Is Western democracy dying? A central plank of modern Western civilisation is the belief in democracy. But a well-functioning democracy requires a degree of shared national values and inclusive prosperity. It requires the widespread belief that things will improve for most citizens. That progress will continue.

From a national perspective, this progress has historically taken the form of economic growth and higher living standards for most people.

The measurement of this progress became formalised in the 1930s with the development of national income accounting, which produces statistics such as GDP. This measures the value of national output and income. But it doesn't measure how this income and output is shared in a society.

The healthiness of modern democracies is closely linked to the shared belief that broad economic progress is the norm. If this belief is shattered, as occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930s, democracy becomes vulnerable to challenges from other ideologies, most ominously totalitarianism.

It is often forgotten how attractive fascism and communism were throughout most Western societies during the depths of the Great Depression. They were seen as very credible alternatives that could solve the economic malaise. History would reveal they were cruel and brutal chimeras.

The golden period of modern democracy was the post-war period. From the 1950s through to the 1980s there was a shared belief democracy was a fundamental aspect of Western civilisation. It was regarded as the norm of a civilised society.

There were probably several reasons why this belief was so powerful. World War 2 had revealed the horrific excesses that could be committed by totalitarian regimes. In the post-war period the voting franchise in most Western societies was universal, ensuring a sense of inclusiveness.

There was also the effects of the Cold War. The liberal freedoms of the West were hugely appealing compared to the harsh bleak constraints of communist states. It was ``us versus them'' and they didn't have free democracies.

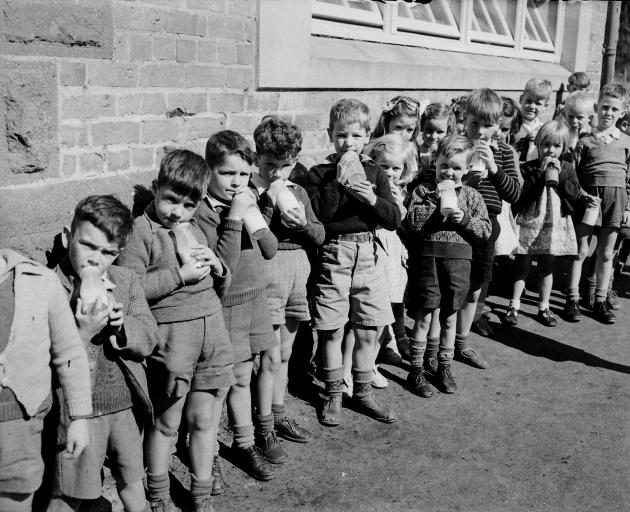

But probably the greatest bulwark of democratic enthusiasm during this period was widespread improvements in living standards. People were earning more and consuming more. They were optimistic about the future.

They were living far better material lives than their parents. They had greater access to cars, fridges, housing, travel, medicines, TVs, air conditioning, dual-flush toilets that would have been unimaginable to previous generations.

Although it wasn't utopia, it was generally an age of optimism regarding economic progress. Democracy was regarded as a natural part of this recipe for a better life.

If a healthy democratic system requires a healthy inclusive economy and widespread optimism about progress, then Western liberalism may be in dangerous territory. Trump and Brexit were not anomalies. They were products of what has been described as the elephant of modern global capitalism.

The body of the elephant is made up of inhabitants in countries such as China, India and Southeast Asia. Their standard of living is rising rapidly.

The lower part of the elephant's trunk is the middle class and those below them in the West. Their real incomes are either stagnating or declining. Their jobs are being casualised or outsourced to developing economies. Their jobs are also being displaced by technological advances. Their wage bargaining power has diminished. The young women employed in the typing pools 30 years ago are now a distant memory.

The top of the elephant's trunk are the fabled one percenters. They are the elite. They are either the skilled, talented and entrepreneurial or lucky in their choice of parents. They may have got there on their own merits and hard work or they may have won the lottery of birth.

The key tenets of modern capitalism and globalisation are free trade, free capital flows, deregulation and reduced government services and intervention. The implicit role of the state in protecting its citizens from the harsher realities of a free-market system has been considerably eroded in recent decades.

Modern capitalism and globalisation has helped raise the living standards of hundreds of millions of people in the developing world in recent decades. But as a growing proportion of Western societies lose the sense of shared national prosperity, the threats to democracy will continue to mount. The siren calls of populists and demogogues will sound more and more appealing.

Western democracy has never been the natural political order throughout human history. It was the outcome of hard-fought battles. Its biggest threats may prove to be apathy, indifference and ignorance.

Peter Lyons teaches economics at Saint Peter's College in Epsom, Auckland, and has written several economics texts.