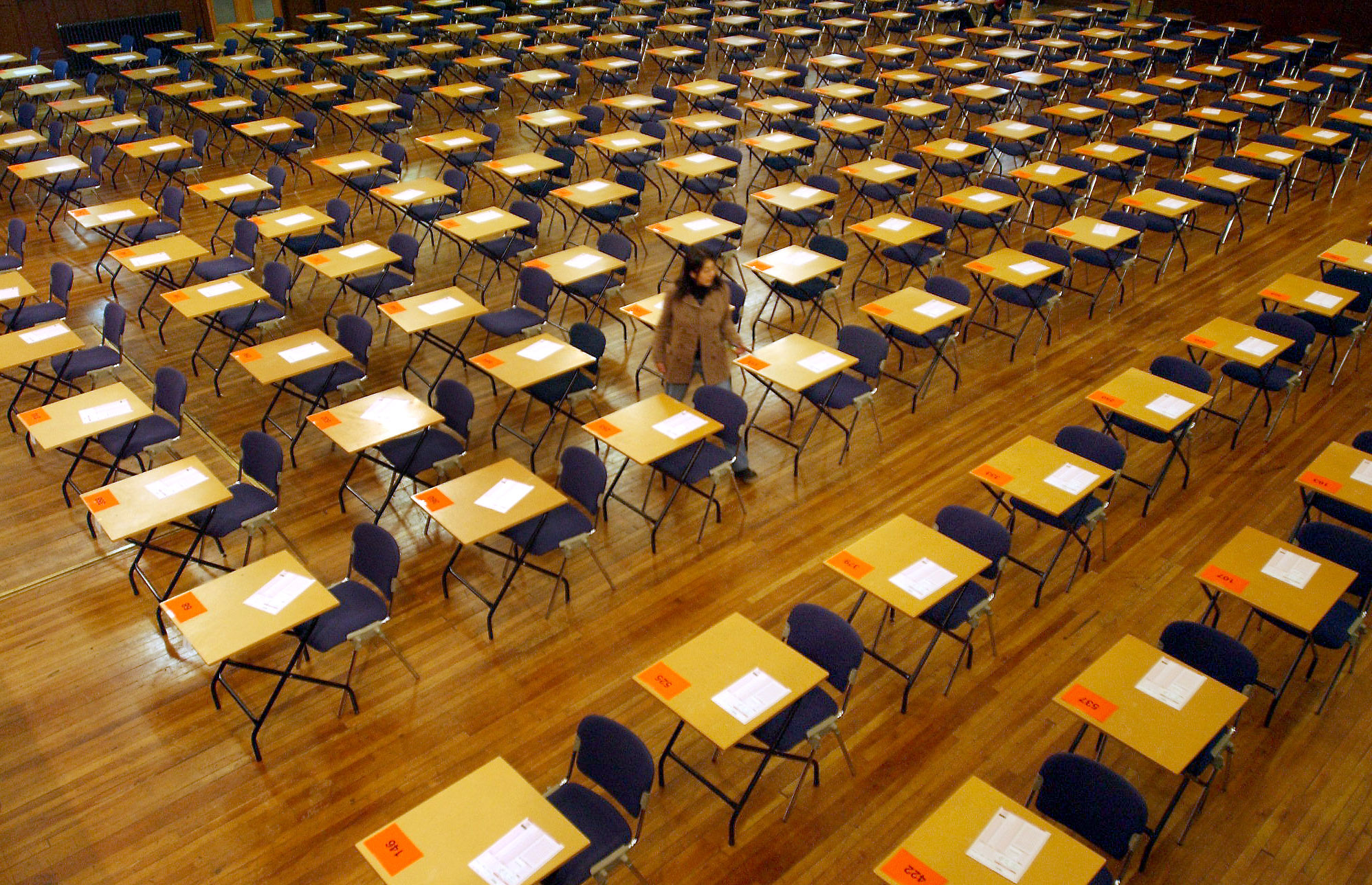

Many people still imagine medical school as endless lectures, anatomy labs, and late-night cramming. In reality, that image is as outdated as leeches and handwritten prescriptions.

Much has changed in the 150 years since the Dunedin School of Medicine opened, but some outdated assumptions still persist. Let’s tackle a few common myths:

■ "It’s all lectures and labs."

Though that may have been true 50 years ago, today’s training integrates classroom learning with hands-on experience from day one. Half of the six-year medical degree is now spent in clinical workplaces, including hospitals, GP clinics, and rural health settings.

■ "Medical training stops after graduation".

A century ago, graduating doctors could walk into general practice. Not any more. New Zealand medical graduates complete a two year-long internship before being fully registered. Most go on to train for another three to six years in a specialty such as general practice, paediatrics, or surgery.

Even then, learning doesn’t stop — doctors must keep up to date to renew their practising certificates.

■ "It’s a rigid hierarchy".

Though medicine retains some hierarchy, the modern doctor is just one member of a broader healthcare team. Medical schools now put much more emphasis on inter-professional education — learning with and from nurses, pharmacists, paramedics and others.

■ "The degree sets you up for life".

It is only the starting point. One former Harvard Medical School dean told his students: "Half of what we’ve taught you will be wrong in 10 years — and we don’t know which half." That’s why adaptability and lifelong learning are now core goals of medical training.

■ "Doctors always know best".

There’s growing recognition that patients are experts in their own lives. Modern doctors are trained to listen, partner, and collaborate — and to earn trust through ethical, patient-centred care.

■ "Good communication is something you’re born with".

Not so. Communication and professionalism are complex skills that must be taught, practised, and assessed — just like taking blood pressure or reading an X-ray.

■ "Bodies are machines, and doctors are mechanics".

This 1950s mindset is outdated. As people live longer with chronic conditions, the emphasis today is not just on curing disease, but on caring for the whole person and helping them live well.

■ "Illness is just an individual problem".

Today’s students learn about the social and environmental factors that shape health: housing, income, discrimination, family dynamics, and more. Understanding inequity is now central to becoming a good doctor.

Innovation at Otago hasn’t always been smooth — but when it works, the results can be transformative. A standout success story is the Rural Medical Immersion Programme, launched in 2007.

This fifth-year placement puts students into rural communities for an entire year, where they work alongside GPs and local health teams.

This model — a "longitudinal integrated clerkship" — gives students deep exposure to real patients and communities. It’s been shown to increase the likelihood of graduates choosing rural practice by six times.

Today, Otago students are placed in 57 locations across New Zealand, 48 of them rural or regional.

Even students who won’t go on to practise rurally benefit from understanding the challenges their rural colleagues face.

Otago has also been recognised internationally. It was only the fifth medical school in the world to receive the prestigious Aspire Award for excellence in medical education assessment — especially around professionalism. Its work in Hauora Māori and indigenous health, inter-professional education, and inclusive admissions has also received global praise.

If the past teaches us anything, it’s that medical education must be ready to evolve. The future won’t just be about what we teach, but how, where, and to whom.

Across 150 years of change, some qualities remain timeless: professionalism, empathy, clear communication, and critical thinking. The tools of the trade have evolved — from stethoscopes to scanning apps — but the purpose remains constant.

The role of the doctor is changing from lone expert to team player. Teachers are no longer gatekeepers of knowledge, but facilitators of learning. Students are encouraged to curate their own learning resources — drawing from a sea of information online and off.

Yet a tension remains. If medical education is increasingly personalised, how do we keep it grounded in collective care? We assess students as individuals, but doctors work in teams. We individualise education, but illness — and healing — are shared experiences.

So what does the future hold? Some parts of the medical school of tomorrow are already here. Otago’s commitment to diversity, rural health, and indigenous education is helping shape a workforce that better reflects — and serves — Aotearoa. Its reputation for assessment and professionalism is globally respected.

Its graduates are not only smart and skilled, but also ready to listen, collaborate, and grow.

The challenge now is to continue adapting — to new technologies, new health priorities, and new expectations from the public.

Ultimately, training doctors is about more than producing medical experts. It’s about shaping professionals who can walk alongside patients in times of vulnerability and complexity. Professionals who can adapt to change without losing sight of their values.

Medicine will keep changing. But our purpose must not. — Newsroom

■Tim Wilkinson is a professor of medicine and medical education at the University of Otago, Christchurch.