At a Royal Society meeting in Wanaka last week, the man behind Lake Wanaka’s Grebe project was made a Companion of the Royal Society of New Zealand (CRSNZ) for a lifelong passion for conservation and science.

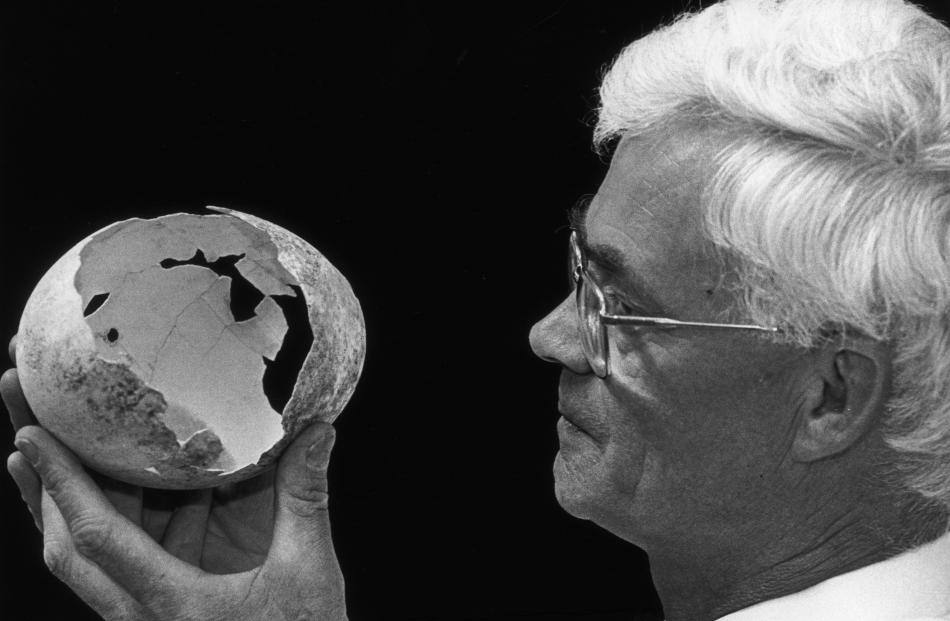

It was yet another award to add to the many 81-year-old John Darby has garnered over more than 60 years of scientific endeavour.

Kerrie Waterworth backgrounds the zoologist.

Five years ago, retired zoologist John Darby needed a break from a morning spent summarising scientific data on Antarctic penguins at his home in Wanaka, so he went for a walk along the lake shoreline. As Mr Darby wandered past the mallards and gulls, a solitary majestic-looking diving bird caught his eye.

With its slender neck, sharp black bill and distinctive black double-crested head with bright chestnut and black cheek frills, there was no mistaking it was the rare and endangered Australasian crested grebe. (Crested grebes are extinct in the North Island and are endangered in the South Island due to predation by stoats and ferrets, loss of shoreline nesting habitat and disturbance by power boats.) Mr Darby had never seen a grebe except in books but, when he later heard of one attempting and failing to breed among the boats moored at the Lake Wanaka marina, his scientific interest in ethology or the study of animal behaviour was piqued.

"As a behavioural ecologist it was so interesting to me. Could we modify the behaviour of these grebes to breed successfully on Lake Wanaka?"

For the next few months, Mr Darby read everything he could find about grebes and spent more than 100 hours watching and documenting the behaviour of these water birds on Lake Hayes.

"I had a feeling if we could build artificial nest sites near the marina, and use what’s known as the ‘supernormal stimulus’ such as making the nests bigger and more enticing, it would work."

Word spread via a weekly column in a free newspaper, the Grebe project was born and Mr Darby and volunteers made and placed floating wooden platforms around Wanaka marina. Since that time, the grebe population on the whole of Lake Wanaka has grown from six pairs with a very high failure rate to 70 breeding attempts and 153 chicks fledged from the marina.

"Everybody said to us you couldn’t do it, it wouldn’t work, but I used what I call ‘gamekeeper thinking’, where you try to think like the birds and work out what’s best for them."

Working out what would be best for himself was what made John Darby decide to emigrate to New Zealand.

He was born near Huddersfield, in Yorkshire, and spent his childhood in seven different orphanages, often running away to try to find his mother.

The countryside was the only place where he found peace and it instilled in him a love of natural history which stayed him for the rest of his life.

The young John Darby knew he wanted to be a zoologist from the age of 10 and, despite doing very well at school, he left when he was 14 years old "because in those days if you were brought up in orphanages, girls became domestics and boys became farmhands."

It was a talk by a visiting staff member from Lincoln College that led to the 17-year-old farmhand being sponsored by the college and a boat ticket to start a new life in the colonies.

"When I left England I was very angry, I had a lot of emotional baggage and I hadn’t managed to find my mother, so I made a decision when the boat docked in Wellington on May 17, 1954, to put it all behind me and start a completely new life."

He said he could still remember the sight and smell of that cold winter’s morning and of being surprised at how healthy everyone looked, particularly the children.

"I’d lived through the war and food rationing and when I arrived in New Zealand I was about 55kg and a skinny 1.77m, but in those first few years I grew more than 10cm."

In his first week at Lincoln, Mr Darby started night school in Christchurch but when he had to work on the college dairy farm he found he was milking cows when he should have been studying for the school certificate.

Mr Darby left Lincoln College for a job in the North Island where the polytech was close by.

Three weeks later he woke up in Ward 22B Auckland Hospital, a victim of the last polio epidemic to hit New Zealand.

He spent seven months in that ward before being moved to the Duncan polio hospital near Whanganui, arriving with calipers on both legs up to his hips. Finally, four months later, he was discharged with just one small caliper on his left leg.

The physicality of farming was no longer an option so he returned to Lincoln College and completed a diploma in agriculture before moving to Ruakura animal research station near Hamilton for a job as a livestock instructor.

"A week after I arrived they were putting together a team of international scientists to investigate facial eczema, which was a very serious disease in livestock at the time. They advertised for a technician, I applied for it and got it and for the first time in my life I was in science heaven. It was a mixture of field work and laboratory work and I just loved it."

It was during his three years at Ruakura Mr Darby took his first-ever holiday, hiking and climbing the Southern Alps with a male colleague.

"Somewhere in a glacier on Mt Sefton is my last remaining caliper. I’d become very dependent on it but the reality was I didn’t need it anymore."

Mr Darby returned to Christchurch to start a degree in science, met his future wife, who was a zoologist at Canterbury University, and had his first birthday cake when he celebrated his 27th birthday.

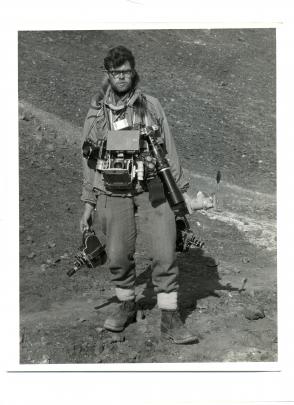

The cost of living was higher than expected, so Mr Darby got a job in the university zoology department as a technician and later developed expertise in photography.

The degree was shelved when he was invited to take part in the original aerial survey of the wildlife of the Ross dependency in the Antarctic, conducted by Dr Bernard Stonehouse.

Mr Darby spent the next three summers in the Antarctic, eventually becoming the deputy leader of Canterbury University group.

"I was very involved in some of the studies going there, particularly those on Adelie penguins, and I did a lot of filming down there. Some of my footage was used by David Attenborough in his first Planet Earth series."

On his return to New Zealand, Mr Darby successfully applied for a curatorship at Otago Museum in Dunedin and was appointed a scientific officer a year later.

Two years later, he was made assistant director and was responsible for much of the day-to-day running of the museum.

"I had a vision that instead of people coming to the museum, we make the museum part of the community and go out to them."

Mr Darby created the first Young Explorers groups, a science-based programme for schoolchildren during the school holidays.

"By the second year we had 400 kids in each Explorers week and in the third year we had a queue right around the museum; there were 1200 applicants for 400 places."

Science workshops were held for secondary school students but Discovery World was his "special project", the first interactive science centre in the country.

When Mr Darby joined Otago Museum in 1969, just over 44,000 people visited the museum each year, but when he left it in 1999 the number was more than 500,000. Mr Darby was invited to join the Otago Peninsula Trust soon after he started at Otago Museum and was the main driver behind the concept and logistics of opening the albatross colony to the public.

"I did the very first displays in a tiny hut up at Taiaroa Head and it suddenly made the Dunedin public aware of the wildlife treasure they had up there."

His work on yellow-eyed penguins began in 1979.

"Almost everyone who worked on penguins would have been familiar with the work of Lance Richdale, who studied albatross and yellow-eyeds on the Otago Peninsula from the 1940s to the mid 1950s, but it was when I was piggybacking my kids around the peninsula I noticed yellow-eyeds behaved quite differently to all other penguins."

Mr Darby undertook a study of the species in his own time, and walked the entire Otago Peninsula and down to the Catlins surveying penguin nest sites.

"No-one actually knew how many yellow-eyeds there were, where they were and even worse, their habitat was being destroyed and predation of chicks was a very serious problem."

Mr Darby appealed to the World Wildlife Fund to buy a farm on the Otago Peninsula that appeared to have the most penguin nests.

Eighty hectares of it became the first yellow-eyed penguin conservation zone in the world.

In 1986, Mr Darby was invited to present a paper (while on sabbatical leave from the museum) to the British Seabird Group at Oxford University in the UK and he took what he knew would be a last opportunity to find his family.

He tracked his mother to an old people’s home in the north of England. She was 84 and he was 50.

Members of his mother’s extended family visited Mr Darby in New Zealand last year. Despite sometimes experiencing post-polio syndrome, Mr Darby shows no signs of slowing down.

With reports of last year’s breeding grebes literally queueing up to lay their eggs on the artificial nests at the marina, no doubt the birds are hoping those nests keep on coming.