After much consideration and bucket-loads of tears, I decided to switch courses to English literature. My relief was immense. But now I had the task of deciding which classes to take.

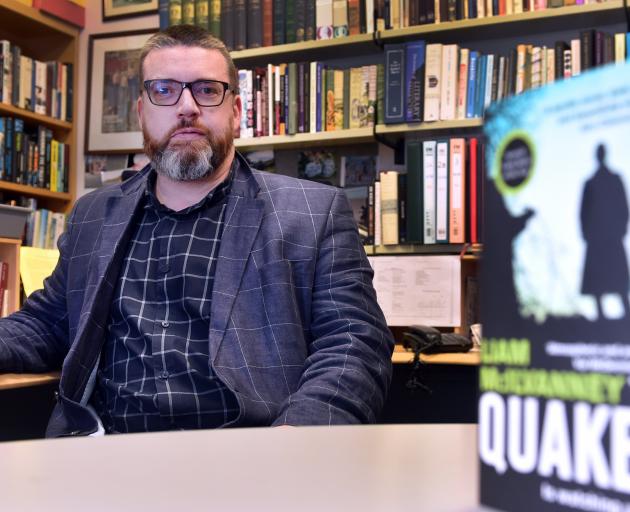

Although I hadn’t yet studied English literature at a tertiary level, I was allowed to take part in a second year course with Prof Liam McIlvanney: ENGL243 Tartan Noir: Scottish Crime Fiction. The title intrigued me, and the course description even more so: "An exploration of the long tradition of ‘tartan noir’, from the ‘classic’ crime fiction of R.L. Stevenson and Arthur Conan Doyle to contemporary thrillers and police procedurals." My father’s grim recollections from his upbringing in Glasgow, coupled with the ghost stories he told us around the dinner table prompted me to attend these classes.

The reading list was extensive, ranging from Sir Walter Scott’s short stories to Muriel Spark’s enigmatic novellas to Val McDermid’s thrilling novels. I stayed up all night, soaking in the gory details. I learned about old Highland ways of restoring one’s family honour, how a murder victim’s face might resemble the smeary mess of a Francis Bacon painting and how to properly clean a crime scene. The class was fascinating, and I discovered a love for a genre I had previously overlooked.

The genre of crime fiction is often disparaged, or considered less than literary. One of my theories is that many crime novels — I think here of the lurid reads displayed in airport shops — tend to focus more on "whodunnit" rather than "why-they-dunnit". But there are plenty of brilliant novelists who can both structure a compelling murder mystery and create emotionally complex and multifaceted characters. I have enjoyed charting the trajectory of Ian Rankin’s jaded Detective Inspector John Rebus over the years, as he is faced with new challenges in life, both personal and work-related (and often both).

It seems as though only a handful of crime novelists have propelled their books to the status of "classic". We have, of course, Agatha Christie, the "Queen of Crime", Arthur Conan Doyle and Raymond Chandler. But in the UK at least, one in every three books sold is a crime novel. Crime fiction is an enormously popular genre and I have immense respect for those authors who can craft an unputdownable tale. I also love the fact that most literary detectives are brilliantly eccentric characters; often flawed, if not fatally flawed. Philip Marlowe, Inspector Morse, and their ilk provide us with an inside (albeit sometimes fantastical) glimpse into how crimes are handled and solved.

Crime fiction also translates wonderfully to the big screen; consider the brilliance of The Silence of the Lambs, or the sheer power of No Country for Old Men. The moment of realisation; the "clink" of the penny dropping for the audience is powerful indeed, eliciting gasps from the cinema audience, and cries of astonishment. The desire to know "whodunnit" and why is strong, and when satisfyingly fulfilled, there is a palpable sense of satisfaction and relief.

Sometime I wonder about the real-life ramifications of crime novels. Do villainous readers ever flick through the pages of Iain Rankin’s latest thriller to pick up tips on creating the perfect murder? I think here of Donna Tartt’s spellbinding story of undergraduate murder, The Secret History, in which a group of college students get away with slaughtering one of their own. Is there the danger that such books might act as blueprints for wannabe-murderers? And what happens to the real-world locations of grisly literary deaths and assaults? Will your story about a serial killer dissuade people from settling in that part of town?

I also wonder whether reading too many gory tales of murder might desensitise me to the tragedies unfolding in the world beyond the dust jacket of my latest book. I will also admit that historically, crime drama has its issues. The pages of classic detective novels are littered with the dead bodies of women, sex workers and transgender people.

More often than not, I’ll pick up a crime novel to discover that the victim is yet another beautiful dead woman. Sometimes I shudder at the atmosphere of necrophiliac excitement conjured up by the (usually male) author as he describes his victim.

But conversely, the majority of crime fiction readership is now female.

Moreover, female characters are beginning to dominate the genre, especially with the rise of "domestic noir", a genre of crime fiction wherein the most severe atrocities are committed within the domestic sphere, often by jilted wives.

I wonder if the uncertainty occasioned by the worldwide pandemic has awakened in us a new-found desire for order, resolution, dedication and redemption.

Perhaps crime fiction can distract us from the chaos in our personal lives by providing us with a strong and compelling narrative that we can hold, both literally and figuratively, at an arm’s distance.

For now though, I’ll curl up in bed with my next read: The Quaker, by my former lecturer, Liam McIlvanney. No spoilers please!

- Jean Balchin, a former English student at the University of Otago, is studying at Oxford University after being awarded a Rhodes Scholarship.