On screens big and small, vampires are increasingly becoming less demonic and more sympathetic, less evil and more nuanced - and have become the most eligible bachelors around.

In recent years, the shift has become especially pronounced.

Prime's new show True Blood takes these caped corpses further still towards social respectability, as Oscar winner Anna Paquin plays a young woman who falls for a 150-year-old Civil War veteran played by British Shakespearean actor Stephen Moyer.

These days, modern, morally brooding vampires abound.

Stephenie Meyer, author of the Twilight saga, about a 17-year-old girl who falls in love with a sexy young vampire, was recently called the "new J.K. Rowling" in Time.

Will Smith's I Am Legend grossed $US250 million at the box office.

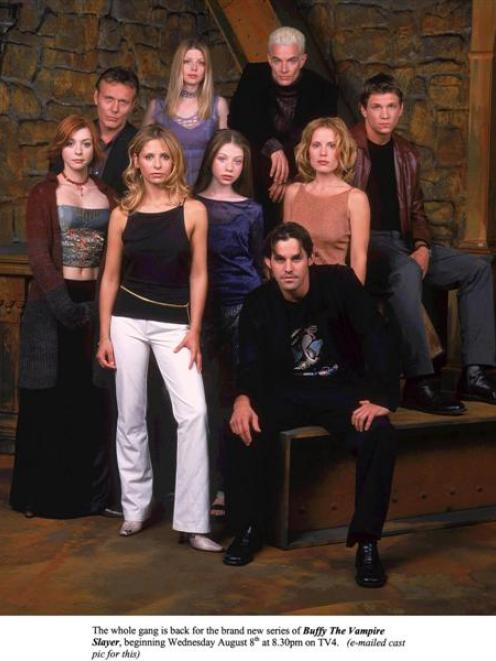

And before that, TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer ran for seven seasons through 2003; its spin-off, Angel - about a vampire whom Buffy fell in love with - ran for five.

With heart-throbs like that, it's easy to see why humans keep falling in love with the toothy Lotharios.

Vampires in pop culture have come a long way from their 19th-century roots in penny dreadfuls and countless film versions of Bram Stoker's Dracula.

They were demons, sex fiends in a deep Freudian sense, rebelling against Victorian repression in ways that gentlemen never could.

They hissed at crucifixes and seduced women and men from righteousness into evil.

But they started gaining moral complexity, especially with Richard Matheson's 1954 last-man-on-Earth novella, I Am Legend, about a lonely human in a vampire-overrun world who lives only to kill his undead neighbours, until he realise he and they are not that different.

Matheson introduced the notion of vampire multiculturalism, explaining that while the undead who lived as Christians fear The Bible, those who lived as Jews are repelled by The Torah.

The Will Smith film version changed crucial plot elements in the climax, but one thing remained the same: The line between vampires and humans was getting blurrier.

In 1992, two very different takes on the legends appeared on-screen: Bram Stoker's Dracula, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, an otherwise middling teen vampire comedy that unexpectedly led to a fantastic TV show.

Coppola's Dracula made a concession to modernity by going outside Stoker's text to write a back story for Dracula's moral bankruptcy.

In Coppola's telling, the count became so overwhelmed with grief at the death of his one true love that he damned his soul to perdition and fell into madness and blood lust.

But the film sagged under the weight of its ambition to be true to the text and to the changing conception of vampires, and the villainous bloodsucker was too one-dimensional to be satisfying.

Neil Jordan more successfully explored these themes of love and loss of humanity from a vampire's point of view in his lavish, moody 1994 film rendering of Anne Rice's hugely popular Interview With the Vampire, which contrasted Tom Cruise's pitiless Lestat with Brad Pitt's more humane Louis, the titular interviewee.

But Buffy was the way of the future.

The TV show introduced her boyfriend, Angel, one of the most sympathetic vampires of his day.

Unlike Dracula or Lestat, Angel slept through the day in an apartment, not a coffin, and drank animal blood so as not to feed on humans.

He fought evil vampires and muddled through romantic love with a teenager, as though he were alive, pimpled and 200 years younger.

Wesley Snipes' Blade, based on a comic book superhero, came to the screen in 1998, and he was even further from the classic vampire.

A half-breed who could walk in daylight, Blade injected a synthetic-blood serum to slake his thirst and killed vampires to assuage his moral guilt for having once fed on humans.

As in True Blood, his drink helped restore his humanity.

Vampires were transforming from oversexed Satanic demons into regular anti-heroes, imperfect and inhuman but worth rooting for anyway.

And their authors see them that way.

True Blood creator Alan Ball says: "Vampires are just like humans.

Nobody's 100% good, nobody's 100% bad."

Meyer agrees, saying that all her vampires have the moral freedom to choose.

So does novelist Amelia Atwater-Rhodes, who explains, "Bad guys who are evil for the sake of evil are boring."

(Atwater-Rhodes once created a vampire named Alex Remington.

No relation.) True Blood has a noble macabre pedigree.

Ball's previous show was the acclaimed Six Feet Under, about a family of morticians, and the show is based on a series by murder-mystery novelist Charlaine Harris.

True Blood vampire Bill Compton maintains there's nothing demonic about vampires, who, he says, "can stand before a cross, or a Bible, or in a church, just as readily as any other creature of God".

He just wants to rejoin human society.

He drinks synthetic O-negative, romances a human girl and defends himself against vampires who disagree with his desire to mainstream.

The show satirises the debate between mainstream and isolationist vampires as standard identity politics, with a vampire lobby group (the American Vampire League) facing off against a bigoted anti-vampire TV preacher whose wife looks like Tammy Faye Bakker.

The townspeople aren't too sure what to make of the undead in their midst either, particularly when the immortals start catching the eyes of attractive women.

As one character grumbles: "You know what I really wish would come to Marthaville? Buffy or Blade."

It's said wistfully.

Vampires are out of the coffin, and they're not going back in.

No matter how mundane their politics or morals, vampires will always be cool, because sex and death never go out of style.

More and more, vampires are not hard to sympathise with: They eternally have to choose between loving us and feeding on us.

Given that rapacious dilemma, Hollywood can't help but to keep feeding us the morally ambiguous vampire.

And evermore, we'll keep biting. - Alex Remington.