Why did you write this book?

Hospitals are some of the largest public buildings in New Zealand yet often their designers are not well known. Why is this?

I was particularly interested in how many designers based in provincial towns, who may have worked only in that area, were referred to as "architect to the [local hospital] board". They often developed deep institutional knowledge and goodwill, and were trusted to create relatively large, complex facilities. More recently, some practices have developed a specialty in health design and often work in co-operation with other New Zealand and international practices, so that a building’s authorship can become unclear.

Sometimes the designers are well known, but for other building types. For example, Frederick Thatcher, who designed the first public hospitals in Auckland and New Plymouth, is renowned for his timber Gothic Revival churches such as Old St Paul’s in Wellington.

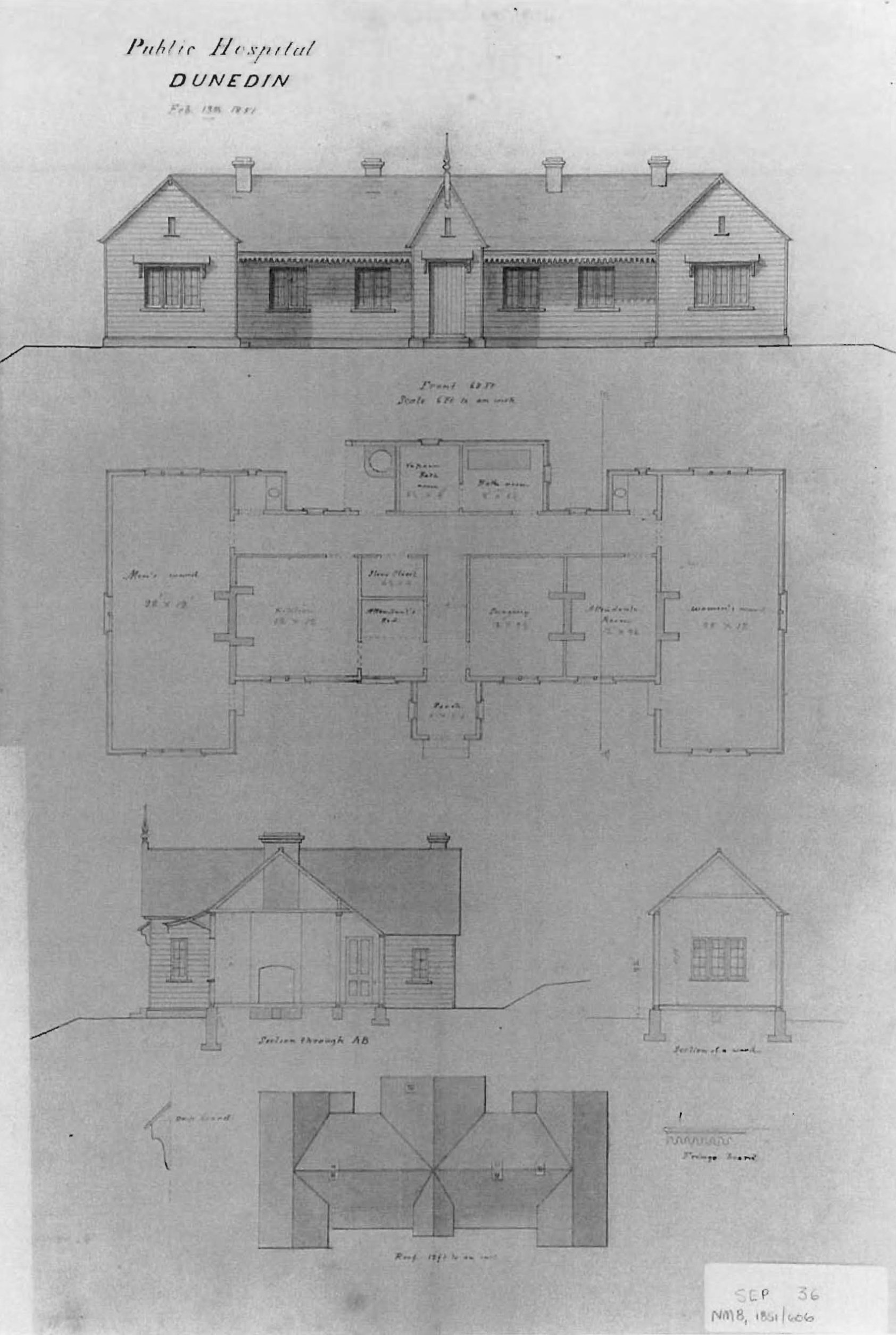

Mason & Wales is a highly regarded Dunedin-based firm, and the country’s oldest surviving architectural practice. William Mason designed the 1865 [South Seas] Exhibition building on the site of the current Dunedin Hospital, and the following year it was converted into patient accommodation, replacing the original hospital opened in the Octagon in 1851, on the site now occupied by the Municipal Building and town hall. The conversion was designed by provincial engineer John Turnbull Thompson, who had designed Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore and set out the original plan for Invercargill.

Which international hospital designs were adopted in New Zealand?

New Zealand architects followed international trends closely and were early adopters. With a small, widely dispersed population, however, many of our hospitals have been relatively limited in their scale. They have also tended to evolve incrementally as money became available and hence are often an amalgam of several different approaches and styles.

As medical technology developed, resulting in a greater variety of departments with their own specific space requirement, a more complex "bar" style concept developed but in New Zealand, hospitals evolved into this in a relatively ad hoc manner.

There were disagreements in the earlier 20th century as to whether hospitals should be larger facilities in major centres, or smaller facilities dispersed into rural areas — a debate that has resonances today. Small cottage hospitals opened across Canterbury in the 1920s, many of which were designed by Collins & Harman, which was continued by four generations of the Collins family for more than a century.

Two typologies became popular overseas in the later 20th century. Where land was available, "mat" layouts of informally placed low-rise buildings, separated by landscaped courtyards and often punctuated by one high-rise ward or office block, were popular. The new Gisborne Hospital, opened in 1985, is arguably New Zealand’s best example of this type.

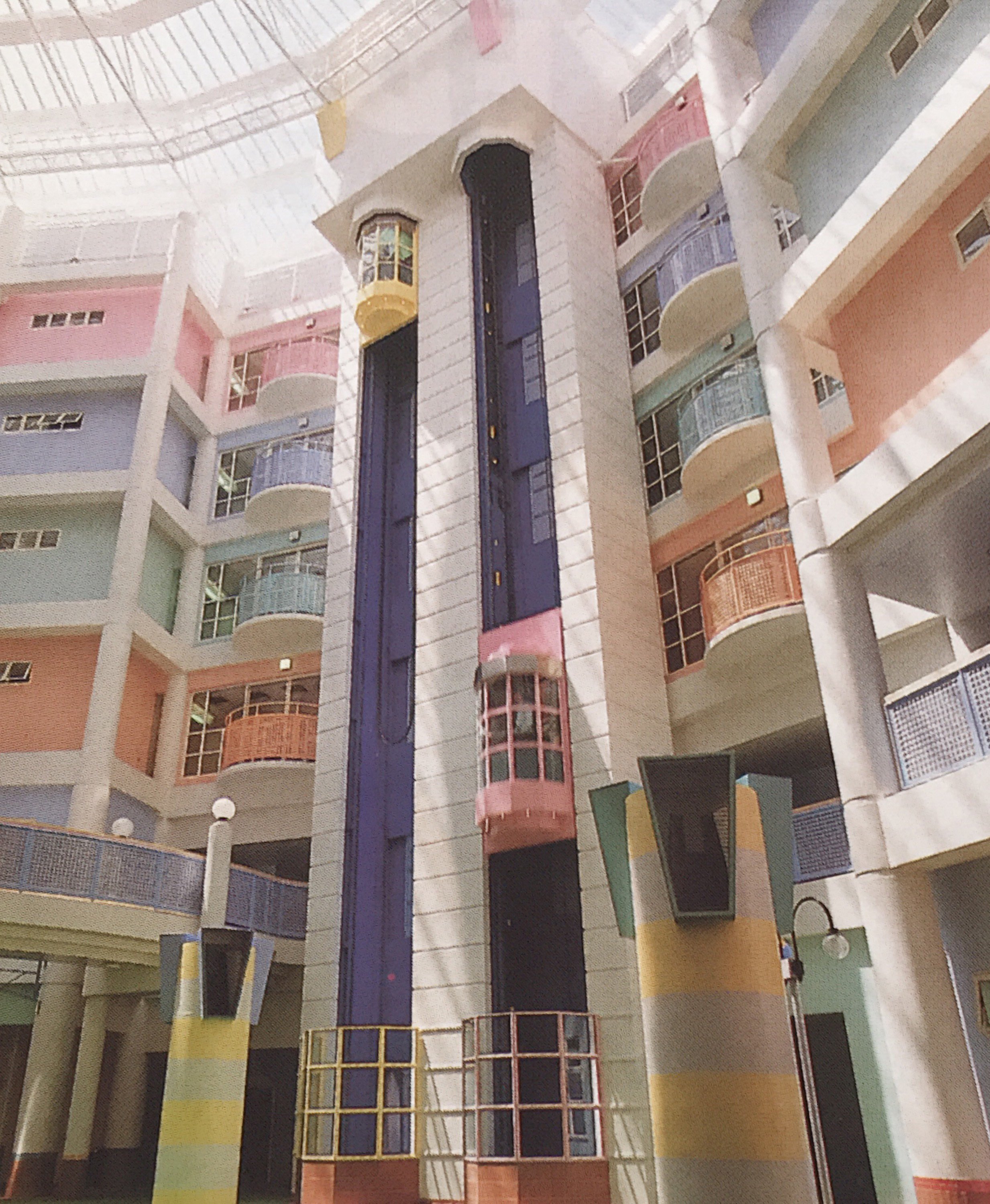

"Block" type designs — high-rise with deep floor plates — were necessary on tighter urban sites. These result in large areas of space with no natural light or outlook, which are heavily reliant on air conditioning and artificial lighting. Stephenson & Turner’s main block at Auckland Hospital is a good example of this typology.

Do you have a favourite hospital building in the Otago-Southland region?

I also admired Henry McDowell Smith’s Maniototo Hospital in Ranfurly, demolished in 2021, which Heritage New Zealand regarded as "a notable example of a rural 20th century hospital built in a modern style".

When Oamaru Hospital was moved to a more central site in 2000, the new building incorporated the 1875 Grammar School building, designed by Thomas Forrester — an excellent example of adaptive reuse by architect John McKenzie. The early work of his practice, Forrester & Lemon, in the town centre is well-known, but they are also thought to have designed the 1907 building at Oamaru’s "hospital on the hill", and Forrester, his son John Meggett Forrester, the latter’s business partner Ivan Steenson and his son Harry Steenson were responsible for most of the work on the site for the next half-century.

Can hospital design help with the healing process?

From a practical viewpoint, having the right services such as power and medical gases in the optimum locations can improve staff efficiency and reduce treatment times.

With changes in medical technology, hospitals risk being out of date before they’re even opened. How do architects ensure the buildings are adaptable?

What steps are likely to be taken to ensure that hospitals in the future respond to climate change and environmental concerns?

Hospitals are particularly challenging in this regard as they are heavy users of resources and energy, both in their construction and operation. By incorporating on-site energy generation, using photovoltaic solar panels for example, health facilities can reduce their net energy demand while improving their resilience to natural disasters. Their external envelope needs to be carefully considered, as glass and aluminium require large quantities of energy to produce, and windows create significant thermal bridges in the building envelope. Therefore, their size and location need to be carefully considered to ensure that outlook and natural light are optimised, while reducing material use in construction and minimising heat loss or gain during operation.

New Zealand has extensive forests, and timber has been extensively used in the construction of smaller-scale hospital buildings. Innovative ways are being developed to use it as the structure for larger-scale commercial and residential buildings, and these could be used in hospitals as well.

Water is becoming increasingly scarce, even in areas where it was once abundant, and consideration should be given to capture, treatment and reuse.

Health facilities generate significant quantities of waste, and this has increased significantly over recent years as items including personal protective equipment, medical implements, curtains and bedpans have been made disposable. This has certainly aided infection control, but we do need to consider other options.

Opritech installed New Zealand’s first modular operating theatre at Churchill Hospital in Blenheim in 2013.PHOTOS: SUPPLIED

What is your opinion of the design of the new Dunedin hospital?

Opritech installed New Zealand’s first modular operating theatre at Churchill Hospital in Blenheim in 2013.PHOTOS: SUPPLIED

What is your opinion of the design of the new Dunedin hospital?

I can only comment on what is publicly available. However, this will be a quantum change from the existing facility, much of which is more than 50 years old. It will be patient-centred and efficient, and anticipates the projected shift towards outpatient and community-based care. It also includes shell space to provide further patient beds in future without having to build a new structure or building envelope, which can be difficult and disruptive in an operating facility.

I understand that the aim is still to achieve a five-star Green Star rating, making this one of the country’s most sustainable hospital buildings.

One noticeable feature on the plans is the aim to have at least half the inpatient beds in single rooms with their own en suite. Research has shown that single rooms enhance infection control, patient privacy and dignity, and provide greater opportunities for whānau to stay and assist with caring. They do require more floor area per bed and hence are more expensive to build. The ratio of single rooms in New Zealand public hospitals has increased over time. However, in most new buildings for the last 25 years it has been around 25-30%, so this is a significant enhancement.

Some functions, such as oncology, will remain on the current site in the interim, however. Similarly, the hospital will not be immediately adjacent to the medical school. Over time, these may be reintegrated as required, as existing facilities reach the end of their life.

Hospitals have large numbers of staff and visiting public, and the new hospital is unique in New Zealand for its central location, being only two blocks from the Octagon. Hopefully, this will enhance surrounding activity, improving safety and security, and enable the use of public transport to be maximised.