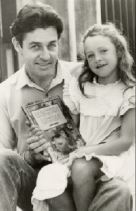

Gavin Bishop knew he wanted to be an artist when he was four.

Seventy-two years on, more than 70 published books and countless national awards later, he is continuing to do just that.

Bishop was born in Invercargill, but moved to Christchurch to study at the Canterbury University School of Fine Arts and graduated with an honours degree in painting in 1976.

He then became an art teacher at Te Aratai College, formerly Linwood College, before moving to Christ’s College, when another art teacher suggested he write a book for children.

“It was kind of weird because it was just out of the blue that this person said this and it struck a chord with me,” Bishop said.

“I suddenly realised that was something I’d been thinking about doing for a really long time, but I had never got around to doing it.”

English publishing company Oxford University Press (OUP) expressed it was looking for material that had a “strong New Zealand flavour” and had representatives visit Wellington at the time.

Bishop liked the idea of this, as he hadn’t grown up reading New Zealand books.

“When I was a child all of the books I read came from England, Australia, America mainly. It was a very exciting proposal.”

So Bishop got in contact with OUP and made a start on his first book about a sheep, as sheep farming was a major industry in the 1980s. He called it Bidibidi.

The second book Bishop wrote he set in Linwood, where he was still teaching, and even used the old Edmonds baking powder factory on Ferry Rd as one of the major buildings in the book. He called it Mrs McGinty and the Bizarre Plant.

Bishop said writing this book was “much more straightforward” as he began to get the hang of creating stories for children, and it was even published before Bidibidi.

Bishop continued to teach art, while working on his books at the same time, often in the school holidays and at night after dinner.

In 1998, he decided to pursue writing and illustrating books full-time. He remembers handing in his letter of resignation to the headmaster at Christ’s College.

“He rung me up and said ‘are you sure you want to do this’ and I said ‘yup’ and he said ‘would you like me to tear the letter up’ and I said ‘no, I’m really going to go ahead with this’.”

That year Bishop wrote a book called The House that Jack Built, which looked at the impacts of colonialism on New Zealand.

“It was very successful and in fact it’s being used still, in schools. That’s a book that’s been around for quite some time and looks as if it’s going to be still.”

Bishop recalls the moment he knew he wanted to be an artist at the age of four when a signwriter came to the small town of Kingston, south of Queenstown, where he lived.

The signwriter came to paint some signs outside the Kingston pub – which has since burnt down – and while he was there, he was asked to paint a big mural on the wall above the bar.

“I used to stand watching him paint this big scene of the lake up on the wall and I found that absolutely magical,” he said.

“That’s when I think I thought, that’s what I want to do.”

Because Bishop was taller than most kids his age, lots of adults would tell him he should become a policeman.

“That’s all you had to be, you didn’t have to be fit or smart or clever or anything like that, you just had to be tall and I would say ‘I don’t want to be a policeman, I want to be an artist’.”

Bishop remembers the first time he saw his book on sale at the old Whitcoulls on Cashel St, which was demolished after the earthquakes.

“I can remember walking through there and seeing my first book for sale and they had a mountain of it, they had like a hundred or more copies all stacked up and stacked on the floor I think.”

He can’t remember if it was Bidibidi or Mrs McGinty and the Bizarre Plant, but he asked the shop assistant if they wanted him to sign the books.

“I sat down and spent ages signing these books, and what was wonderful was they all sold quite quickly and they had to get some more in,” he said.

Bishop works from his studio at his Cashmere home with his wife Vivien, who he met at art school. She was also an art teacher, for Avonside Girls’ High School.

When asked what she thought about his achievements he laughed and said he didn’t know.

“We don’t talk about it much, it’s just part of our lives.

“Sometimes I’ll grab her to look at my work and get her to tell me what she thinks is wrong with it,” he said.

Bishop and Vivien have three daughters and three grandchildren, who have all grown up reading his books.

On a couple of occasions his grandchildren have made suggestions for books they would like to read, which Bishop has carried out.

When his grandson George was four he asked Bishop why he hadn’t written a story about a digger.

“He said ‘well I think you should write a book about a digger because I’d like to read it’ and I thought ‘oh okay’,” Bishop said.

Soon after Bruiser was published, a book about an angry digger that becomes caring and sensitive towards the end of the story.

Bishop said when he first started authoring children’s books, he was keen to write his own stories about things he wanted to write about.

He has stories based off his Māori whakapapa and has rewritten old fairy tales. However, in recent years, he has been commissioned to write books by his publishers, which he said has been a new challenge.

His latest book is called E Hoa, with te reo Māori and English versions available. It is part of a series for very young children, which will be released on Wednesday.

The book aims at showing children how to talk about feelings through a friendship between a child and their dog.

Bishop tends to work on one book at a time, preferring to finish one concept before moving onto the next.

He said his work can become quite consuming and often has a hard time switching off from thinking about his books.

“I’m always working on it, it’s hard to let it go.”

Of the 70-plus books Bishop has created, several have been translated into different languages, mostly to other European languages, but recently he has had some translated into Asian languages.

Bruiser has been translated and sold in China, Taiwan and Korea and another book called Teddy One Eye, which is a disguised biography about his life seen through the eyes of his teddy bear, has been translated and sold in China.

“I don’t hear from anyone in China who has read it but the fact that it’s been reprinted a couple of times means that it’s obviously selling well enough,” he said.

Bishop believes a country is made up partly by its literature and arts, something he thinks New Zealanders tend to forget – instead, getting carried away with devotion to sport.

“I think in a hundred years time people will still know who Kiri Te Kanawa is and who Janet Frame was and who Joy Cowley was. They’ll still know those people because their work will still be speaking to the people in the future.”

When asked if he thought he would ever have more than 70 books published he admitted he just started and “sort of kept going”.

It never occurred to him how successful he would be, although it was “nice to be recognised” through various awards, he said.

He has recently been named a finalist in the Publishers Association of New Zealand 2022 awards for best children’s book, which will be announced in September. He has previously won two PANZ awards for the best use of illustration in a children’s book in 2000 and 2009.

When asked if retirement was approaching at the ripe old age of 76, he laughed and said he wouldn’t know what to do with himself if he stopped creating books.

“At the moment I’m managing to produce work that’s okay and I’ll keep going while I’m doing that. I mean it keeps me alive, it’s challenging and it’s interesting and I get to meet interesting people,” he said.

“Writing books for our children with stories about us is really important.”