cannot be injured with impunity: his sense of the holy led him to seek the healing of an old wrong, bringing with it the promise of wholeness.

And when a doctor advises a patient to take a holiday for the sake of his or her health, the same connection lies just below the surface.

A holiday was originally a holy day and holy days and holidays can contribute enormously to mental and physical health.

For thousands of years, religions have provided rich and accessible resources for healing at depth, a healing related to holiness and wholeness.

Sometimes, however, those religions become sclerotic and ridden with superstition, diminishing their power to convince.

By the same token, a vibrant faith tradition that evolves with the culture still offers a dynamic and a focus for the wholesome integration of our total experience of living; and at its best the Judaeo-Christian tradition is still capable of doing just that.

Properly understood, the tradition promotes a sense of identity and worth for both individuals and groups.

It provides a framework of meaning and purpose for living.

It fosters a trusting orientation to life and its possibilities. It encourages values and attitudes that further the good of society, offers a way out of guilt and apathy, and gives hope for the future.

In short, the Judaeo-Christian faith tradition liberates, energises and makes whole - and if it does not, it is not the real thing.

- Ian Harris is a journalist and commentator