What exactly is this month's election about? If you answer: "Deciding who will run the country for the next three years", you'd be right, but only at the level of the bleeding obvious. There is more to involvement in a healthy democracy than determining which of the contending voluntary clubs, aka political parties, should be entrusted with governing us.

If you say: "Voting for the party that will do the most for me", you have sold out to a self-centred individualism that bodes ill for New Zealand's future.

How about: "Electing the party that will do most to boost my business, profession, charity, association, cause or race"? That widens the focus, and any benefits may well extend beyond your particular group. But it still smacks of the good of a sector rather than the good of the whole.

Well, then: "Backing the party that seems best equipped to manage the economy." That will sway those worried about debt, rising prices, unemployment, tepid investment and growth. However, there is more to society than the economy. Costs and benefits are to be measured by social and environmental effects as well as financial.

So while economic management will always figure large in election debates, it is only one aspect of a much bigger picture - a picture which for many people religion once provided. But as the churches recede from any major role in political inspiration and debate, that picture has become blurry.

In June, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev Rowan Williams, highlighted the difference this bigger picture could make, as he challenged British Government plans to transfer many responsibilities of central government to local communities, charities and private organisations.

Not so fast, said Archbishop Williams. Such a shift should not be contemplated without wide democratic debate. And central to that debate is the question: What kind of community do people want to live in?

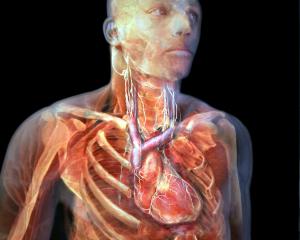

For him, the answer lies in sustainable communities, which he described as communities in which "what circulates - like the flow of blood - is the mutual creation of capacity, building the ability of the other person or group to become, in turn, a giver of life and responsibility".

He added: "This is what is at the heart of St Paul's ideas about community at its fullest: community, in his terms, as God wants to see it."

Where that is the focus "the central question about any policy would be: How far does it equip a person or group to engage generously and for the long term in building the resourcefulness and wellbeing of any other person or group?"

The State cannot create such communities by decree. But it can certainly foster them through its programmes on work, education, children, health and housing.

Individuals cannot create them unless they share both a desire for them and a vision of how to achieve them. Integral to that is people's willingness to accept responsibility for their own well-being to the full extent each person is capable of, and then to contribute to building the capacity of others.

Without such a vision of sustainable and mutually supportive communities, economic priorities dominate, greed has free rein, and society moves inexorably towards fragmentation.

Last May, American Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz noted the growing concentration of wealth in the hands of an elite few in the United States, accompanied by widening inequality in the country at large.

"The upper 1% of Americans are now taking in nearly a quarter of the nation's income every year," Prof Stiglitz said. "In terms of wealth rather than income, the top 1% control 40%."

This would have consequences: "Of all the costs imposed on our society by the top 1%, perhaps the greatest is this: the erosion of our sense of identity in which fair play, equality of opportunity and a sense of community are so important."

Since the 1980s, New Zealand has also experienced growing inequality, as measured by the growing gap between the incomes of the top 20% and the bottom 20%. Fair play, equality of opportunity and a sense of community have all suffered.

A priority now is to put in place better opportunities for all children through programmes that give practical support to struggling parents, backed by long-term health and education emphases (and funding) designed not just to prop up, but to help them flourish.

Parties that resist any role in building sustainable communities along the lines described by Archbishop Williams are only contributing to the problem.

• Ian Harris is a journalist and commentator.