In 2010, I stood for election to the Otago Regional Council, eager to contribute to striking the all-important balance between preserving what we value as a community and fulfilling our economic aspirations.

I came from a career in business where, likewise, striking this balance is the bedrock on which many successful companies are founded. Many of the disciplines I found in public enterprise are very similar to those in good private enterprise; none more so than the discipline of strategic and business planning. However, one major difference was the degree of stakeholder communication and engagement involved in this planning process.

Unlike private enterprise, where the shareholder is by definition the primary stakeholder, in public enterprise the stakeholders are the communities we serve.

My council's strategies are described in policy statements and resource plans which set out the terms on which our communities interact with their natural environment. The consequential business activities of the council and their financial implications are then set out in a specific long-term plan and refined in an annual plan.

Before the reform of local government in the late 1980s, what and how much the public heard from their councils had a good deal to do with the natural inclination of the elected head and their senior officials to communicate; and then, generally, on a one-way basis. Officialdom generally had little appetite for a two-way process.

With the reforming legislation of the late 1980s and subsequent amendments, a much more comprehensive set of minimum requirements for stakeholder engagement and consultation have evolved.

All council policy statements and resource plans are exposed to public consultation, as are the long-term and annual plans setting out proposed activities and the rating implications of those activities. Any proposed changes to those plans must also be exposed to public scrutiny and comment.

I recall a great deal of concern from elected representatives and communities that statutory consultation processes would slow up decision-making and create a great deal more bureaucracy. My observation is that the processes have, in the main, raised the quality of planning and decision-making and have certainly not hindered the ability of local government to undertake record levels of infrastructure development during the past 20 years to meet the demands of growth and rapidly rising community expectations.

Yes, the formal processes now required by statute have added more bureaucracy. Some of this is necessary if plans which better reflect community aspirations are to emerge. There is a view in both central and local government that significant streamlining can be achieved.

In the time since my election I have gained a high level of respect for the public consultation process. However, feedback I receive strongly suggests that this is not mirrored across our constituency. I often hear comments such as ''consultation is just a box-ticking exercise and your mind's made up before you start''.

When a proposal is put to public consultation, the only decision that has been made by the council is to do just that. The decision to abandon, proceed with modifications or proceed as proposed after consultation is an entirely separate process.

It is rare the final decision on a council proposal does not involve at least some change as a result of the consultation process. However, ironically, significant changes in a plan proposal are often heralded in the negative as ''back-downs'' or ''flip-flops'', implying that council has been brought to account by submitters - much more newsworthy, I guess, than simply representing it as ''local democracy in action''.

The regional council and our stakeholders are facing up to some major issues which have the long-term balancing of the regional economy and environmental wellbeing at their core. The water quality strategy proposed in water plan change 6A has seen these interests meet head-on. Deciding on the outcome will be an important item on the council agenda in early 2013. Consultation on the proposed Tarras irrigation investment, which would help the economic development of the area and produce some collateral environmental benefits (or vice versa, depending on your inclination), is under way. This will provide the council with interesting feedback on the community appetite for investment, with some rating implications, and potentially shape future thinking.

These issues are tough and with ever-increasing pressures around both the drive for economic growth and the state of the environment in Otago, future decision-making will be no easier. High levels of community interest focused on the issues at hand will be vital as we search for sustainable solutions.

It is often said democracy delivers us the government we deserve. Similarly, it could be said the scope and quality of community involvement in the consultation process delivers the decisions we deserve. But there is one caveat.

Consultation involves careful listening and consideration. Agreeing with and being able to incorporate community contributions is very satisfying. However, not agreeing with points raised or not adopting a submitter's proposition does not invalidate the process. We cannot deliver what people want all of the time. Ultimately, politicians at all levels are duty bound to do what they believe to be right.

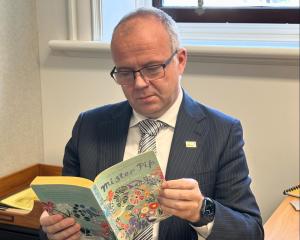

• Trevor Kempton is an Otago regional councillor and former managing director of Naylor Love Ltd.