That is the stark warning from a major new report assessing how insurers might be forced to confront New Zealand’s increasing exposure to rising seas, prompting calls for stronger government action before it is too late.

COULD YOU BE AFFECTED? EMAIL US |

Nationally, about 450,000 homes that currently sit within a kilometre of the coast are likely to be hit by a combination of sea-level rise and more frequent and intense storms under climate change.

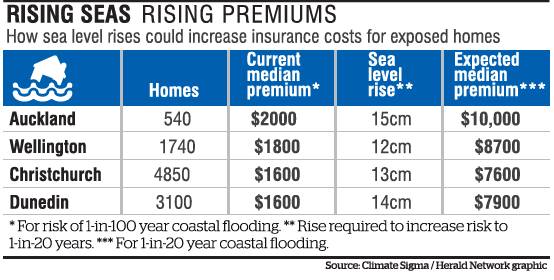

The report, published through the Government-funded Deep South Challenge, looked at the risk for around 10,000 homes in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin that lie in one-in-100-year coastal flood zones.

Premiums could leap from $1600 to $7600 and $7900, with 13cm and 14cm of sea-level rise respectively.

That risk is expected to increase quickly.

In Wellington, only another 10cm of sea-level rise — as is expected by 2040 — could push up the probability of a flood five-fold, making it a one-in-20-year event.

International experience and indications from New Zealand’s insurance industry suggest that companies start pulling out of insuring properties when disasters like floods become one-in-50-year events.

By the time that exposure has risen to one-in-20-year occurrences, the cost of insurance premiums and excesses will have climbed sharply, if insurance could be renewed at all.

The report found around 540 exposed homes in Auckland, with current median coastal flood premiums for once-in-a-century events of $2000, could reach that one-in-20-year threshold with just 15cm of sea-level rise.

If insurance was still available at that point, premiums would have soared to $10,000.

For the 1740 Wellington homes modelled, median premiums could jump from $1800 to $8700 with seas 12cm higher.

The research also suggested that just small increases in sea-level rise would likely cause at least partial retreat by insurers for the majority of those 10,000 homes, within only 15 years.

Insurance remained a requirement for residential mortgages, and failing to maintain them could trigger defaults.

While mortgages were often granted with repayment periods of up to 30 years in New Zealand, insurance contracts were renewed annually.

An insurer could exit a market within 12 months, while a lender could still have decades before their loans matured.

Despite rules requiring mortgagees to insure, a general absence of compliance checks meant banks did not know whether some properties they mortgaged remain insured beyond the first year of ownership.

Insurance Council of New Zealand chief executive Tim Grafton expected climate risks would continue to be signalled by insurers through means like price and excesses.

‘‘Insurers are likely to continue to cover existing homeowners in climate change or natural hazard-threatened areas, but we can expect premiums and excesses will increase,’’ Mr Grafton said.

“That might mean a flood plain property will have a $500 excess for fire damage but a $10,000 excess for flood damage.

“However, some companies might choose not to take on new customers in areas that have a known higher risk to sea-level rise and flooding in 15 to 20 years.’’

Insurers needed to work with customers to ensure they understood the reasons and costs that came with pricing certain risks, he said.

But all the while, homeowners were still choosing to buy, develop and renovate coastal property, and new houses were being built in climate-risky locations.

“People tend to be very good at ignoring low-probability events,’’ the report’s lead author, Dr Belinda Storey, of Climate Sigma, said.

“This has been noticed internationally, even when there is significant risk facing a property.

“Although these events, such as flooding, are devastating, the low probability makes people think they’re a long way off.’’

Dr Storey felt that market signals were not enough to effect change — and she said the Government could play more of a role around informing homeowners of risk.

Mr Grafton said the sector continued to push for adaptation measures and backed a recent recommendation for the Government to create a dedicated Climate Change and Managed Retreat Act.

“We also strongly advocate for local government to take a long view out 50 to 100 years and not to consent to developments in high-risk areas,’’ he said.

“The sooner we adapt to our changing climate, the less adaptation will cost us and the less we will be impacted by the increasing frequency and severity of storms.’’

Local Government New Zealand agreed clear adaptation legislation, guiding where people could live and build, would also help councils currently “stuck between a rock and sea-level rise’’.

“Certainty in the adaptation space would also help insurers, and make their business model more sustainable and less prone to sudden swings in risk pricing,’’a spokesperson said.

Climate Change Minister James Shaw said nationwide risk had been mapped out by an assessment published this year.

“Based on this, we are currently working on a national adaptation plan, which will set out how we plan to ensure communities are more resilient to the impacts of climate change.’’