The email arrived unannounced. From a professor too afraid for their career to use their work email. But sufficiently concerned about what is happening at the University of Otago to risk making contact.

The message was a follow-up from a phone conversation earlier in the day. A conversation they had gone home to have because they no longer trusted the privacy of university phones.

"I should have said, another consequence ... is hasty and damaging decision-making," the email stated, giving details that, if repeated, risk identifying the writer.

"This sort of behaviour puts departments at real risk," they concluded.

"Thanks very much for your time today. I really hope that across your interviews you’ve found enough material for the ODT to be prepared to take this on. The University is a central part of this town, and it really has gone rotten."

That is just one email, one phone call.

In recent weeks, the Otago Daily Times has heard from a score of people — most (but not exclusively) scattered throughout the university, many of them in senior academic roles — expressing serious concern, anger and sorrow.

"The whole university has become much less cohesive, more dislocated", "A lot of good people have been gotten rid of, and others have left in disgust", "There is a crisis of morale at the University of Otago", "Something has gone radically wrong and changes need to be made".

That is one perspective.

"Last year, we topped all of the major highly competitive research funding pools, earning the highest level of research income in our history," she said.

Students were doing well and academics elsewhere were keen to work at Otago, she said.

"On the whole, our culture here is good," she said, allowing that there is always room for improvement.

Indeed, New Zealand’s first university is ranked in the top 20% of universities worldwide, based on an international reputation for excellence.

However, it is no secret that the University of Otago has been undergoing change in recent years.

Some subjects and courses have been cancelled or threatened with closure. Some departments have been restructured into schools and programmes with a more removed layer of management and the prospect of being easily disassembled in the future.

Wholesale change has come with the Support Services Review (SSR). Still only partially implemented, the university-wide SSR restructure has centralised non-academic, general support staff, breaking up long-standing academic-general staff teams in the name of flexibility, efficiency and cost-saving. The new support services structure has come with its own layers of management.

Restructuring is always disruptive and upsetting. But, say some of those who have spoken to The Weekend Mix, the change at the university goes beyond what they describe as the appalling implementation of a partially justifiable restructuring. They say a significant and negative culture change, led from the top, is undermining the whole ethos of the university.

"Universities in New Zealand are supposed to be the critic and conscience of society. But I’m not confident we can even be the critic and conscience of ourselves," one professor said, echoing the words of others.

Dissent moved into the public arena late last year, when Prof Kevin Clements and Emeritus Prof Peter Matheson wrote an opinion piece expressing their concerns, published in the Otago Daily Times. The piece praised the university’s cutting-edge research, innovative teaching and billion-dollar contribution to the Dunedin economy. It also pointed to what the writers believed was a "toxic" climate in which academic and general staff felt betrayed and disheartened by the actions of top management. The university was "very sick" and "radical action" was needed, they wrote.

Prof Clements, who was down to 20% of full-time, has since resigned.

No-one spoken to by The Weekend Mix about the university, whether employed there or not, wanted their names attached to their comments. But comment, they did, by-and-large.

Among them are nine professors from disciplines across the spectrum, as well as other academics and general staff. A dozen of those who have spoken are employed by the University of Otago, some are former staff and some are speaking from outside the campus but have close connections to it. Most of the academics who have commented are in positions of responsibility, having built successful careers and had their accomplishments trumpeted by the university.

The only person speaking on the record, apart from university senior management responding to concerns, is the Tertiary Education Union’s Otago organiser Kris Smith.

What those unnamed individuals are collectively describing is a university they believe has, during the past three years, gone from a place of devolved responsibility, high trust, collegiality and strong goodwill to centralised control, fractured communication, curtailed freedoms, low morale and high stress.

The centralisation of control has been marked, they say.

Layers of bureaucracy have been added. Power has been vested in people more distant from the coal face of researching and educating.

"There is an increasing culture of micromanagement and control," someone else says.

"There is resentment of the top-down management style of the current university leadership," adds another.

At the same time, there is a perceived widening chasm between the clocktower registry, where senior management are located, and the rest of the university.

"We don’t know what we’re doing. We don’t know what the plan is. We don’t know how we’re contributing. We don’t know whether the management is actually on our side," one says.

"I’m particularly troubled that senior management don’t seem to get it; that they’ve made a series of choices, some of which didn’t work very well. They’ve been told that by people, but they either wilfully or unconsciously cannot believe it," says another.

The university’s senior management consists of the vice-chancellor (V-C), chief financial and operating officers, a director of human resources (HR), two other directors, three deputy vice-chancellors and four pro-vice chancellors. Prof Hayne has been vice-chancellor since 2011.

The governing body of the university is the University Council, which consists of 12 appointed and elected members, and is headed by the chancellor. Dr Royden Somerville QC is the chancellor. Prof Hayne is also a member of the council.

There is a feeling, say those who spoke to The Weekend Mix, that dissent is no longer tolerated at the university.

Some staff believe they cannot safely express critical views on work emails, university-hosted websites or university phones.

"There’s a climate of suppression of views and information, and fear of repercussions," a professor says.

"Academic freedom no longer exists in this university ... We are circumscribed in what we teach, research and say," another says.

A number of those who commented on concerns, emphasised that they believed they were risking their careers by speaking up, if they were identified. They said they were speaking out of concern for an institution they had felt a lot of loyalty towards, but that goodwill was being quickly eroded.

"There used to be a social contract between academics and the university. The job requires long hours and quite a bit of stress because you have a lot of responsibility. But we would be trusted to get on with it. In return there was a certain amount of job security and a culture of mutual respect," one person said.

"But that social contract has been well and truly destroyed.

"I’m prioritising my students ... but I’ll be damned if I’m going to spend my evenings and my weekends doing other parts of my job. Given what is going on here, you have to grow other parts of your life in order to survive."

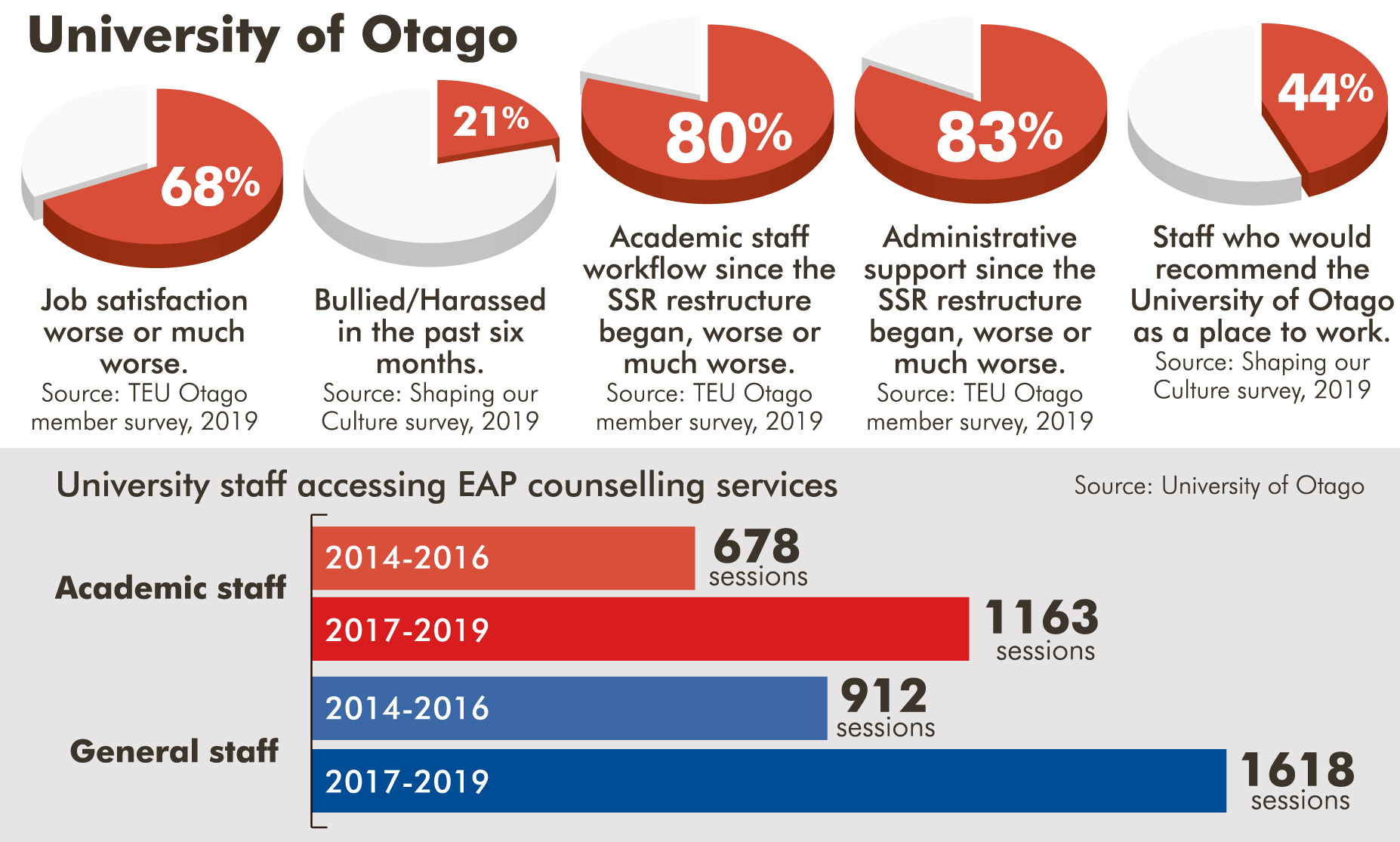

A survey conducted last year shows most academic staff feel their job satisfaction has declined. The confidential Tertiary Education Union-member survey, given to The Weekend Mix by a university staff member, shows 48% of survey participants felt job satisfaction was worse and 20% felt it was much worse.

In the same survey, 80% of academic staff say their workflow has got worse or much worse since the SSR restructure began.

Tellingly, in a survey the university itself conducted last year, which received more than 2000 responses from staff, only 44% of respondents said they would recommend the university as a place to work.

Two professors say they believe the result would have been close to 100% if the survey had been conducted several years ago.

"Every time I think about that result, I want to cry," one of them says.

Previously, trust was a keystone value at the university. Academics were given a lot of rope. And most often it worked, because they were self-motivated people.

Centralised control and micro-management has been de-motivating and has largely destroyed trust between senior management and many academics, they say.

"There is no longer any trust with the management," one person says.

"The lack of trust is such that you have to get a sign-off for everything," another professor adds.

Several of those spoken to say the shared sense of purpose across disciplines has been severely damaged.

"Trust and collegiality have been thoroughly challenged," one person says.

"We may not have been a very efficient organisation, but we relied on each other very strongly. We were an organisation that valued people," a distraught professor says.

"Strength of teams and sense of shared purpose has been diminished," another says.

One professor says, despite all that is going on, peer-to-peer relationships within their discipline are still strong. Another says one positive is that students have, in the main, been shielded from what is going on.

A third person says not all areas of the university have been detrimentally affected to the same degree. All three, however, and everyone else who spoke on condition of anonymity, say morale among staff in most corners of the university has tanked.

Low morale at the university is "very, very widespread", says someone outside the university, whose position of responsibility brings them into regular contact with staff.

Exacerbating the situation, that person says, is "the struggle of the university to acknowledge the strain staff are under, and the expectation people will just celebrate what is happening".

That echoes a professor who says "We just spent a year focusing on our 150th rather than dealing with the fact that we had a large scale, poorly planned change that negatively impacted a lot of people. We had a celebration saying how good it is and not addressing the elephant in the room".

Mental health and wellbeing appear to have been a casualty. The university survey that highlighted low numbers who felt the university was a good workplace also revealed that 40% of university staff felt their health and wellbeing had suffered because of work. Among those, stress and anxiety was most commonly mentioned.

In response to a request for information, the university provided figures on the number of university staff accessing Employment Assistance Programme (EAP) counselling services. In the three years to the end of 2016, staff used EAP services 1590 times. During the past three years, that jumped to 2781 counselling sessions.

"Talk to any psychologist in town and they’ll tell you about University of Otago staff over the past two or three years," one professor says.

"I’m not sure I would use the EAP because I’m not sure it’s not being monitored," says another professor who adds that they are stressed but knows of others who are "much worse; they’re at breaking point".

Another person says they have been told on good authority that for the past couple of years general practice doctors in Dunedin have been noting increasing stress levels and requests for medication from university staff.

One person says it is not just staff opposed to the new university culture who are struggling to cope.

"Senior staff who have bought into the changes are now getting stressed by the long hours they are having to work and are making ill-considered decisions, made in a panic, and are being nasty to those they have authority over."

A number of people mentioned a bullying culture that they believe emanates from senior university leadership. The university survey mentioned above also shows that 21% of staff stated they had experienced bullying and/or harassment in the past six months. According to WorkSafeNZ, that is at the high end of the average range for a New Zealand workplace.

One perceived consequence is high staff turnover.

"People no longer feel loyalty to the university," one person says.

"Once you think your voice doesn’t count in any way and decisions are made and people go, you really feel you are losing a big part of it," another says.

"I look at job offers far more carefully now," a long-standing Otago professor adds.

Figures requested by The Weekend Mix show during the past three years, 281 academic staff have resigned and 51 have retired. That is one fifth of the total number of academic staff, and a little higher than the national average workplace turnover rate. In addition, general staff have been centralised, no longer reporting to academic heads of departments but to shared services management who allocate staff across the university as needed.

"Losing institutional knowledge and loyalty are the two biggest things for any institution," says a professor, one of several people to mention the negative impact of that loss.

Ross Pearce is a change manager; he’s chapter lead for the Auckland chapter of the Change Management Institute.

Any change is difficult for people, who tend to react to disruption with fear, he says. But significant change without widespread dissatisfaction is possible.

Told the enterprise at issue was a large Otago organisation that had undergone significant change resulting in staff concerns about centralised control, low morale, loss of job satisfaction and high stress, he said you could reach the conclusion it hadn’t been managed as well as it could be.

To successfully make wholesale change requires "a significant amount of effort" by all the leaders in an organisation, including formal leaders and "key influencers".

"It’s really important for organisations to get those opinion leaders aligned on what the changes are. And, indeed, to engage people at an early stage on their ideas about how the change could be managed, rather than the change being done to people."

Last year, during its sesquicentennial, the university launched a culture-building project, Shaping our culture together, He waka kotuia. United Kingdom-based consultants April Strategy have been brought in to facilitate it.

Most of those interviewed for this story strongly question the value and integrity of the project.

"There is widespread feeling the consultation isn’t genuine," one says.

"I’m deeply cynical about it. It’s as though the problem is that we all need to be nicer to each other," another says.

"People I’ve spoken to have been incandescent with fury at the implication that it’ll all be fine as long as we’re all nice to each other ... That’s not in any sense looking at what is causing the problem," someone else adds.

Most of the blame is being directed towards senior management.

One person said they had seen examples of genuine care being expressed by top management. They then added that a lot of people were "struggling" and "disillusioned" with the changes the vice-chancellor had introduced in the name of efficiency.

"From that managerial, business-model point of view it’s a more streamlined machine. But it raises all the philosophical issues about the purpose of a university," they say.

"People are anti-HR, but they are easy targets who are doing what they are directed to. HR are not there for the staff; they are there to keep the V-C safe," another person says.

"Is this a situation where the entire [university] government needs to be swept away, so we get a new set of leadership we have confidence in?" a professor asks.

The Weekend Mix spoke to TEU Otago organiser Kris Smith, running through a list of the concerns expressed by those who had spoken anonymously to the newspaper.

Yes, says Ms Smith, members have raised all those concerns with the union.

"Any restructuring within an organisation is incredibly unsettling," Ms Smith says.

"The scale of the restructuring was pretty enormous and hasn’t been completed yet."

Ms Smith says the TEU has taken the concerns to the vice-chancellor and to HR director Kevin Seales.

"It was on the basis of us bringing together all those concerns that the employer agreed to have a group, with TEU representation on it, that reviews what has happened."

"We are now in the process of working through how that will operate. Terms of reference haven’t been set yet ... We are putting in place processes to work through the issues raised. The V-C and HR director are open to that."

The vice-chancellor responded to questions posed by The Weekend Mix about the Support Services Review and culture project globally

, saying her institution had experienced unprecedented success.

It had topped all of the major research funding pools, earning the highest level of research income in its history.

"The calibre of our teaching is outstanding, with a marked increase in student ratings of the effectiveness of our teachers. We continue to attract outstanding academic and professional staff from across New Zealand and overseas. Our communications team alone would be the envy of any newsroom in New Zealand.

"For the first time in the history of the University, we have promoted more women than men to the rank of Professor. On the basis of national data collected by the TEC [Tertiary Education Commission], our students are the most successful in New Zealand. This year we will, once again, welcome record numbers of Maori and Pacific students to Otago. Student satisfaction with Otago is extremely high. Our Dunedin campus continues to be rated as one of the most beautiful in the world.

Not one of these things happened by accident. It is because the University has strategically planned and made sure we had the right people and resources to make sure we delivered in these crucial areas.

"Our EAP programme is a clear indicator of our commitment to being a good employer. It is not an indicator that we are a poor employer. This service is not restricted to work-related issues. In fact, 65% of the services that staff accessed last year were for non-work-related personal issues. We support this service at our own cost because we want people to be happy in all aspects of their lives. The University also increased the number of sessions that staff could access for any reason from three to six in 2017. Once again, this was part of our commitment to help staff through challenging times in their lives, be it personal (65%), or work-related.

"We employ 11,000 people, and there will always be a small number of staff who struggle with change. But the reality was that the University could not have stayed the same. Our funding environment would not allow us to continue as we were. This was simply not an option and we would have found ourselves becoming a much smaller and less capable organisation. Instead, we need to be nimble, innovate and able to not just operate, but thrive in the modern world with all of its opportunities and challenges. We have faced many challenges over the previous year, and under the old structure I do not think we would have been able to cope with the unprecedented events we experienced, including the March 15 massacre in Christchurch, the Unicol fire and the tragedy that took Sophia Crestani’s life last October. I strongly believe that we would not have been able to respond as effectively to the Covid-19 epidemic under the previous structure.

"We are confident that the SSR will meet its intended aims, which will set us up for the future. There are many happy people working at the university and I see them as a very important part of our future. We provide superior terms and conditions to our staff, including competitive salaries, generous sick leave, holiday time, and parental leave. As with any large organisation, there are issues to work through. We are privileged to have established a strong relationship with our union and we are working with them on individual issues.

"On the whole, our culture here is good, and of course there’s always room for improvement. Most staff, through the culture project, made it clear to us that they wanted less complaining, gossip and negativity and they wanted more respect, collaboration, kindness and support. This is where we are heading, and we are hoping to take as many people with us as possible. I would challenge all workplaces, including the Otago Daily Times, to take a brave look at their own culture and seek to improve."

"She is disappointed that some staff continue to find the changes challenging, but she is equally encouraged by the large number of staff that she works with every day who are thriving in the current environment. At the same time, the satisfaction and the success of the current students at Otago is another clear sign that things are moving in the right direction."

Asked how the university knew the purpose of confidential staff counselling sessions, the same email states "providers give general non-personalised reasons for use of the service".

Late in the piece, an email arrived from an overseas academic who spent time at the University of Otago during the past 18 months. They asked to remain anonymous.

"Being a visiting scholar at many institutions worldwide, I am well used to witnessing the pernicious effects of poor management on staff as well as the converse — the difference it makes when good, steady, unobtrusive leadership is in place," they say.

"My immediate hosts during my stay at Otago University were outstandingly meticulous in their care and attention to detail.

"But what was immediately apparent upon my arrival was that this university and its centralised administration systems and culture of management was not working in the interests of either staff or students.

"It’s crystal clear that there is a major funding gap in the higher education system in Aotearoa New Zealand. But the answer is not to wage a war of attrition on staff, but to work collectively for structural change and clear government action.

"I spent time with staff who were locked in pain and anger at what their institution had become ... the impact on the health and wellbeing being of staff was clearly acute.

"All of this led to a sense of an institution that had quite simply lost the plotline for what it means to be a university.

"Universities can turn this around, can be places of flourishing and robust debate, and can do so quickly. It needs leadership that is not at war with its staff, and which sees scholarship as an ecology, welcoming criticism and conscience indeed, including conscientious objection."