The first part of the former Cadbury factory has only just been demolished, but the new hospital project’s programme director Mike Barns’ considerations are well ahead of progress so far.

"I have a wallchart in my head and in that I am already thinking halfway through the construction of the surgical building," he said.

Mr Barns, an architect, has spent the past decade building hospitals in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, complex builds much larger than the one he is supervising now.

Having decided it was time to come home, Mr Barns accepted the new Dunedin Hospital job, arriving in the city one day before Alert Level 4 went into effect.

Despite the enforced interruption, work continued on the project and its detailed business case — due in March — should be sent to Cabinet for approval in the next few weeks.

"The ministry and the district health board set the guidelines. We are essentially working with them to produce the hospital that they require for the people of Dunedin."

Another year of demolition and design work awaits before building consents are sought and tendering for building work begins.

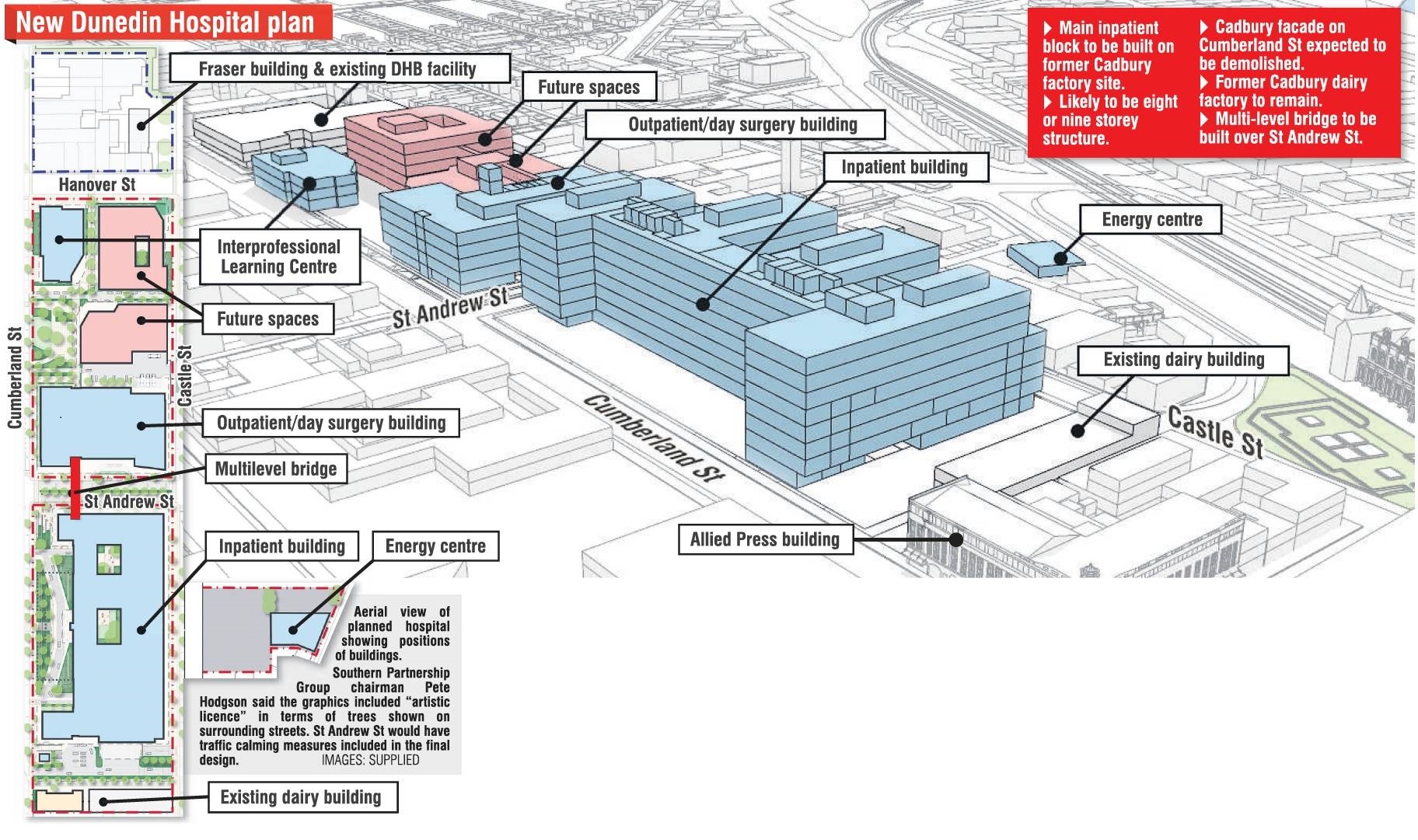

Two hospital buildings, built to national hospital design standards and conforming with Dunedin City Council regulations, would be the work of hundreds of on-site staff and backroom people, Mr Barns said.

"A very high design standard is required because it has to operate 24/7 and it is about saving lives, so the demands on consultants are very high."

There were several international design standards for hospitals, including one for Australia and New Zealand, so there was a template which set out how facilities should be designed and built to meet best practice needs, Mr Barns said.

Those templates, which demand a hospital with a minimum 45-year lifespan, then needed to be adapted to each unique location.

In Dunedin’s case that included taking into account its central city location, the busy roads either side, and the historic Dunedin Railway Station and the tourists who flock there.

"It has to be appropriate for the city; it can’t just be a spaceship that has landed from somewhere else," Mr Barns said.

"We are having benchmark studies of similar facilities from around the world, some of them in historic precincts, some of them in greenfields sites, so that the facility that is provided for the people of Dunedin meets local needs but is also of international pertinence in terms of functionality and the quality of design."

Mr Barns is expected to complete the hospital on time and within its $1.2billion-$1.4billion budget.

"All public works programmes are a challenge, and hospitals are another challenge on top of that because they are very complex buildings," he said.

"Another complexity on top of that is if you are building on reclaimed land and all the foundation issues around that; we have captured as much of those as we can into the project budget, so we have contingency for things we don’t know about that might be there.

"Having said that, we don’t have an infinite amount of money and we will have to manage the project price quite carefully."

Christchurch, which had replaced several hospital buildings following the Canterbury earthquakes and experienced budget and timeline blowouts in the process, offered an example for Dunedin to learn from, Mr Barns said.

Also to be managed is the issue which has led to delays in Dunedin: the tension between planners’ requirements and what clinicians needed to do their jobs.

Arguments over floorspace in the new hospital and an attempt to scale the project back from two buildings to one have delayed the finalisation of the project’s detailed business case, an essential component of the planning process.

"I think the frustration of last year is pretty much in the past," Mr Barns said.

"There are demands for clinical services which the DHB must meet, there is a consenting timeline with statutory timeframes we have got to meet, there are design and construction timelines which we have to meet, so the programme that we come up with has to address all those items and deliver the project on time."