Both barrels of a shotgun were fired into Donald Fraser’s chest at close range – so close, in fact, that they left two separate holes.

The force of the blast was so violent that Fraser’s body was bounced off the bed where he had been drunkenly sound asleep, and he ended up lying partly face-down on the floor, with blood soaking into the carpet.

His wife, Elizabeth Fraser, claimed that she had been asleep alongside her husband, and less than an arm’s length away, when Donald was killed.

So why was it that when police looked at her nightgown, there was not a speck of blood on it?

How could Elizabeth’s claim stack up when her side of the bed looked like it hadn’t been slept in, and there were still ironing creases on the unused pillow?

Why was it that, as a massive police investigation began, the word on the street in Christchurch was that Fraser probably had it coming?

And who was the mystery woman in the case, referred to as "Miss X" by the tabloid newspaper Truth, enigmatically represented in its pages by a photograph of a long-haired woman wearing a mask?

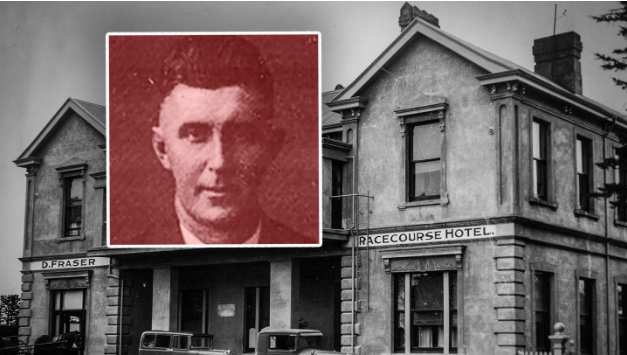

Fraser, the publican of the Racecourse Hotel in Riccarton, died in the early hours of November 17, 1933.

It was a brutal, deliberate killing, carried out in semi-darkness by someone who was good with guns and knew what they were doing.

After Fraser was shot, the killer disappeared into the night. All these years later justice is yet to be served - the murder remains unsolved.

The murder scene

The bedroom where Fraser was killed is still much as it was, on the first floor of the hotel, opening onto the balcony at the front.

In the place of Fraser’s furniture there is just a single bed and the fireplace near where his body lay has been covered up, but it is identifiably the murder scene as described in the police files of the 1930s.

The Weekend Herald revisited the scene in preparation for a new podcast being launched this week, Chasing Ghosts: Murder at the Racecourse Hotel.

The podcast re-examines this cold case – the people involved, their lives, their times, their secrets and their deceits.

So who were they?

The murder victim

Fraser, born in Australia in 1892, was a big man, handy with his fists and quick in temper.

At age 20, he was accused of the indecent assault of a 15-year-old girl who had been chased by youths from the Greymouth railway sheds, where Fraser was working. He was acquitted at trial because the girl could not positively identify him.

He had to leave his railways job after a separate bullying incident, and worked for years in drapery, moving frequently from town to town.

But after entering the hotel trade in 1927, he quickly prospered to become what the tabloid press called "the sporting publican", the owner of a champion thoroughbred and the licensee of the Racecourse Hotel.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the hotel was awash with money. Gold sovereigns were found in the pockets of Donald’s trousers and a large amount of cash was discovered hidden in a linen press.

If you were a punter who liked booze, female company and a spot of illegal gambling, the hotel was a good place to go.

Fraser, though, was not a popular man. He was violent towards hotel patrons who annoyed him, giving them a hiding and throwing them off the premises over trifling disputes.

Police investigating the murder tracked down numerous men who had fallen foul of Fraser, sometimes years before. None of them became a suspect for killing him.

The publican’s wife

Fraser’s wife is central to the story. They had been married for 18 years and had two children.

Elizabeth enjoyed being a publican’s wife. It gave her plentiful access to the things she loved – alcohol, fine clothes, and cash. Especially cash. A detective said she worshipped money.

Could any one of them be the person who did the murder, in the bedroom, with the shotgun?

They all came under intense police scrutiny, and the police files which chart their comings and goings provide a fascinating glimpse into the lives, loves and hatreds of people frequenting a hotel on the edge of a New Zealand city in the 1930s.

An after-hours party

The files describe more details of that night before Fraser died, when he hosted one of his regular after-hours parties in the hotel.

This was the era of six o’clock closing – a measure introduced during World War I, requiring pubs to shut in the early evening, supposedly to maintain the efficiency of the workforce and encourage men to get home to their wives.

In fact, establishments such as the Racecourse Hotel might have closed their doors at 6pm, but drinking carried on in private, often with authorities turning a blind eye.

The police records note Fraser telling Ted Russell on one occasion to move his bicycle from the front of the hotel to the rear, to make it less obvious that after-hours drinkers were on the premises.

On the last night of his life, Fraser ordered champagne for his guests (making sure they paid their shares for it), spilled some on a woman’s dress, and got very, very drunk.

He wandered to the main staircase and sank down to sit on the third step. His wife and friends helped him upstairs to bed, where he passed out still partially clothed.

A shot in the night

Then, an hour or so after midnight, came the sound of an "explosion" in the Frasers’ bedroom, sending Elizabeth screaming into the hallway – or at least that was her story.

Joyce Fraser said the sound of her mother’s screaming invaded her dreams and also sent her out into the passageway.

The two women then ran to wake Higgs, the studmaster and only other adult living long-term in the hotel.

He had not heard the shotgun blast. His room was in a separate wing.

"Don’s been shot," Elizabeth told him.

Higgs donned his trousers and put in his false teeth before rushing to the bedroom to find Fraser on the floor with blood seeping out across the carpet.

Police converge

Over the following hours, all available police officers converged on the hotel. Witnesses later described them as arriving from all directions by car and bicycle. A pathologist, fingerprint expert and photographer were also called in.

The constables spread out, searching for the murder weapon, thinking the killer might have thrown it away as he fled the scene.

Detectives interviewed the hotel’s occupants and staff and trainers arriving for the day’s work at the nearby Riccarton Racecourse.

Believing the murderer may have left the area by car, they collated and examined reports of people driving about in the early morning – something that was still relatively uncommon in this era.

They tracked down, examined and ruled out every shotgun they could find within a 3km radius of the hotel.

But, despite this becoming one of the biggest investigations in South Island history to that date, days passed and neither the killer nor the murder weapon could be found.

The Murder Commission

Under pressure from the public, the press and the politicians, the New Zealand Police called in two highly-regarded sleuths from outside Christchurch – Detective Sergeants J.B. (Bruce) Young and Ernest (Tap) Jarrold.

The pair had history together, having joined forces in 1932 to solve the axe murder of Jim Flood in Picton – a case in which the victim’s shattered but wired-together skull had been presented, sensationally, as evidence in court.

Truth dubbed Young and Jarrold "the Murder Commission".

Their investigations were exhaustive, employing techniques that seem ahead of their time forensically.

For instance, they put fragments of the shotgun cartridge wad retrieved from Fraser’s corpse under a microscope. From the combination and colours of the fibres used, they established the cartridges had been manufactured by the Colonial Ammunition Company in Auckland between two specific dates earlier in 1933.

The two detectives travelled the length and breadth of the country to track down the sellers and end users of more than 140,000 shells.

They succeeded in accounting for all but about 50, two of which were used to kill Fraser.

Despite their wide-ranging thoroughness, the Murder Commission was also looking closer to home.

Particularly at Elizabeth Fraser, her apparent lack of concern following her husband’s death, the fact that she never asked them how the inquiry was going, and the lies she told them.

They began asking questions about Elizabeth, finding few people who had anything good to say about her and locating a cousin on the West Coast who said that nothing would convince him that she didn’t have a part to play in Donald’s death.

Jarrold and Young never thought Elizabeth shot her husband herself – there was no evidence she knew anything about guns, she would have had no way to dispose of the weapon, and there was no evidence such as powder marks on her or her clothing.

But they concluded that she did know who pulled the shotgun’s two triggers, meaning that she was implicated in Donald’s killing.

‘They will never find the gun’

This view was strengthened by an overheard remark, said to have been whispered by Elizabeth at Donald’s funeral.

"They will never find the gun," she supposedly said. "It is at the bottom of the sea. The gun is now in the fathoms of the sea."

If she wasn’t involved, how would she know that?

When the detectives tried to interview Elizabeth in January 1934, she refused to speak to them, becoming (in Young’s words) "white hot" with rage and calling in Christchurch’s best criminal barrister, Charlie Thomas.

Thomas went straight to the Commissioner of Police to get Young and Jarrold to back off.

Because of this, police had no opportunity to interrogate Elizabeth before the coronial inquest into Fraser’s death, held in open court in July 1934.

The inquest took on the appearance of a trial, with Elizabeth spending a grueling day and a half under cross-examination on the witness stand.

The coroner determined that Fraser had been murdered, and effectively destroyed Elizabeth’s reputation in the public eye by indicating that she – along with some of her inner circle – had lied to him on oath.

These lies are easy to detect. At the inquest, Elizabeth maintained that she and her husband were happy together and did not argue. This simply wasn’t true.

A ‘donnybrook’ upstairs

About three weeks before Fraser died, they had been involved in a violent row, during which Elizabeth took a pair of scissors to her husband’s suits, overcoat and fancy pyjamas.

When Higgs, overhearing the argument, mentioned to the hotel cook that there had been "a donnybrook upstairs", the cook responded that he had only heard the tail end of it.

The "donnybrook" was about the young, blonde Miss X - a Wellington woman whom Elizabeth had spotted with her husband at the Trentham racetrack after following him from Christchurch to Wellington when he took a trip away.

During that holiday and driving his wife’s car, Fraser took a road trip around the North Island, travelling with Miss X as husband and wife. Miss X’s real name was Eileen Hardcastle.

In his long, adoring love letters to her, transcribed into the police records, Donald had spoken of ending his marriage and even installing Eileen as the landlady of the hotel.

This was a double threat to Elizabeth – it would take away not only her husband, but the source of her livelihood, and the money she is said to have worshipped.

She would have had to leave the hotel and make her own way amid the economic and social uncertainties of the Great Depression.

After Fraser’s death, Elizabeth went on to form a relationship with a man named Charlie Chaney, who had worked at the racecourse and came to work for her at the hotel.

In 1935, they left for Australia together. Police followed her all the way to the ship they left on in Auckland, still trying to gain crucial information.

The Commissioner of Police wrote to his counterpart in New South Wales telling him that Elizabeth was not a suitable person to hold a hotel licence, effectively cutting her off from her most lucrative source of income.

She died in 1962, possibly taking with her the truth of what really happened to her husband - and any chance of police getting justice for him.

Justice not served

Even though the murder happened 90 years ago, it still matters that justice was not served following the killing.

In the words of Professor Katie Pickles, of the History Department at the University of Canterbury, who was interviewed for the podcast, putting right past wrongs is "a good and important question – It’s the question of our times".

"If we think that we’re a nation that’s all about redress and rethinking and remembering, there is that that interests us as historians," she said.

"But in this case, it’s about justice for the family, and justice for Donald," she said.

"It gives you a window, a view, into society at the time and what it was like. And it brings it alive. It definitely brings alive what happened at the Racecourse Hotel."

Listen to Chasing Ghosts - Murder at the Racecourse Hotel to hear more about the evidence in the hunt for Donald Fraser’s killer.