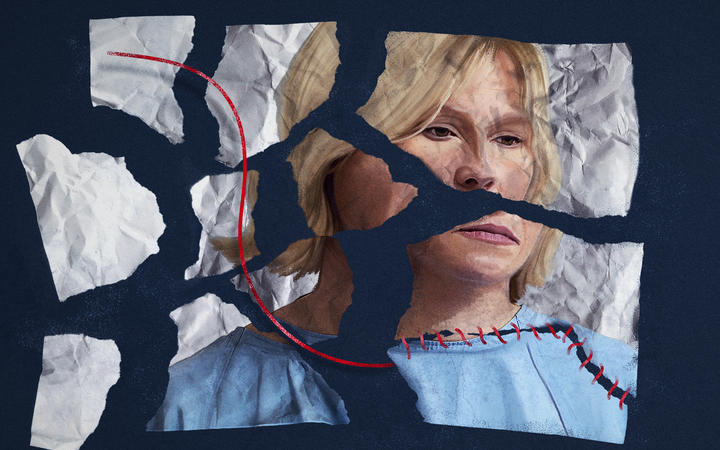

ACC has cut off a mother whose baby emerged from her rectum and vagina, as part of a review on which birth injuries the corporation will cover. Women say they're struggling to get treatment - and the number of women being injured giving birth is growing.

When Susan's midwife calls for urgent help, the on-duty obstetrician walks into the delivery suite, peers between Susan's legs and walks straight back out again.

She's never seen anything like this before: Part of Susan's baby is coming out of her rectum and another part out of her vagina.

Outside in the corridor, she pulls herself together and returns to Susan's room. It's too late for an emergency caesarean section but the doctor knows the baby needs to be born quickly. She pushes the baby back up the rectum and brings her back down the birth canal.

The 7lb5 baby enters the world unscathed but Susan's injuries are horrific. Her daughter tore through her vaginal wall, all her perineal and pelvic muscles and into her rectum.

"I thought I was going to die," Susan recalls of the searing pain.

A surgeon, who later performs seven operations to try and correct the damage, tells Susan it's the worst birth injury he's ever seen.

When she's sent home, her life is unrecognisable. "I couldn't drive for 12 weeks, I couldn't sit, I couldn't do anything. I had carers that came in and did housework because I couldn't do anything for a long time. I relied heavily on my family and friends because I was bedridden."

She's not only incontinent and in constant pain, her mental health is also affected. "I felt isolated a lot. I spent a lot of time at home because I was too scared to go out in case I had accidents. It's been really horrific."

Since the birth in 2016, Susan has had several operations, extensive pelvic physio and counselling to help her recover and process the traumatic birth. Nearly five years on she's still unable to work and needs more surgeries and physiotherapy to correct rectal prolapse, incontinence, constant pain and bleeding. But she's uncertain she'll get the medical care she needs.

After the birth, ACC accepted her claim and paid for the treatment and care she needed outside the public health system. But in July last year, she got a phone call: ACC was revoking her claim. "They said, 'Because your delivery didn't involve medical instruments… we can just no longer cover you'.

"I was told it should never have been accepted. I was pretty gobsmacked."

***

A month before Susan got that phone call from ACC, the corporation had reviewed its policy on perineal tears. For years it had covered birth injuries, but in June the organisation looked at its rules following "inconsistencies" in the number of claims being made between DHBs.

ACC's chief clinical officer Dr John Robson says the aim was to "improve clarity over our cover" and was carried out by obstetricians, academics and midwives. It concludes ACC can only apply what the ACC Act allows. "ACC can cover perineal tears that are the result of treatment, or the failure to provide treatment (a treatment injury).

However, most perineal tears are not caused by treatment but by the birthing process and would be addressed in the normal course of care provided by the health system."

A successful ACC claim means a woman can get physiotherapy or even surgery in the private sector. Home help or wage support might also be offered and a dedicated case manager oversees their recovery.

Treatment though the public health system provides surgery and physiotherapy but the waiting times can be long and there's no home help or wage subsidies.

Before the review, perineal tears topped ACC's list of the 10 most common childbirth-related injuries for women, with around 30 claims being accepted each month. But since August, fewer than four claims have been successful each month. The true number of claims is unknown as ACC won't reveal figures fewer than four due to privacy reasons.

While ACC cover has fallen, the number of women suffering from severe tears is increasing.

Susan's birth injury was extremely rare, but 85 percent of women will experience some kind of obstetrical tearing during childbirth. Mild tears - those classed as first and second degree - though painful, usually heal with minimal medical treatment within months, if not weeks. But the more severe kinds - third and fourth degree tears - are often extensive injuries involving damage to muscles and tissues in and around the anus, rectum and pelvic floor - and more women are sustaining these.

Severe tears in low risk pregnancies have increased by 1.1 percent to 4.5 percent in the 10 years to 2018, Ministry of Health figures show. During the same period, the rate of women giving birth without any injury to their genitalia has fallen from 35 percent in 2009 to 27 percent in 2018 (More recent data is not publicly available until next year).

Severe tears often require repairs under general anaesthetic and ongoing pelvic physiotherapy to help with issues such as prolapse, incontinence and pelvic pain.

***

The more medical intervention there is in a birth, such as induction or the use of forceps, the more likely there will be complications, such as tearing - and internationally, medical interventions are rising, Wise says.

"We're also seeing women slightly older at the time of their first baby being born, women are slightly more overweight. Women are having slightly larger babies."

Pregnancies are also becoming more complex, with conditions like pre-eclampsia, high blood pressure and problems with diabetes in pregnancy now more common, which are all associated with complications during labour and birth. More doctors and midwives are now also trained to recognise tears so more are being reported, she says.

No matter the cause, the impact on new mothers can be profound, as some tears can take months, or even years, to heal, Wise says. "Physically, with pain, I think that it's quite draining. It can affect their quality of life, it can affect their social life, sexual relationships, exercising. It can cause people to be quite anxious and uncertain, feeling quite low and having a change in perception of themselves. That can certainly affect relationships, both with the baby and with partners."

Wise believes ACC's stance on severe tears is "too restrictive" because the international research on what causes them is inconclusive. "Every time I read a new study about this topic, it seems to add a bit more to the controversy, and there is no definitive answer yet. So I think to me, I feel like the new [ACC] guidance is a bit too restrictive, and doesn't take into account the morbidity, the flow on-effects and complications of having these significant tears for women."

ACC's clarification is also putting added strain on the public health system, which is already struggling to cope, she says.

"We would routinely put in the paperwork to ACC, and now it's getting declined more and more often. The flow-on effect of that is that more of these women need to be seen in our public health care services.

"I just saw somebody last week who had sustained childbirth tear about 10 months prior and I felt terrible that this woman had not yet been able to see a physiotherapist or a specialist and it has had ongoing significant impact on her physical and mental health."

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends women with severe tears are seen by a specialist within six to eight weeks and are also seen by a pelvic physiotherapist.

"That can actually improve a lot of the symptoms. So that's a really important piece of the longer term management of these tears," Wise says.

But a study Wise published last year, looking at how seven hospitals cared for women with severe tears between 2005 and 2014, found many were unable to see a specialist within the recommended time frame.

"We found a lot of variability with some hospitals only being able to see about half their women within six or eight weeks, while others up to about 80 percent."

That leaves a group of women not able to access either a specialist or a physiotherapist at their DHB in a timely manner, Wise says, and that's a "big problem".

For a mother reliant on DHB-funded pelvic physiotherapy, the wait can be long. If you're in Taranaki, you'll wait on average 522 days compared to just 14 days in Auckland for urgent cases. Women in the Eastern Bay of Plenty have had no access at all to pelvic physio until this month when one was finally hired.

Most women in other parts of the country are waiting anywhere between one to six months to get an appointment.

Wise says there needs to be better access to care for these women. "The Ministry of Health really needs to think more about how to better support women who have just had a baby, because it's a really difficult time at the best of times and to have had one of these severe tears, I think that's exactly where we need to be putting our resources, into that exact time for women."

Danielle, 28, knows all about waiting. A forceps birth left her with a third-degree tear and vaginal and rectal muscles so weakened that she sometimes leaks faeces. Still, due to Covid-19, she waited a year to see a gynaecologist at her DHB.

That doctor filed an ACC claim for the birth injury, but Danielle's been waiting four months and still hasn't heard whether it's been accepted. "Technically I should qualify because I had forceps delivery with no episiotomy. But each time I've called them they say they're waiting on information from the doctors still."

She feels her recovery is in limbo while she waits for her claim to be processed. "I'm a little bit tired of waiting… I don't want to have incontinence for the rest of my life."

She feels women in her situation are being treated unfairly by ACC and the health system. "My husband had a couple of motorbike accidents and he was off work for a couple years and had surgery and physio and chiropractor. I mean I love my husband dearly, but he can go and choose to ride a motorbike and hurt himself. I guess I choose to birth but I don't choose the outcome of my birth, and then you're not covered at all. And it's also just the waiting."

While she waits, Danielle is considering making an appointment to see a pelvic physiotherapist privately in the hope of accelerating her recovery.

***

Rachel is also having to seek private medical care after her doctors told her it wasn't even worth filing a claim with ACC.

Seven years ago, Rachael was discharged from hospital within hours of giving birth to her son, despite sustaining a third degree tear following an episiotomy. It took her months to recover and her DHB offered no help. It was only in 2019, when she started experiencing issues, that she saw a private gynaecologist. The doctor told her the problems were due to the birth injury she suffered seven years earlier.

"I had about 30-something stitches and a third degree tear. They stitched me up, but they only essentially stitched up the surface wounds. They didn't stitch up any of the muscles and the ligaments that they cut through to get to him," she says.

But it wasn't worth filing a claim with ACC, her doctor told her, especially as Rachel had medical insurance. "Literally her words were, 'you definitely would be eligible for an ACC claim. But it takes so long for them to process it, and nine times out of 10, they don't accept it, they make it extremely hard for women to get this kind of coverage'."

***

"I think it's appalling. Why are they [women] having to find money themselves to be able to get the help, the surgery, the physiotherapy or whatever it is they're needing… Why are they having to fork out for that," Sargent says.

Sargent, a former midwife who now provides birth trauma talk therapy, can't believe how few ACC claims for severe tears are now being accepted and says the lack of access only increases the trauma that many women have suffered. "It's the ongoing physical pain and difficulties around sex, around urinary incontinence or faecal incontinence… these tears are having major, major fallout for women."

She wonders if more would be done if men were having a hard time getting genital injuries fixed. "I feel like it's part of a wider sort of patriarchal discourse that underpins our lack of regard for women's health issues generally."

***

ACC's John Robson acknowledges there are some women who face "severe and life-changing physical and mental challenges as a result of perineal tear", whether or not they are eligible for ACC cover.

"We don't wish to diminish their experience. We understand and appreciate they have severe, lifelong complications."

But just because they're not covered by ACC doesn't mean they're not being treated, he says. That's because ACC provides annual bulk funding to DHBs, known as Public Health Acute Services Funding, which pays for the acute treatment of injuries within the hospital setting. Further patients are able to access treatment through the public health system for the management of conditions which are not covered by ACC.

Over the past two years only 4 percent of the total cost of accepted claims for perineal tears have involved entitlement payments, such as wage support and compensation, which shows the vast majority of claim costs go towards treatments such as surgeries and private pelvic physio, Robson says.

The clarification of what ACC will cover when it comes to perineal tears was done in consultation with experts in the sector, including obstetricians, academics and midwives. It "provides certainty" for treatment providers, he argues.

ACC Minister Carmel Sepuloni is also providing certainty about one thing: "We are committed to examining the range of conditions ACC covers and I'm quite determined to make sure that birth injuries are part of that consideration.

"First and foremost, I absolutely do empathise with the women that are in this position and have this experience."

But her certainty falls away when it comes to how quickly changes could be made.

She does, however, guarantee it will be looked at this term. "I'll certainly be seeking advice from ACC on what can be done."

She says ACC tells her only two women with severe tears have had their successful claims revoked since 2005. "It has been, I can imagine, very difficult to have that support cut off."

Sepuloni is now seeking advice on how and why this might happen to some claims.

Susan is one of those women. She has now been fighting ACC, trying to get her cover back, for nine months. She's resigned to the fact it could be a "long fight".

"You know... I didn't ask for any of this. I keep having to have psychiatric assessments and prove myself again with specialist after specialist."

Her hospital file detailing her injuries and all her treatments is huge, she says, and she wonders what more information ACC needs. She feels completely let down by the organisation and the health system, but there is a glimmer of hope. After being made aware of her case by RNZ, Sepuloni has asked ACC to review its decision with fresh eyes.

"We do want to make sure that all those who access the support of ACC have their dignity upheld, that the decision making is precise and that people can be assured of that," Sepuloni says.

That's all Susan wants too.

"Women need to have that support, [to] feel like they can have the time off to heal, and get well."

That phone call last July ended her weekly salary compensation and ACC-funded treatments. Her monthly private pelvic physio appointments alone were costing ACC $180 a pop.

"To see my colorectal surgeon privately is $300-plus for just a consultation... and I've actually been declined a couple of times to even be seen on the public list.

"It's taken a lot of fighting on my behalf to get the things I need."