"We can get away with this, we really can. I really believe that people need to do what they're asked to do. There's still time. It [ICU capacity] will be under pressure but we will not be overwhelmed and the ghastly scenarios we've seen in other countries need not apply here." - Dr Andrew Stapleton

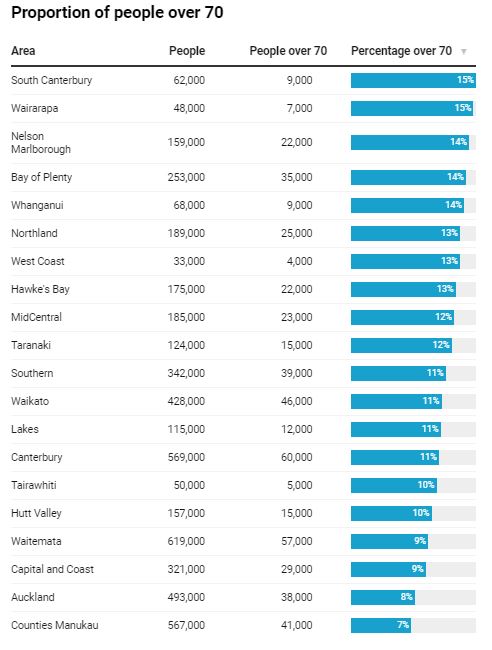

What shape are New Zealand's 20 district health boards in, heading into potentially the greatest strain on their resources with a Covid-19 outbreak? Each of the 20 boards' geographical DHB boundaries spanning the country has a unique age demographic and health care system.

How many hospital beds do they have? How many intensive care beds? How many infections could they handle? How many people over 80 years - at which point Covid-19 death rate spikes - do they have? Tom Dillane and Chris Knox crunch the numbers.

The state of NZ's DHBs

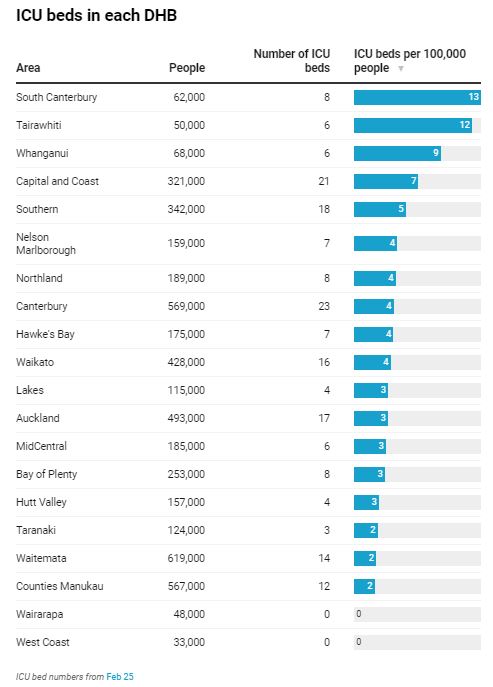

As of February 25, the Ministry of Health reported just 173 total ICU beds nationally.

This was scraped up to a total of 233 including their high dependency care beds and cardiac care unit beds, with respirators.

Here's the breakdown per DHB:

However, this reported total of 233 ICU beds across the county's 20 DHBs is a fluid number explains Dr Andrew Stapleton - who is chair of the NZ college of intensive care medicine and sits on the ANZICS Covid-19 working group.

"The 170 number came from the ministry ringing everyone one day a few weeks ago and saying 'How many beds have you got today?'" Stapleton said.

"That number goes up and down as I say depending on what day of the week - because we deliberately have more staffed ICU beds during the week.

"And then we stop doing that at the weekend when there aren't elective surgeries. There are times when there are nursing shortages.

"You've only got as many ICU beds as you've got nurses, so that number does vary from 170-odd to 220-odd - which is probably the more authentic number when we're fully staffed."

On March 20, an updated Ministry of Health stocktake found a maximum of 563 ICU capacity beds in a total restructure of the country's hospitals.

This will in theory be done by repurposing 231 further bed spaces in occupation therapy wards and emergency departments.

Another 99 beds could also be repurposed to care for ventilated patients such as in high dependency units and gastroenterology units.

The breakdown of which hospitals and DHBs will be providing these potential extra beds will be released this week, Stapleton said.

The New Zealand Herald has analysed the age demographics, Covid-19 infection rates based on age, and hospital bed numbers and ICU numbers of different DHB regions.

We have used the same infection and hospitalisation rates as cited in the series of modelling reports the University of Otago has produced for the Ministry of Health over March.

The ICU bed requirements cited in this article are based on the University of Otago estimate that 4 per cent of symptomatic cases of Covid-19 (those who display Covid-19 symptoms) will likely require an ICU bed.

We must stay under approximately 24,000 Covid-19 infections nationally at any one time to make sure to make sure we do not max out our 500-odd ICU beds.

It should be noted that the numbers are conservative because they represent New Zealand's ICU and bed capacity on a single day.

A Covid-19 patient admitted to ICU typically stays 15 days, meaning the system will get even more stressed if new cases continue at their current daily rate, and the lockdown does not flatten the curve.

Below are four scenarios on how Covid-19 infections could track within the New Zealand population.

It includes a best-case scenario, which the University of Otago study doesn't even entertain, but which the Government and some intensive care doctors are optimistic of.

The remaining three scenarios broadly summarise the University of Otago's March modelling of the varying degrees of strain New Zealand's health system and ICU capacity could face over the next year.

They are: a scenario manageable within the Ministry of Health's planned ICU capacity increase in 2020; a scenario that will exceed capacity but that is conceivably manageable if ICU space is even further bolstered in 2020, and a crisis scenario comparable to Italy where ICUs are thoroughly overwhelmed.

Scenario 1: We'll be fine and within current capacity.

No DHBs will reach their ICU threshold under this scenario: 0.025 per cent of the population is infected at once, equating to 1200 Covid-19 positive cases and 24 ICU beds.

The March 25 midnight lockdown of New Zealand society aimed to have every Kiwi currently infected with Covid-19 infect zero other people from then on.

They will infect those they're living with, in their bubble, but those people will also infect no one else - theoretically stopping any further spread after they have recovered over a fortnight in isolation.

Without isolation restrictions, people infected with Covid-19 infect three other people on average.

As of Monday, New Zealand had 950 confirmed and probable Covid-19 cases, which hospitals can handle within existing capacity.

This is a number that we can handle without changing a thing with our hospital capacity.

New Zealand's College of Intensive Care Medicine chairman Dr Andrew Stapleton says if Kiwis comply with level 4 restrictions the "best case scenario" is we have 1000-2000 cases throughout the population.

"If in the next three weeks we have more than three or four thousand patients we're going to struggle in ICU even with extension plans. But if those numbers come over time, flatten the curve, then we can cope," he said.

"Social media amplifies the horror of the worst-case scenario and it's very easy to forget the vast majority, 99.5 per cent of patients under the age of 70, will get better and be just fine and, even better, they'll be immune in the future from Covid."

But we won't know if the lockdown is working for a couple of weeks, Stapleton said.

"Every three to five days we're likely to double [cases] because of the community spread that we assume is already occurring," he said.

"In about nine to 12 days we will see what happens next and if everyone stays at home the virus can't spread.

"I think the best-case scenario will be 1000 cases. If everyone complies with the lockdown maybe 2000 cases and then we should see it level off pretty sharply after that.

"That's been the experience of other countries who've imposed strict lockdowns.

"We can get away with this, we really can. I really believe that people need to do what they're asked to do. There's still time. It [ICU capacity] will be under pressure but we will not be overwhelmed and the ghastly scenarios we've seen in other countries need not apply here."

On March 27, director-general of health Dr Ashley Bloomfield said the number of people with the disease was expected to start to level off in roughly 10 days, or this coming week.

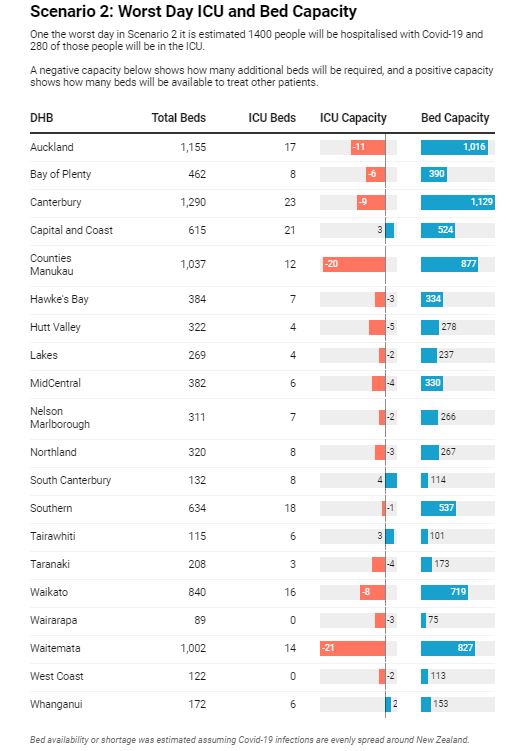

Scenario 2: We'll be at the limit of our capacity of 233 ICU beds.

Around 30 per cent of the population gets infected. Peak day will be 7000 cases in week 47 after the virus was confirmed in NZ, requiring 280 ICU beds.

If New Zealand were to have around 7000 positive cases of Covid-19 on our peak infection day, our health system as it is structured right now would be over capacity.

But if this were to come at the end of the year, as projected in the University of Otago study, we would likely have raised the system's capacity to the maximum of 563 makeshift beds.

New Zealand has 233 ICU beds as it stands. A 30 per cent infection rate of our 5 million population would require roughly 280 ICU beds on the worst day.

But ICU beds across New Zealand's DHBs are normally near capacity on a normal day - with 80 to 90 per cent of those beds in use on a normal day depending on the time of the week.

Although there are efforts right now to delay elective surgery to provide extra ICU capacity for Covid-19 patients, at least half of New Zealand's existing 233 ICU beds will still be occupied by non Covid-19 patients.

"It's really difficult to answer that," Dr Stapleton says of New Zealand's typical ICU occupation number.

"It depends whether it's the weekend, it depends if it's school holidays and the surgeon who's doing surgery is away.

"But if I had to give you a number it's about 80 to 90 per cent occupied. So that's 80 per cent occupied of the 220-odd beds we've got.

"So that quickly shows you we don't have much additional capacity,"

Far fewer cars on the roads during the lockdown will also relieve ICU.

"The fact that people are staying at home also means they are not crashing their cars, in practical terms," Stapleton said.

"So things that are not happening in terms of the lockdown, that will reduce pressure on ICU beds."

But among those most at risk for regional capacity would be West Coast and Wairarapa, which have no ICU beds.

West Coast DHB general manager Philip Wheble said over the past few weeks they have been setting up an isolation unit at Grey Base Hospital specifically for caring for any Covid-19 patients.

The option to transfer patients to Canterbury after consultation with a clinical specialist is also there for West Coast DHB.

"Over the past few weeks, we have been working with public health, infection prevention and control, primary care, emergency response, communications and clinical teams to plan and create pathways of care for any Covid-19 patients that best suit our region and population," Wheble said.

On March 29, New Zealand's first death from Covid-19 happened in a West Coast DHB hospital.

Anne Guenole, 73, died shortly after testing positive for Covid-19.

She had been admitted to Grey Base Hospital in Greymouth on March 25 with suspected influenza.

Wairarapa DHB chief executive Dale Oliff also cited the options they have if a Covid-19 patient does need an ICU bed.

"Wairarapa District Health Board does not have an ICU but it does have a limited number of beds in its High Dependency Unit, and ventilation capability where we can stabilise patients to be transferred to our tertiary provider as soon as we are able," Oliff said.

According to the Australia and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, when private ICUs are included in the data New Zealand lags well behind world ICU standards, and the capacity has been falling.

Between 2011 and 2018, the number of ICU beds per 100,000 people declined from 5.98 to 5.14 in New Zealand, whereas in Australia they increased from 8.50 to 8.92.

In Europe, the average is about 11.5, and Germany has close to 30.

Italy, where more than 11,000 have died from Covid-19, has 12.5 ICU beds per 100,000 people.

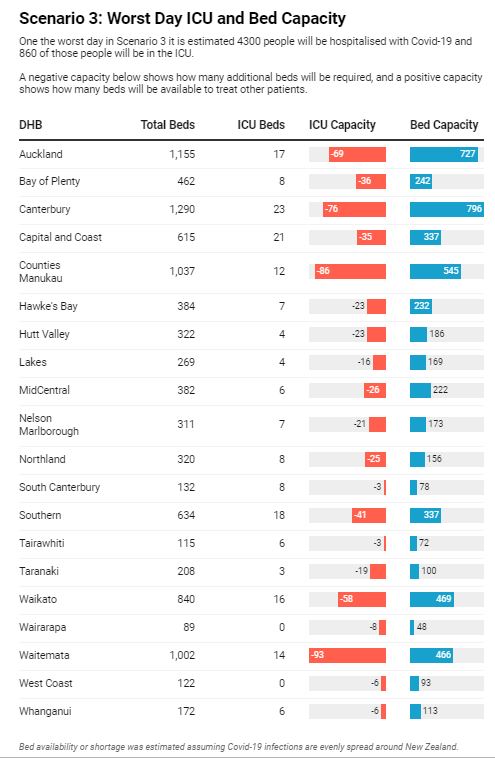

Scenario 3: Overload of current ICU capacity and exceeding NZ's projected max of 563 beds

A drastic restructure of the health system to cope, 53 per cent of NZ's population gets infected over the course of Covid-19 spread. Peak day will be 22,000 Covid-19 cases in week 27 after the virus was confirmed in NZ, 860 ICU beds needed.

This scenario would leave New Zealand on the brink of its improvised max ICU capacity of 563 beds.

There would be 500-odd ICU beds needed for Covid-19 patients, leaving only 60 or so beds for other patients who needed them for other illness and injury - which is a conservative number.

By the time it gets to this point there will undoubtedly be transportation of Covid-19 ICU patients around the country between hospitals in different DHBs.

Every DHB, with the exception of Tairāwhiti, would have exceeded their normal ICU capacity and would be thoroughly utilising the improvised ICU beds cited in the Ministry of Health's 563 max ICU bed number.

Stapleton admitted there is concern about the varying ICU capacities of the DHBs but a plan for air transportation of Covid-19 patients is in place - drafted by his colleague Dr Alex Psirides.

In such Covid-19 air transport situations between DHBs, the patient should wear a surgical mask, and all unnecessary equipment should be removed from the aircraft.

As a minimum precaution, aeromedical crew should wear personal protective equipment including a surgical mask, long-sleeved fluid-resistant disposable gown/overalls, disposable gloves and eye protection (goggles or face shield).

Stapleton said rescue helicopter operations around the country were "typically" responsible for transporting ICU patients, and there was a "well established transport network" for critical patients.

"If we're truly overrun transport won't be possible because there won't be anywhere to transport sick patients to and they will die," Stapleton said.

"But we can even it out and spread it round the country until such times as everyone is overwhelmed. By the time Wellington is overwhelmed, Wairarapa will be overwhelmed as well, so in a way it will be no different.

"They won't be able to receive care wherever they are to the usual high standard."

Auckland Rescue Helicopter Trust's medical director Dr. Chris Denny said they are fully aware of the list of criteria and are ready to transport patients now when needed.

"We have six helicopters stationed at two bases, Auckland and Whangārei, who provide our aeromedical services 24/7/365," Denny said.

In the case of a Covid-19 outbreak where patients had to be transported around the country to different hospitals, Deny said several factors would apply to their own patient capacity.

"The number of trips we can complete each day will depend upon distance, requirement for personal protective equipment (PPE), the requirement for resuscitation of the patient prior to transport, weather and the need to decontaminate the transport platform of the aircraft upon return to our base of operations," Denny said.

Auckland Rescue Helicopter Trust operations manager Roger Hortop noted that their helicopters are capable of flying anywhere in New Zealand, but more likely in the North Island subject to payload and to weather conditions.

ANZICS Dr Stapleton added if New Zealand's ICU capacity did reach its max limit of 500-600 improvised beds, transportation of patients would occur based on the same criteria it does now between hospitals for intensive care patients.

"Yep by helicopter, ambulance or plane depending on the sickness of the patient," Stapleton said.

"They'll come to hospital if they're feeling very sick, they'll be assessed and they will either be sent back home again, or admitted to hospital.

"Then they will be monitored in that hospital and if they deteriorate further and that hospital can't cope with it the call would go out to the tertiary hospital in exactly the same normal way as it does for any patient with pneumonia, for example, who pitches up out of area at the moment."

Yet, Stapleton admitted the prospect of a particularly bad Covid-19 outbreak in one region of the country was definitely a problem ANZICS had mulled over in past weeks.

"There's concern but there's a plan to move these patients if necessary," Stapleton said.

"ICU's a precious resource at the best of times. So if they're assessed and they need it, and they [the hospital] are at capacity they will be moved. But there will be capacity if people stay at home."

Keeping a patient in an ICU bed roughly costs $2500 - $3500 per day.

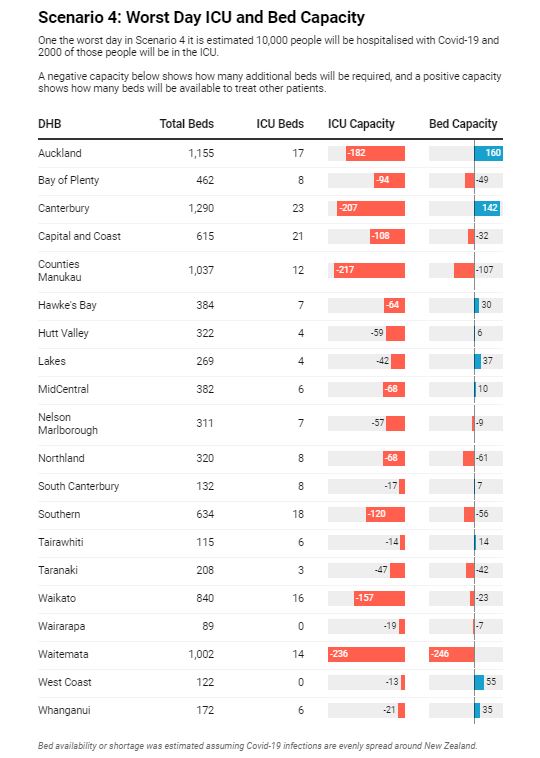

Scenario 4: All DHBs overwhelmed by a need for thousands of extra ICU beds.

It will get very bad. No chance of coping. 72 per cent of NZ's population get infected. Peak will be 50,000 cases in week 17 after the virus was confirmed in NZ, 2000 ICU beds needed.

If New Zealand were to reach even a 1 per cent Covid-19 infection rate across the population at one time, ICU bed demand would exceed capacity by at least 500 beds.

If we reached a 10 per cent infection rate at one time, we would be 10,000 ICU beds short.

The University of Otago study has a 72 per cent infection of New Zealand's population over the course of Covid-19's spread requiring 2000 ICU beds. The worst day will have 50,000 Kiwis infected at once.

No one at the Ministry of Health has indicated that this will be possible within the next six months.

With all 20 DHBs at capacity, drastic measures like those seen in Italy would have to be taken.

This week in Italy, more than 11,000 people had died from Covid-19 and more than 100,000 were infected.

In February, the Italian College of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care published criteria their doctors should follow when making the awful decision of who should receive intensive care treatment.

The guidelines compare the moral choices Italian doctors may face to those encountered in wartime triage and the zone of "catastrophe medicine".

The virus has taken a heavy toll on Italian doctors and nurses. More than 6000 medical staff have been infected and nearly 50 doctors have died.

A dozen Italian doctors recently wrote a joint letter, saying health systems worldwide had to be switched from hospital-based care to home-based care in the battle against Covid-19.

"Paradoxically, at a time when most of Italy is shut up at home, hospitals are the only places where thousands of people find themselves brought together in close contact," Pierluigi Lopalco, a professor of hygiene at the University of Pisa, told La Repubblica newspaper.

A New Zealand-developed "1000minds" software tool is already used to guide clinicians dealing with a surge in cases in Italy, and will be rolled out across intensive care units here this coming week.

The "1000minds" software arose from research at the University of Otago and is already used in New Zealand to decide the most needy patients for some elective procedures.

The software works by first presenting patient vignettes to clinicians. In deciding who should be treated next a set of criteria is worked out, and then weighted according to importance.

This information is used by the software to create a score for real-life patients.

That score would then help a group of intensive care doctors decide who should get a bed, when there aren't enough to go around (it would only be used for Covid-19 patients).

Stapleton declined to go into detail about what factors helped score patients, but said some were obvious.

"Extremes of age, extremes of weight, extremes of chronic disease - clearly they are all factored into that," he said.

"It is a diagnostic aid. It is absolutely not a computer making the decision between life and death.

"You have one bed and four patients - who are you going to give the bed to?

"The tool will aid that decision, it will not make that decision."