In the first year Phil Smith mustered on the Soldiers Syndicate, the mustering team got snowed in at Blue Duck hut in the remote Otago back country.

It was so cold the men’s hobnail boots froze to the floor and icicles hung around the old tin hut.

"I just thought to myself, what the hell are we doing?" the then 21-year-old recalled.

He was following in the syndicate mustering boot-steps of his father Basil who used to comment that the huts on the syndicate weren’t much, but they were "a palace in a snowstorm".

The young Phil was never quite so convinced about the palace bit. "We got brighter with huts," he quipped.

The advent of more palatial digs several years later meant they no longer shivered as they lay in their bunks at night, as the snow blew under the iron, or came through the eaves, leaving the interior white.

Nor did they have to contend with thick smoke from the fireplaces which would force them out of the hut in the morning to clear their eyes before they started their beat.

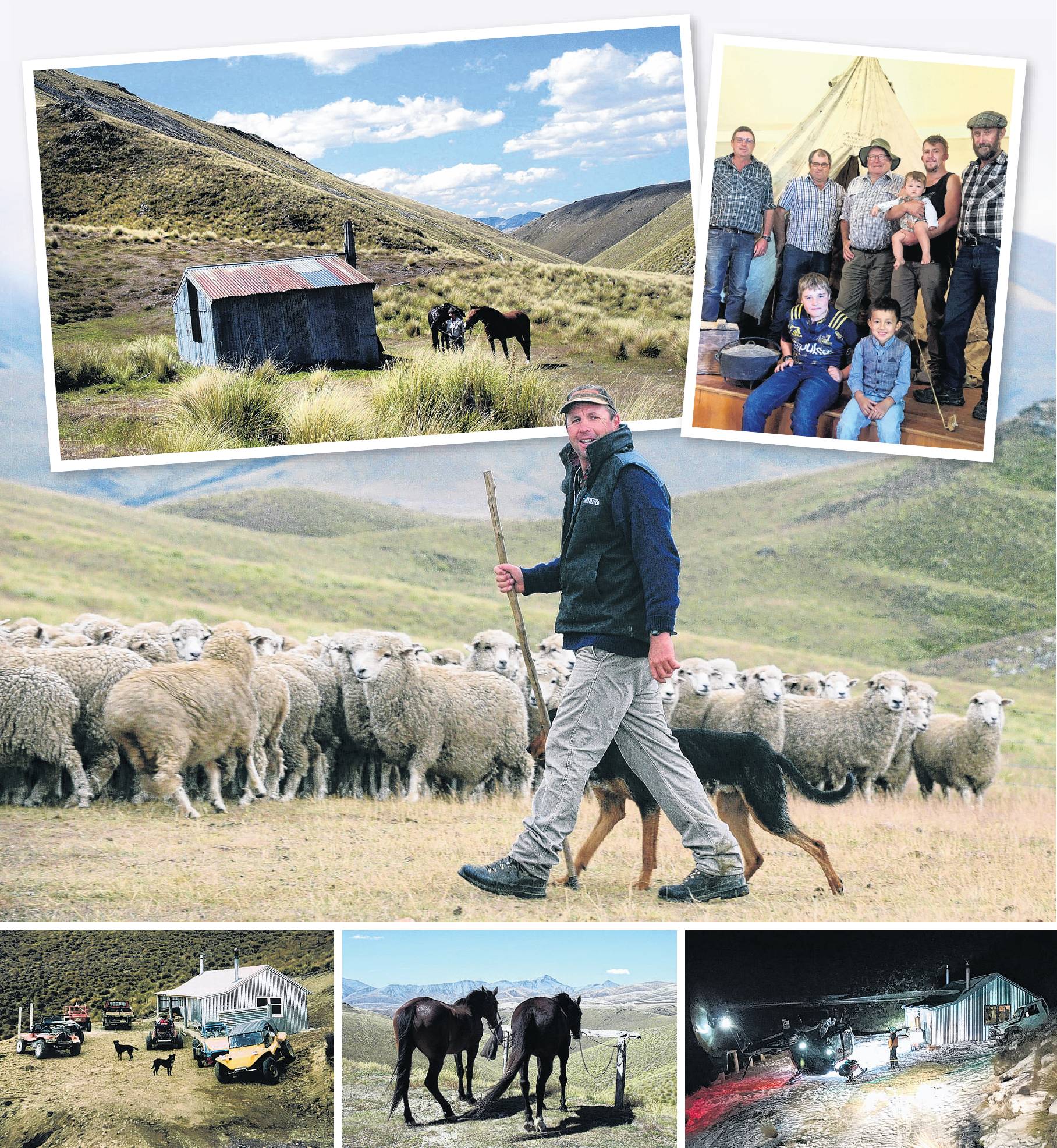

Every summer for the past 100 years, generations of Maniototo farming families have moved their sheep into the mountains to remove the pressure from their downland properties, in what has been a unique and annual ritual.

The Soldiers Syndicate’s origins came from the carving off of some of Kyeburn Station’s land when returned soldiers were given the opportunity to settle, through a ballot, in the aftermath of World War 1.

The successful applicants were Alex Maxwell, Alfred Carey, Charles Clouston Irvine, Patrick Daniel Hanrahan, William Edward Strode and James McMillan.

There was still a large tract of land, and it was suggested the successful applicants form a syndicate to make use of the area.

Over the ensuing years, shareholding has changed frequently and now only three families remain — the Smiths, Scotts and McAtamneys — who continue the pilgrimage to the Ida Range, with access from the Mt Buster Rd, 20km from Naseby.

The syndicate’s future has been uncertain at times.

In 2003, the Commissioner of Crown Lands decided to grant a special lease to the group on the expiry of a pastoral occupation licence.

Several years later, he changed his mind and decided to designate the land as a conservation area. The syndicate appealed to the High Court and, in 2008, the judge ruled in the farmers’ favour, but they are still waiting for that special lease to be drawn up.

Syndicate secretary-chairman Phil Smith recalled the court process as a "pretty horrendous time".

Juggling it with farm work, he spent much of his time heading to Christchurch to meet QCs and lawyers.

"It did consume us, it was bloody horrific," he said.

It also came at a cost, which they estimated at more than $200,000 of their own money, but walking away from the land was something that was never raised.

"The three families said ‘we’ve got to win this’ — just for our history ... for our community, just for what was right.

"I’ve got a son at home now [18-year-old Doug], he loves mustering and dogs. The generational thing is carrying on. If we lost it, then we lose it for him," he said.

"It’s part of Maniototo and Kyeburn’s history. This is conservation because it’s conserving history."

If the farmers brought sheep out of the syndicate in poor condition, then they would acknowledge that the country could not sustain the grazing.

But that was not the case, and stock were the best monitors in that sort of country.

"It shows we’re doing things right."

Mr Smith had contacted the Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association and it appeared that while there had been other similar syndicates throughout New Zealand — including in the Patearoa area — they had virtually all disbanded.

Basil Smith died in February, 2017, aged 83, and his son was saddened that he never got to see the lease finalised.

"We’ll do that for him," Phil Smith said.

Fellow shareholder Jock Scott said he could not stress enough the importance of the summer country, as it relieved the pressure on stocking on down country farms.

Those involved in the syndicate had learned about working together to look after the land. There was a place for grazing and, while there was much talk about wilding pines, sheep were the first to "nip them off", Mr Scott said.

Often the stocking rate on the syndicate was below what they were allowed to stock, which was 6500 sheep for 12 weeks.

When the land was taken up there was also the opportunity for winter grazing, but that was terminated in the 1960s.

Dave McAtamney estimated the stocking rate on farms would have to be at least one-third — possibly half — if they did not have access to the syndicate country.

Such a reduction in stock numbers would have downstream widespread effects, including on the likes of shearing contractors, transport operators and stock firms, Mr Smith added.

He was humbled by the number of people attending the centennial celebrations this week, with more than 100 registrations.

A meet and greet was held at the Naseby Town Hall last night, followed by a four-wheel-drive trip through the syndicate today, including lunch at the Soldier’s Hilton hut and dinner at the Danseys Pass Hotel.

"It’s history. I’ve never been a big history buff, I always look forward [but] it just shows its importance to a lot of people, just how important this history is," Mr Smith said.

Much has changed about the syndicate musters over the past 100 years, but the fundamentals still remain: musterers, horses, dogs and sheep, set amid the spectacular backdrop of the tussock-swathed high country. And, as Phil Smith succinctly put it, a day on the hill was still the same.

But advances in technology meant the development of tracks and better huts. In the early years, it was tents and packhorses, including mules from Kyeburn Station.

The sheep had also improved dramatically, while hand-held radios in recent years had saved a lot of legwork — literally.

Dogs had also benefited from advances in technology; today, they got a big ride on the back of the truck. Gone were the days of going out to let the dogs off, to find them lying with their feet in the air.

Before the two original syndicate huts — Blue Duck and Long Promise — were built, a bell tent was used that was shared by both the Soldiers Syndicate and neighbouring Mt Ida Syndicate.

Eight or nine men slept with their feet towards the pole, the only way they could all fit in.

Long Promise was named because it had been promised for a long time, and Dave McAtamney’s son Geoff recalled once arriving at the hut to find a pig running out from underneath it.

Dave McAtamney slept on the bell tent, using it as a mattress, for a couple of seasons and it has since been looked after by Jock Scott and pitched on the stage of the Naseby Town Hall for the centennial celebrations.

Less than enamoured by camping in the old huts, Phil Smith — a builder by trade — his father Basil, Colin Watson and Johnny Mulholland went for a tour to suss out a location for a new hut.

Basil knew a flat spot where there was also water for dogs nearby so they went and had a look, along with several other options. Keen to move on it, Basil suggested taking the dozer out the next day.

Phil’s diary showed that it took 22 days — "every day was another load of gear" — and there were a few wry smiles when Calder Stewart kindly said it would deliver materials on-site for nothing. Once Mr Smith started to explain the hut’s exact location, they said they’d drop it at his house.

In March 1991, the Soldier’s Hilton was used for the first time and the spacious and comfortable hut — with a stunning view of the surrounding high country — was as far removed from its predecessors as you could get.

Building the hut was to make a huge difference to the syndicate musters. Musterers were far better looked-after; they were warm and could dry out any wet clothes, Mr McAtamney said.

For years, they were often scouting around a week before the muster as they were short, but now there was "a queue wanting to get out there", he said.

Tim Crutchley has been the longest-serving musterer at what would have been 40 years if it had not been for Covid-19 last year — and the others reckoned he was so fit, he would probably make 50.

He got a gold watch for 25 years — a fun initiative introduced by Phil Smith — and Dave McAtamney quipped they might have to buy him a grandfather clock when he marked the half-century.

Jim Hore, from Stonehenge, was next in line for one — his knowledge and experience had also been greatly welcomed — but he missed his watch last year thanks to Covid-19.

The shareholders had to complete that muster in their family bubbles and were not allowed to stay in the hut. It was probably the first year that it had not been done with a full crew, but they eventually got it done.

One thing that had made a big difference had been using the Hore family’s Stonehenge horses — "good horses made a hell of a lot of difference to the way we do it" — and they usually had five or six musterers on horseback and the rest on foot.

They still took a packer and meals were traditional, hearty fare. No longer was meat killed "on the run", to feed both the musterers and the dogs, with the guts thrown on the roof of the hut — where the rusting was evident — to stop the dogs from eating it.

Back in the days of the mule train, musterers were limited to six bottles of beer each so the mules did not get overloaded.

As Jock Scott explained, there was nothing nicer than a bottle of beer — regardless of whether warm or cold — after a big day on the hill.

There have been a few sticky situations; several years ago, musterer George Black slipped on ice outside the hut when he went to turn the generator off and hit his head. His fingers were squeezed with a pair of pliers but he had no feeling.

The Otago Regional Rescue Helicopter landed outside the hut and Geoff McAtamney recalled how he thought "the place was going to blow down". Mr Black was flown to the spinal unit at Burwood Hospital and fortunately recovered.

The slick service showed how far the rescue system had come; about 1989 or 1990, a musterer fell of a bluff but there was no communication to raise the alarm.

The packer Jim Tallentire drove about an hour and a-half to alert emergency services, but the 111 system was down.

Eventually, a helicopter was sent, but the wrong map was put in it and it was flying up and down the mountain range.

It was just on dark and a tussock was lit, which alerted the helicopter crew to the location. But thanks to the downdraft from the helicopter, they had to put the fire out first before they could tend to the patient.

During one early muster, an old Scottish musterer got heavily intoxicated on a bottle of whisky at Long Promise and became abusive.

He had previously been kicked off a station in Southland because he put a .303 bullet through the single men's quarters.

This time, he took exception to another musterer's nasal hair and got into a heated argument. After creating a ruckus, he was kicked out of the hut.

The next morning, the musterers woke to see smoke up and down the gully. The disgruntled — and cold — musterer, who was in his slippers and only lightly clad, had lit tussocks to keep himself warm.

Those involved in the syndicate acknowledged that it was difficult to explain to those not familiar with it, just what it was like to be involved with.

"A lot of people don’t realise what it means to us," Mr Scott said.

And, as Jim Hore had said, you needed to be a "hutty person" to enjoy it.

"You’re in a totally different world," Mr Scott said.

Geoff McAtamney, who did his first muster when he was 17 — "I thought my feet were going to fall off" — reckoned reaching 100 years was a "pretty bloody spectacular achievement — phenomenal to be fair".

"So bring on the next 100," he said.