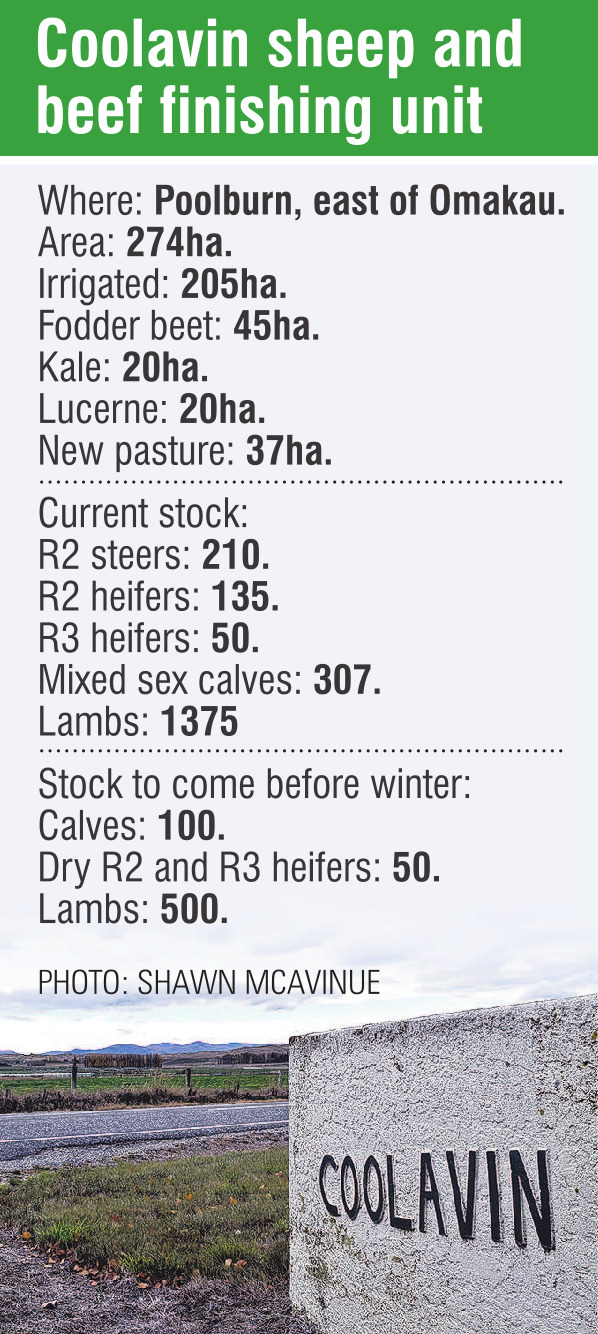

A sheep and beef finishing unit is developing in Central Otago. Equity partners Lloyd Brenssell and Richard Copland talk about the successes and challenges of pooling their capital and skills to grow a business at a field day on Coolavin farm in Poolburn last week. Shawn McAvinue was there.

The learning curve has been steep since Richard Copland and his family made a move north to develop a sheep and beef finishing unit in Central Otago.

"We had no idea what we were doing when we came and are learning as we go," Mr Copland said at a Beef + Lamb field day on the Poolburn farm last week.

Before moving to Poolburn, the Copland family lived near Gore.

Both he and his wife Renee had day jobs — his included stints working at PGG Wrightson and Rabobank.

At night, they worked on their family farm in Pukerau.

Juggling day jobs and a farm became trickier when they had children.

The couple wanted to ditch the day jobs and farm full-time.

As the family farm was too small to work on full-time, he searched for another way to realise the dream.

"I wanted something I could sink my teeth into."

The search led him to Fernvale Genetics owner Lloyd Brenssell in Moa Flat, West Otago.

A hunt began for a property featuring good soil and enough heat and water to finish cattle during winter to supply to market when prices were peaking.

The nearly 250ha farm Coolavin in Poolburn was bought more than two years ago to finish some cattle from Fernvale Genetics properties.

"We got a good feel for the potential of the block," Mr Copland said.

When they bought Coolavin it had two pivot irrigators and plans to allow them to install two more.

"The key to this property is its water quota — it has tonnes of water."

Another tick for Coolavin was it being north of Moa Flat.

Mr Copland believed stock finished better when moved north, rather than south.

Another benefit of farming in Poolburn was the number of empty stock trucks travelling past, making it cheaper to backload cattle to Coolavin.

A trading company was established to run an equity partnership.

Under the agreement, the Copland family own Coolavin and the partnership leases it and pays rent to the family.

The Brenssell family own 75% of all stock and small plant on Coolavin, such as sheep handling gear, and the Copland family "were working our way up to a quarter share".

The Brenssell family own 75% of all stock and small plant on Coolavin, such as sheep handling gear, and the Copland family ‘‘were working our way up to a quarter share’’. All of the bigger plant items, such as diggers, were owned by Mr Brenssell’s business, which contracted the work on Coolavin to the equity partnership.

‘‘We pay a full contracting rate,’’ Mr Copland said.

Mr Copland said the equity partnership had gone well so far but issued a warning for anyone considering being part of one.

‘‘They are easy to get into but potentially harder to get out of.’’

All parties should do their due diligence and make sure they could work together, Mr Copland said.

Mr Brenssell said a motivation for entering an equity partnership was to make his farm operation more flexible to deal with climate challenges.

Finishing rising 2-year-old cattle could be a challenge in late winter and early spring in West Otago.

‘‘Moa Flat sucks when it comes to that.’’

Mr Brenssell said he had tried many different ways to put weight on his cattle in those testing times.

‘‘We were doing all sorts of stuff and the best we could ever get to was 800g a day and we climb up into this country and we are doubling it.’’

Having access to Coolavin was a way to ‘‘seek a balance with Mother Nature’’.

If a farm system was centred on one area, then the climate had more of an impact on the operation.

Integrating a farm system in a different area allowed for four lambing and three calvings a season, spreading the risk of adverse weather hitting.

For his farm business to operate at its potential, Coolavin needed to be bigger, Mr Brenssell said.

‘‘We are working on that. It is a really good template but if it was two or three times bigger, you could really make it boogie.’’

Mr Copland said the development of Coolavin included redesigning the property and farm system for optimal production.

Part of the development was installing new cattle yards and a scale.

The plan was to send cattle which were 600kg or heavier to the works from the end of August or start of September, depending on where the schedule was at.

‘‘We will do a load or two loads a week until we run out.’’

More than 90% of cattle sent away in 2022 qualified for Alliance beef value-add programmes, Mr Copland said.

About 7% qualified for the Handpicked tier two programme, 53% for Handpicked tier one and 34% for the ‘‘bottom grade’’ AngusPure programme.

Those cattle had an average carcass weight of 298kg and had an average of 72 days of grazing on beet.

About the same percentage of the cattle sent away last year qualified for programmes but the split was different — 4% qualified for tier two, 47% for tier one and 42% for AngusPure. |

The cattle sent away last year had an average carcass weight of 326kg and had more time grazing on beet.

Despite this, both herds had similar average marble scores of about 1.85.

The marbling scores of cattle could be impacted by many factors over their lifespan, Mr Copland said. To chase higher marbling scores took a lot of management so meat processors needed to pay a premium to reward the risk, he said. If the rewards were not there, it might be more profitable to winter dairy cattle than big beef cattle, he said. A nice surprise on Coolavin was the growth rates of lambs. ‘‘Coming from down South, we underestimated how well lambs do up here.’’

Store lambs put on up to 340g a day for up to six weeks on Coolavin.

Any lambs introduced to the system were drenched and left in the yards for 24 hours so any parasite eggs dropped by the flock would remain in the yards and die.

To further reduce any potential worm burden, cattle grazed paddocks lambs had been in on Coolavin, he said.

As he owned Coolavin, he paid for the developments, which cost $9000 per hectare.

|

The development included building a dam to future-proof water supply if the current scheme allocation was cut back.

A development cost to ‘‘blow out’’ was the installation of 32km of fencing, Mr Copland said.

‘‘I could have spaced my posts out further and probably dropped a wire but I think we have a fence which is going to last a hell of a long time.’’

He admitted the development work had ‘‘gone over the top in places’’.

‘‘We took the approach we are only going to do it once. We will be here for a long time.’’

shawn.mcavinue@alliedpress.co.nz