The long, narrow lecture table was one he helped rescue from the University of Otago Medical School about 25 years ago.

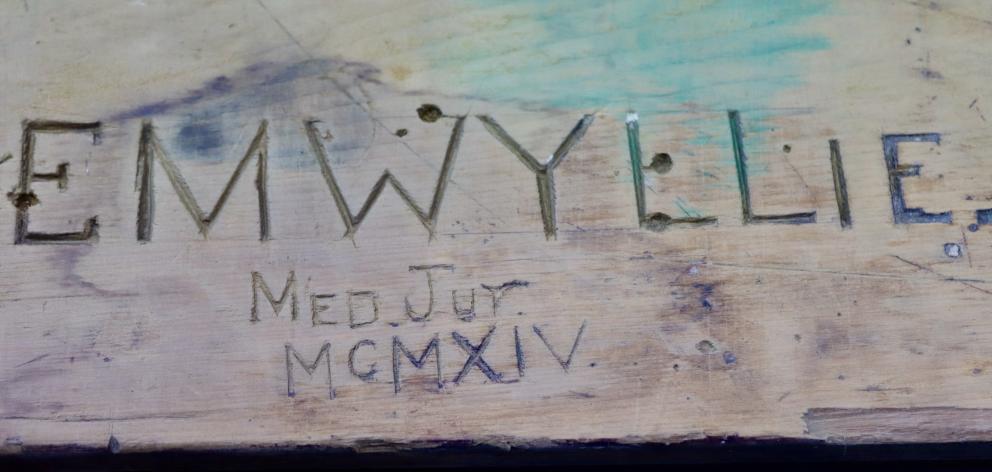

Grimy and covered in paint, the top of the old desk had the signs of young student graffiti.

As Mr Macdonald began stripping back and cleaning the bench, one name caught his eye.

Twenty-two-year-old University of Otago medical student Eric Melvyn Wyllie had scratched his name as well as the words ‘med jur’ and the date, 1914, in Roman numerals.

Mr Macdonald decided to search the name online and discovered a tale of bravery and service.

Due to the need for doctors for the war in Europe, Mr Wyllie’s final bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery examinations were brought forward from January 1915 to August 1914.

In April 1916 the newly minted doctor departed overseas with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

While constantly exposed to enemy fire his unit set up a car post — a mobile medical station — at Masnieres. The unit went even closer to enemy lines to establish a bearer relay post.

Capt Wyllie supervised the evacuation of wounded soldiers from these advanced Royal Artillery posts, all while under enemy fire.

For this act of bravery he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry on the field of action.

After the war, Dr Wyllie moved to Foxton in 1921 to become the local general practitioner.

He married Eileen Robinson in 1924 and the couple would have two boys and two girls.

The story, as conveyed in the New Zealand Truth newspaper, described how John Westlake, Mr and Mrs Wright and their four children, as well as their employee Samuel Thomson, were found in the humble ruins of a whare.

Dr Wyllie conducted the autopsy and was caught up in a mystery when in the remains of one of the men, Mr Thomson or Mr Wright, he found evidence of a gunshot wound.

Dr Wyllie believed the gunshot could not have been self-inflicted, but was it murder or a tragic accident?

Was owner Mr Westlake, who was known to have poor eyesight, the murderer?

The bodies of Mr Thomson and Mr Wright were found in the same room, so did one kill the other only to die by fire?

The coroner’s inquest proved murder, but failed to name the murderer.

Dr Wyllie was not to have a long life, dying in 1936 at only 43, when his oldest daughter was only 12.

Mr Macdonald hoped by sharing the story of Dr Wyllie, relatives might get in touch to share more details, such as why he died so young.

"I couldn’t find out what actually happened to him, because the obituary [just] reads ‘demise’."