Mounting studies drawing a clear link between cold weather and the spread of Covid-19 show why New Zealand must go all-out to eliminate the virus now, researchers say.

Epidemiologists had early suspicions that Covid-19 could be influenced by weather, given that other coronaviruses – notably the common cold – had well-established correlations.

Dr Felicia Low, a research fellow at University of Auckland-based think tank Koi Tū: the Centre for Informed Futures, has been reviewing a fast-growing number of papers looking at the link.

"We've seen some early indications that there are correlations between the rate of viral transmission, versus temperature and weather in general," she said.

"I've taken a closer look and there are certainly more papers – mostly from China – coming to the same conclusions."

One early pre-print study, by researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong, analysed more than 24,000 cases to find that temperature could cause a "significant" change in Covid-19 transmission.

"It is suggested that countries and regions with a lower temperature in the world adopt the strictest control measures to prevent future reversal," they reported.

In a more recent study, Finnish and Spanish researchers built an ensemble model to project monthly variations in climate suitability for Covid-19's spread.

That suggested that temperate warm and cold climates were more favourable to spread, whereas arid and tropical climates were less conducive.

A further US study, which drew on local temperature data and 166,686 cases in 134 countries between January and mid-March, similarly warned of a potential winter spike in Southern Hemisphere nations.

That study projected that, between March and July, Covid-19 transmission could fall by 43 per cent on average for Northern Hemisphere countries – but rise by 71 per cent, on average, for those on the other side of the equator.

"We can't yet tell whether we are looking at correlation or causation, and obviously there are many other confounding factors, like human behaviours," said Low, who has previously produced critical reviews on developmental origins of health and disease.

"But it's definitely important to keep an eye on this area because there are obviously implications for New Zealand as we get closer to winter."

Low said the seasonal influence could prove particularly important as Kiwis came out of lockdown.

"But the difference we have with a pandemic virus is there is no existing immunity in the population."

A lack of immunity also meant that the basic reproductive number of the virus – or the average number of people it spread to from an infected person – tended to be much higher.

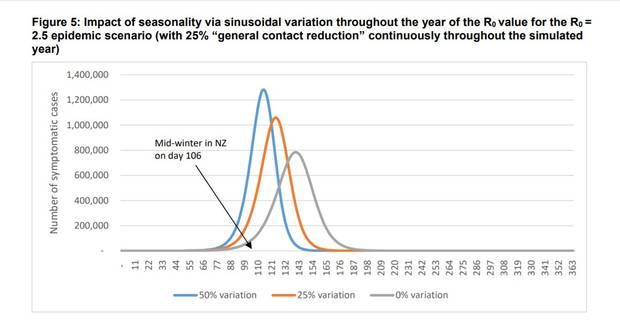

Modelling by his colleagues which accounted for seasonal impacts showed that, if the virus spread with a reproductive number of 2.5, a peak could be expected around mid-winter.

Baker said different pandemics had come with different seasonal influences.

"The 1918 epidemic, for example, was most destructive in November in spring, but in many countries it charged ahead regardless of the season."

He said there was still much uncertainty around the reasons for seasonality.

"In some countries, respiratory viruses just completely vanish over summer.

"Influenza is also highly seasonal, but then not all viruses are."

One was the direct effect of different temperatures and levels of humidity on the virus.

"The other is human behaviour, and that we just tend to spend a lot more time in close proximity with each other. In other words, we have physical distancing in summer and physical closeness in winter."

Whatever the case, Baker expected Covid-19 would prove a much bigger challenge for New Zealand in winter – which reinforced the country's efforts to pursue a strategy of all-out elimination while it could.

"It pays to remember that, over winter, we'll be seeing other respiratory viruses pop up that is going to make symptomatic diagnosis of Covid-19 very difficult.

"You'd have to be doing a lot more testing, with influenza, and everything else thrown in the mix."