In New Zealand, we enjoy a stable democracy with a sound legislative and judicial system. Our parliamentary and legal frameworks are substantially based on the British system with common law principles dating back to the Magna Carta in 1215.

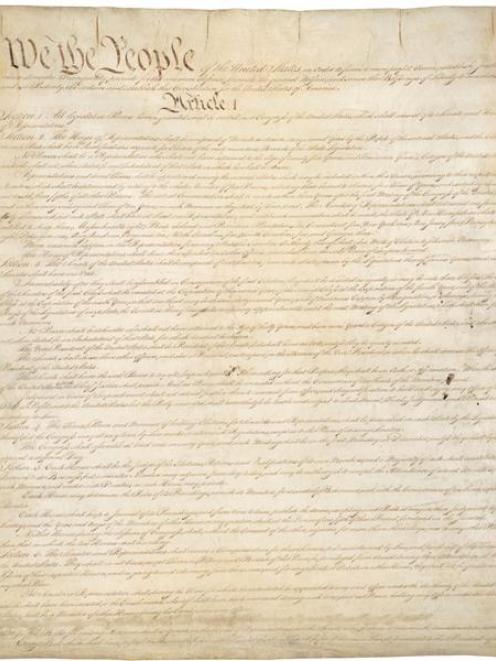

Neither Britain nor New Zealand have written constitutions in contrast to the majority of countries. Frequent reference is made to the United States' Constitution, which is written. A constitution is basically the set of rules, usually written down, under which a country is ruled. In simple terms, an unwritten constitution provides flexibility as opposed to written constitutions which can have significant rigidity.

The benefit of an unwritten constitution is that Parliament is sovereign and the judiciary applies and interprets the laws that Parliament makes. With a written constitution, such as in the United States, the Supreme Court is frequently asked to resolve arguments relating to constitutional issues.

One of New Zealand's strengths is that the Westminster model of government has been our guiding light for more than 160 years. During this time, we have developed as a nation in our own unique way with much to be proud of. Our sense of egalitarianism was once a major strength, perhaps less so now. The welfare state model established in the 1930s and 1940s was farsighted and evidence then of strong political and social consciences.

Despite the market economy of the past 30 or so years, governments still display social awareness evidenced in providing assistance for those less well off, with an example being Working for Families. The Bill of Rights Act 1990, the Human Rights Act, Race Relations Act and a multiplicity of legislation has ensured New Zealanders are well protected under the law in an equal and non-discriminatory way which is consistent with and reflects our national diversity.

However, given the power our unwritten constitution confers on Parliament, we need to be assured of and expect our politicians to act with probity and in the best interests of New Zealand. Our Parliament doesn't have the equivalent of the British House of Lords to provide some semblance of checks and balances on major issues. The New Zealand equivalent (the Legislative Council) was abolished in 1950.

Legitimate public concerns are expressed at times in the way, for instance, emergency legislation, is rushed through Parliament in great haste. Legislation was passed recently affecting the rights of caregivers and specifically denying any right of challenge to this law in the courts. The Hobbit legislation, where the Government overrode established employment law, was also not consistent with the standards we should expect from our politicians.

MMP to some extent helps to ensure the integrity of Parliament. There may also be a case for reinstating an Upper House in our Parliament where matters of national interest could be given a greater depth of consideration before there is any final decision by the government. Perhaps, a parliamentary code could be instituted to curb legislative excesses. The use of referendums would also enhance the democratic process.

A Constitutional Advisory Panel has been seeking the views of the public, with a deadline for written submissions next Wednesday. The origins for this panel date back to a coalition agreement between the National and Maori parties at the last election. There is a dominant Maori composition on this panel which not surprisingly has raised questions about the panel's impartiality. Also, whether a political agenda is driving this process rather than something that is conceived to be in the national interest.

It seems there is not a strong case in New Zealand for a written constitution. In general, New Zealanders are fair, tolerant and inclusive.

Our institutions overall are very sound, despite occasional concerns from time to time. Our unwritten constitution has served us extremely well and there appear to be no obvious reasons why it shouldn't continue to do so. A written constitution has the potential to be divisive and problematic, as evidenced in Egypt recently, where a constitution was drawn up strongly favouring a particular group, leading to disenchantment from the population at large and the overthrow of the government.

Recently, in the United States, Louis Seidman, one of America's leading constitutional scholars, in a book On Constitutional Disobedience actually advocates discarding the United States' written Constitution. Tom Bingham, a former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, in a book Tom Bingham on the Rule of Law published in 2010, stated ''to substitute the sovereignty of a codified and entrenched Constitution for the sovereignty of Parliament is, however, a major constitutional change. It is one which should be made only if the British people, properly informed, choose to make it.''

What would happen in New Zealand with a written constitution is that the sovereignty of Parliament would largely be usurped by the courts and could result in never-ending legal arguments and create unnecessary dysfunction and disharmony in our political institutions.

Our unwritten constitution has served us well. May it continue to do so.