Retired Lawrence nurse Kirsty Garner received the letters as an heirloom from her mother.

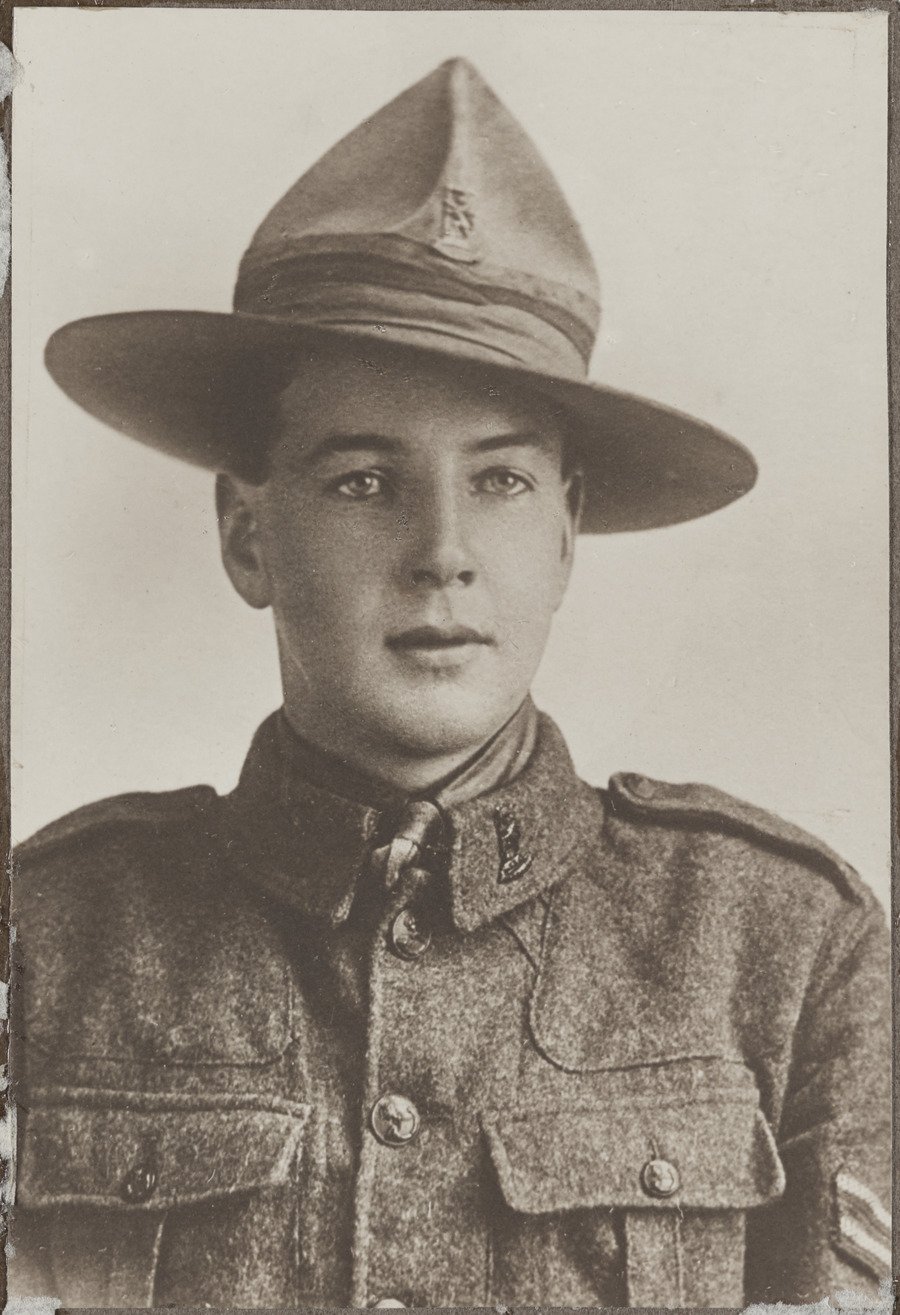

They were written to a younger brother by Mrs Garner’s uncle, WW1 New Zealand Rifle Brigade soldier Walter McIntyre, who enlisted age 20, and found himself amid the horrors of northern France.

In one letter, her uncle wrote, "Before we go any further, you take my advice and don’t come over until you have to. Hell isn’t worse, and I’ve never had such nightmares."

Mrs Garner said, nevertheless, he emerged as an able soldier.

After arriving in France in September, 1917, Walter earned a Military Medal for gallantry in the field. This led to a promotion to the rank of sergeant in 1918.

In 2024, on performing her yearly April ritual of reading the letters "while nibbling an Anzac biscuit", Mrs Garner was inspired to visit her uncle’s war grave and honour his sacrifices in person.

"Twelve months later, I was stepping off an aeroplane in Paris," she said.

"I had corresponded with Jacob Siermans of the new NZ Liberation Museum, Te Arawhata, in Le Quesnoy and he had agreed to meet me there, where Walter had spent his final days helping liberate the fortified town.

"I had thought he might be French, so I was very surprised, and pleased, when he greeted me with a perfect New Zealand accent."

Mr Siermans helped her find Walter’s grave in the nearby Fontaine-au-Bois Cemetery, and aided her attendance of Anzac Day ceremonies, she said.

"I had prepared translations of the waiata Purea Nei in te reo Māori, English and French, with help from Otago Girls’ High School.

"After singing the waiata, I knelt beside his grave and wept loud, unstoppable tears. I wept for myself, for my mother, her siblings and especially for my grandmother Louisa. Eighty years later, my aunty Mabs said she could still hear the agonised cry from Louisa when she received the telegram announcing Walter’s death."

Walter lost his life during one of the war’s more unusual — and honourable — battles, helping liberate Le Quesnoy with no loss of civilian life in November 1918.

Instead of opting to bombard the fortified town, New Zealand soldiers engineered a surrender of German troops through a surprise medieval siege strategy, scaling the walls by ladder.

Mrs Garner said the ingenious and humane method by which New Zealanders had liberated the town still resonated with locals today.

"I was greeted so warmly by everyone I met, particularly as a New Zealander.

"Walter was 22 when he died. By the time he reached the final post of his life, he had everything to live for, including a special young lady he had met in England.

"To stand by my Uncle Walter’s grave was one of the most profound experiences of my life."