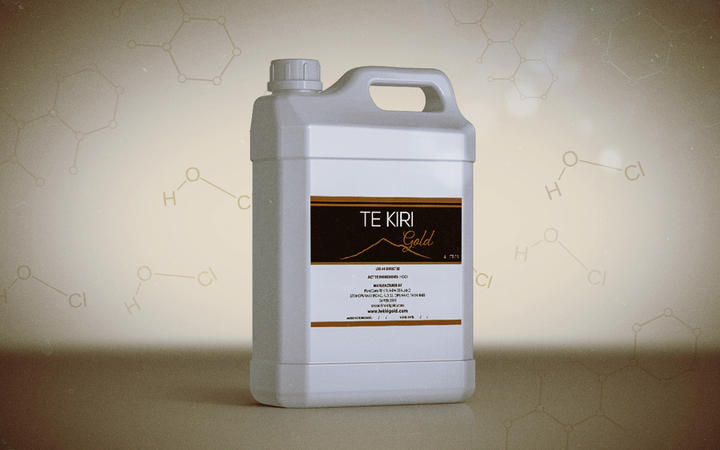

A woman who was convinced drinking bleach water Te Kiri Gold would save her dying father is devastated it is still for sale, even after one of the owners - a doctor - was deregistered for testing it on 500 terminal cancer patients.

Emma Foley can't remember who it was that first told her about the miracle liquid that would cure her father's cancer. Probably someone from the farming community in coastal Taranaki, where her family lives and where the product, Te Kiri Gold (TKG), is still made and sold.

It didn't matter who told her about it, anyway, because it was exactly what she'd wanted to hear; that something would save her dad from the cancer that had formed in his kidneys and crept through his body, into his brain, then everywhere else, after doctors said nothing could.

Foley, a 40-year-old mother of two who wears her hair in an orange bob, says that the people who sold TKG to her family assured her it would cure her dad's cancer. "It wasn't, 'It might cure your dad', or, 'It might help him'. It was, 'It will fix him'. And that's the stuff you're so desperate to hear."

So the Foley family gave TKG owner Vern Coxhead money, and hope, and insisted a sick Kevin Foley drink the bleach water that made him gag. As advised by the company, he mixed TKG with milk (chocolate flavoured) to mask the taste - 285ml, morning and evening. The family smuggled the product into Auckland City Hospital while he was being given blood transfusions and platelets. He drank it in the hospice, the day before he died.

End stage cancer patients facing the prospect of death are considered vulnerable to manipulation or exploitation, experts say. In this case, the family was vulnerable, too. Emma Foley - afraid her father was going to die and searching for a way to save him - had joined a Facebook group where people taking TKG shared cancer survival stories. "I believe so much in it… It's a miracle product," one woman wrote to her. On the product's website, a (now-deleted) testimonial claimed TKG helped a man with "a rare aggressive cancer" into remission (he has since died). Others talked of delaying surgeries or refusing drugs because they believed the TKG was working. "Shane has decided against chemo and has just started taking Te Kiri Gold… We are hopeful that this will be the miracle cure…" one family wrote on a Givealittle fundraising page. "Reports we have heard so far sound amazing!! A bit of hope to cling to…"

Emma Foley was in regular contact with Coxhead's daughter, Michelle Paton, who told her, "Most of the people we treat have been completely discharged from the medical profession". Screenshots from the Te Kiri Gold Facebook group, run by Paton, show a range of discussions - from parents giving TKG to a 12-year-old with a brain tumour, to a woman who, "having exhausted every other avenue", planned to take the substance intravenously.

Foley says her father, who also had chemo and immunotherapy, was dubious about TKG and did not take it the entire time he was sick. She says she was the one who pushed him to use it. "I think Dad probably would have given up on it long ago if it wasn't for us saying, 'Look, look at this email', 'Look at this post on the Facebook group,' or, 'Come on, it's worth a shot, right? Here's someone whose platelets were this, and that's like you, and they're better now,'" Foley says.

She genuinely thought TKG would save him, and was dumbfounded when it didn't. Looking back, Foley is embarrassed she believed in it so fervently. "You can't really accept the alternative, I guess. I think I'm pretty logical about things, but when you have people telling you for sure, 'I was untreatable, there was nothing [doctors] could do for me and now I'm free of cancer', and [TKG is] the only thing that changed... You think, 'Well, we're not gonna miss out on the chance.'"

With hindsight though, she believes TKG is a scam. She wonders whether its producers genuinely believe in it, or are just out to make money. She's angry that she was convinced it would help her dad, and she's angry that there could still be other people out there being convinced of the same. She wants it to stop.

Foley estimates the family spent up to $7000 on TKG before her dad's death at the end of 2017 (Coxhead disputes this, and says it was closer to $2000). In that same year, Pure Cure, the New Zealand company that produces TKG, sold approximately $327,000 worth of product and two companies with the same name were incorporated in the UK.

Emma Foley says she heard nothing from Dean Feller, Paton or Coxhead after her dad died. But in December 2018, she received a Facebook message from Dean Feller's wife. It was a link to a fundraising website, asking for donations to help cover the cost of returning to the US from New Zealand after Dean Feller was deregistered.

Now, the TKG Facebook page has been shut down and testimonials have been removed from the website, as have some of the false claims about its supposed ability to fight cancer. But TKG is still for sale online, courtesy of Pure Cure's other shareholder, South Taranaki dairy farmer Vern Coxhead.

How is this still allowed? Instead of being marketed as a medicine, it's registered as a food, and sold as water.

***

Te Kiri Gold's active ingredient, hypochlorous acid, is used to treat water, in the sterilisation of swimming pools, as a topical wound treatment, and as a disinfectant in the food and beverage industry. Back in 2016, Coxhead told media he started using it on the farm to combat mastitis and foot rot in his cows.

The TKG website claims the compound "reverses oxidation", kills mutated, abnormal or foreign cells and brings the immune system "again to life". Over the phone, Coxhead calls the product "your immune system in a bottle".

An "informed consent form", given to people using TKG during Dean Feller's unauthorised trial, says, "We believe the solution, TKG001, to be of significant potential value in helping individuals with cancer. A large body of published research indicates that this should be the case."

But that research does not exist, says Professor Mark Hampton, director of Otago University's Centre for Free Radical Research. Hampton says hypochlorous acid is an oxidising agent - claims by the company selling TKG that it "reverses oxidation" are false.

In fact, the professor says, TKG is nothing more than diluted chlorine bleach. "It's about 1 percent of what you would find in a bottle of Janola that you've got off the supermarket shelf". In terms of cancer therapy, there would be no benefit in taking TKG for anyone with any type of cancer, he says.

Furthermore, drinking the product would lead to the hypochlorous acid immediately reacting with the cells in a person's mouth and throat, rendering it inactive. The same thing would happen if a user mixed it with milk, as is recommended by Pure Cure, and as Emma Foley's dad did. Hampton says the acid would react with the milk's proteins, leaving nothing but foul-tasting, oxidised, salty milk - the stuff that made a dying Kevin Foley shake violently and gag.

When asked about the ethics of selling a product like this, Hampton said it would be nice to think the company owners believed they were helping desperate people, rather than exploiting them for financial gain. "However, I believe people selling products like this have an obligation to find all available information, seek expert advice if necessary, and stop when it is clear the product will not work. Ignorance is not an acceptable defence when the science is clear."

***

In December 2016, a Stuff article reported that former All Black Sir Colin Meads, who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in August that year, credited TKG "with keeping him from death's door". Coxhead said interest in the product skyrocketed after Meads' endorsement.

But since then, multiple complaints have been made about TKG - including to the Commerce Commission and the Health Ministry's medical safety authority, Medsafe. After investigations by both the Herald and Stuff, Medsafe warned Coxhead that he appeared to be unlawfully supplying an unapproved medicine. By May 2017 all therapeutic claims, testimonials and links to media articles about TKG had been removed from its website.

The Commerce Commission complaint was merged with one related to water filtration businesses in 2018. No further action was taken against TKG, because, according to the Commission, "its website/social media presence indicated that it was not actively trading at the time".

But the company was still trading. In July last year, Medsafe told Stuff it would review whether the continued sale of TKG was compliant. After the review was completed, a spokesperson told RNZ that Medsafe "did not find evidence of therapeutic claims that would trigger further regulatory action". Because TKG is now marketed as water, rather than as a medicine, the investigation was transferred to the Ministry for Primary Industries' agency Food Safety.

Today, the product can still be bought online, though Coxhead says sales have slowed down to a trickle and the company is in debt, after covering Dean Feller's legal costs. When Coxhead speaks to RNZ, he chooses his words carefully. He no longer claims it will cure, or even help treat cancer. "I can't make any claims," he says.

But there's a work-around. "If someone else tells you something, then that's fine," he says. Sometimes, when a prospective customer contacts Coxhead wanting to know more info about using TKG as a cancer treatment - how it's worked for others - he gives them the contact details of pre-existing users who, he reckons, can say whatever they like.

In September 2017, months after therapeutic claims were removed from the TKG website, Emma Foley messaged Coxhead's daughter Michelle Paton, who ran the TKG Facebook page, questioning its efficacy. "We had a not very positive scan result yesterday. Dad is naturally questioning if he should continue with TKG. We believed TKG stops the cancer growing. [Are] there any results from the trials you have been doing that are seeing people cured?"

Paton replied, "Yep there are people that have cleared up with TKG alone…" and gave Foley two phone numbers. One, she said, belonged to a man in Patea who had a brain tumor (an obituary for a man with that name ran in the Taranaki Daily News in 2018). The other person was Royce Mattock.

***

Mattock calls Coxhead his angel. "He saved my life," he says over the phone, before enthusiastically launching into the story of how he was cured by TKG. Five years ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer: A surgeon told Mattock he was "too far gone", and to "go home and sort your will out".

"Well flippin' hell, I broke down and cried straight away," the Taranaki builder says. "That's the last thing you want to hear, you know, that you're doomed to die.

"Coming back [from hospital] my partner says, 'Just drive the car into the bank, we'll both go together.' I thought, there must be other options out there, there's gotta be."

And there was, he says. Through his best friend's uncle, he found out about Te Kiri Gold. After two and a half months of taking it, he saw the surgeon again. The cancer was gone and Mattock told the doctor about what he had been taking. "But he couldn't say anything because they're sworn by their code of practice with Pharmac and all that." (Pharmac, the New Zealand Government's drug buying agency, does not have a code of practice by which doctors or any medical practitioners swear. Later, Mattock says Pharmac doesn't want to admit that there are "cures out there because they lose too many billions of dollars." Coxhead also repeatedly refers to "big Pharmac" when he speaks to RNZ.)

How many people has Mattock told this story to? He says he's spoken to a "a few" who've since started taking the solution and are "rapt". He regurgitates the same information as Coxhead - that TKG was discovered in Russia and works the same way as your immune system.

A four-litre bottle of TKG currently costs $100. Back when Foley's father took it, it was double that and he was advised to drink a bottle a week. Other users who have spoken to RNZ report taking it at the same dosage.

Mattock says he recommends it to anyone with cancer. "I just say to people, 'What have you got to lose? You know, it's only $100 for four litres and it'll last you for over a month.' It's quite cheap in that respect and yeah, I truly, strongly believe in it."

***

It's understandable that people facing the possibility of death might search for something to give them hope. And this is what can drive terminal cancer patients and their families to believe in miracle treatments like TKG, says Neil Pickering, an associate professor of bioethics at Otago University.

The medical council's statement on informed consent - a key principle of medical ethics - makes it clear that if a treatment lacks scientific evidence, this must be explained to the patient. In the case of Te Kiri Gold, the Health Practitioners' Disciplinary Tribunal found that had not been done.

But what if the person providing the treatment - in this case, Dean Feller and Coxhead - does believe there is evidence it works?

Pickering says this is not uncommon, but that such beliefs tend to be built around theoretical frameworks backed up by shaky science. "Sometimes there's a little bit of evidence, but it's very often anecdotal, and in some cases it may be that the people giving the anecdotal evidence have the same beliefs [as those selling the product]." Coxhead claims evidence supporting TKG is "just pure science". When asked about people who have died of cancer, despite taking the substance, he says he doubts they actually took it. It's more likely, Coxhead says, that the cancer sufferer just told loved ones that they took it, to "get them off their back". Alternatively, if the patient did take TKG as advised, Coxhead suggests the person died of something other than cancer.

Pickering says claims of a cover-up are commonly made to explain why a product or therapy is not accepted by the wider scientific community. "I've certainly seen that claim made in the cases of other alternative therapies. Also that it's very difficult to get funding to do the research and so on, so that the impression you get is that there's a downright conspiracy." In the high-profile case of Liam Williams-Holloway, a Central Otago child with cancer who was treated (unsuccessfully) with a machine called the 'Quantum Booster', claims about the machine's inventor included that his discovery threatened too many vested interests and was therefore deliberately kept from the public. Pickering adds that it is often claimed that these conspiracies to suppress cures for disease are spearheaded by 'big pharma'.

On the TKG Facebook page, in response to a Stuff article criticising the solution, one user characterised the reporting as "yet another case of big pharma using their connections and money to take down our little farmer".

***

On 3 May 2017, at the request of Medsafe, TKG customers were sent a letter informing them that the solution was not a medicine. Around that time, via email, Medsafe compliance manager Derek Fitzgerald told Coxhead the authority was concerned that therapeutic claims made about TKG could lead "to some people not having the conventional treatment they should have". Coxhead says he would never advise anyone against having any treatment.

In September 2017, after the investigation into TKG was transferred to Food Safety, Medsafe forwarded the authority a complaint about further health claims made on a closed TKG Facebook page. In a statement, the authority told RNZ a link between the Facebook group and TKG company Pure Cure "could not be established".

RNZ asked Medsafe if it was permissible under the Medicines Act for Coxhead to give prospective customers the contact details of other TKG users who claimed to have been cured of cancer by the substance. Despite Medsafe being responsible for administering the Medicines Act, a Ministry of Health spokesperson initially referred the question to Food Safety. When pressed, Medsafe provided RNZ with a statement saying that advertising an unapproved medicine by testimonial is not permitted under the Medicines Act.

When she first spoke to RNZ about the death of her father, Emma Foley wondered whether Coxhead truly believed in TKG, or whether he was just out to make money.

But Coxhead insists that by continuing to sell the product he is, in fact, losing money. "It's not easy and my family would rather I didn't do it at all." But his fanatical belief that TKG cures cancer weighs on his conscience. In his mind, continuing to produce and sell it means saving lives. "I would rather run away and hide and just say look, I don't do it anymore. But then you're not on the phone when those people ring me and ask for it. So, what do I say? That's the problem, Susan. That's my dilemma."

He says helping mankind is what every child aspires to do. "But it's not an advisable thing, I tell ya. Don't do it." When asked if he thinks there's a possibility he's wrong about TKG - and that experts like Professor Mark Hampton are right - he says, "I know I'm not wrong."

***

Emma Foley recently attended a funeral, where family members spoke fondly of the last few days they had with their loved one.

It made her wonder if the final days she spent with her own dad have been different if she'd accepted his death was imminent. She'll never know, because she didn't accept it. She believed the TKG would save him, like it had saved the other users she had spoken to.

She wonders how she'd have coped without that blind hope the bleach water gave her. She says the thought terrifies her. "But it's still not ok."