A price on cow belching could be just the shot in the arm Kiwi agriculture needs, Emeritus Professor Colin Campbell-Hunt believes.

Roughly half of New Zealand's emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) come from agriculture, principally the methane emitted by the animals that make up our dairy and meat industries, and the nitrous oxide that results from fertiliser and urine deposits on grazing land.

In this, New Zealand is a distant outlier among advanced economies: Ireland comes in a distant second at about 25%, while the largest emitters of agricultural GHG - the EU and US - produce 10% or less of their total emissions from agriculture.

New Zealand's agriculture sector is also unique for contributing more than half of our export earnings, so it would seem that the costs of reducing agricultural GHG would be particularly severe for us.

It is also the case that the prospects for significantly reducing agricultural methane emissions through improvements in animal productivity and breeding are unlikely to match the scale of reductions required to keep global warming within the 2degC that gives us some chance of avoiding runaway climate change.

For both of these reasons, the New Zealand Government claims that our ability to contribute to the global effort to reduce emissions of all GHG is unusually constrained, and that our best contribution is to purchase emission credits from countries that can cut theirs.

Both of these arguments need to be challenged.

The economic consequences to New Zealand of charging farmers for emissions do not stop with increased costs of dairy and meat production.

If applied equally by all countries, world prices for these commodities would have to rise, improving farm profitability.

Furthermore, the price required to reduce other, CO2, emissions could then be less, reducing the cost to New Zealand of buying emission credits.

The net effect has been estimated to actually improve our real gross national domestic income (RGNDI), the broadest measure of economic wellbeing, over a do-nothing, business-as-usual strategy, and improve it again between 2020 and 2050.

Why?

Because we gain more in higher prices for agricultural commodities and a lower price for CO2 than we lose in putting a price on agricultural GHG.

The alternative of not including agricultural emissions in global efforts considerably reduces these gains, by half in 2020 and by 80% in 2050, due to a doubling in the world price for CO2 that would be required to achieve overall reduction targets from CO2 alone.

The world community is also more likely than not to include agriculture, and especially livestock agriculture, in efforts to reduce emissions because the production of food that goes through the intermediate step of being eaten by a ruminant animal first produces far more GHG.

So New Zealand will most likely be challenged to reduce agricultural GHG emissions.

This may not be as difficult as we claim.

For example, Lincoln University professor Derrick Moot champions the use of lucerne (aka alfalfa) as a fodder crop to replace shallow-rooting ryegrass and white clover.

Where the latter rely on the application of fertilisers, lucerne fixes its own nitrogen, and produces 50% more dry matter from the same amount of water.

A recent article in The Economist reports efforts on a large American dairy farm to capture manure and extract methane that provides sufficient electricity to power all machinery and buildings on the farm. Excess gas is compressed and used to run the farm's fleet of 42 trucks.

One of the effects we should expect of putting a price on agricultural GHG emissions is to stimulate just these kinds of improvements in farm management.

Economic models show that if methane emissions could be reduced by 30% by 2050, at a cost of $70 per tonne of CO2-equivalent gas, the improvement in New Zealand's RGNDI is the highest of all the scenarios considered.

New Zealand's current stance on agricultural GHG reductions might be pithily restated as: ''it's too hard, and it would cost too much''.

Neither claim need be true if we manage to persuade the world to include these gases in the global effort to reduce harmful emissions.

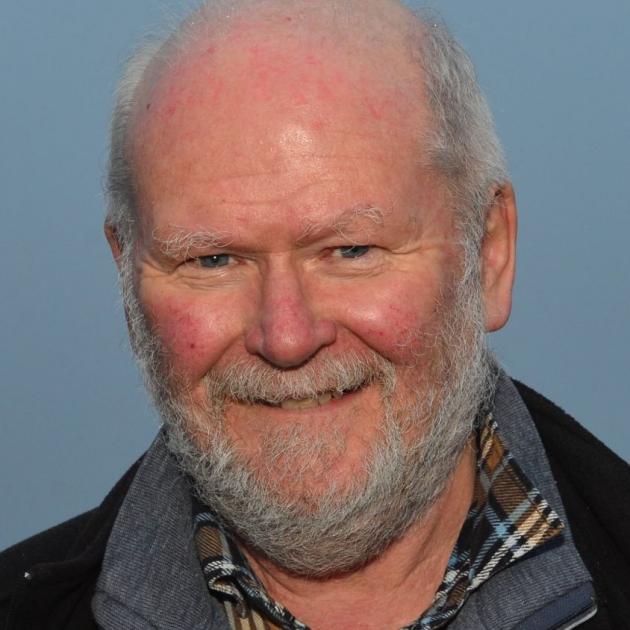

• Colin Campbell-Hunt is an emeritus professor in the Otago Business School. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.